There is something about having your product installed in over twenty billion instances all over the world and even out of the globe. In my case it helps me remain focused on and committed to working on the security aspects of curl. Ideally, we will never have our heartbleed moment.

Security is also a generally growing concern in the world around us and Open Source security perhaps especially so. This is one reason why NVD making things up is such a big problem.

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) has a global presence. They host and share information about security vulnerabilities. If you search for a CVE Id using your favorite search engine, it is likely that the first result you get is a link to NVD’s page with information about that specific CVE. They take it upon themselves to educate the world about security issues. A job that certainly is needed but also one that puts a responsibility and requirement on them to be accurate. When they get things wrong they help distributing misinformation. Misinformation makes people potentially draw the wrong conclusions or act in wrong, incomplete or exaggerated ways.

Low or Medium severity issues

There are well-known, recognized and reputable Open Source projects who by policy never issue CVEs for security vulnerabilities they rank severity low or medium. (I will not identify such projects here because it is not the point of this post.)

Such a policy successfully avoids the risk that NVD will greatly inflate their issues since they can already only be high or critical. But is it helping the users and the ecosystem at large?

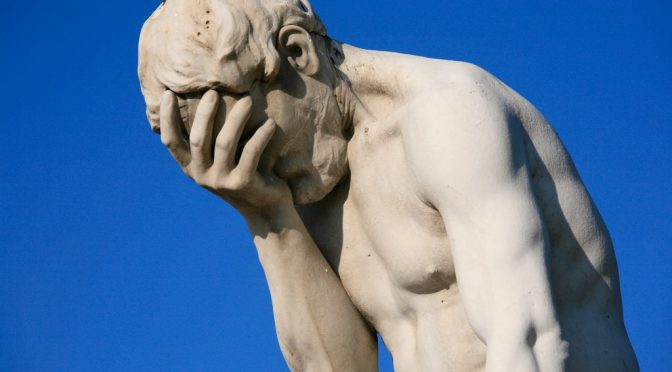

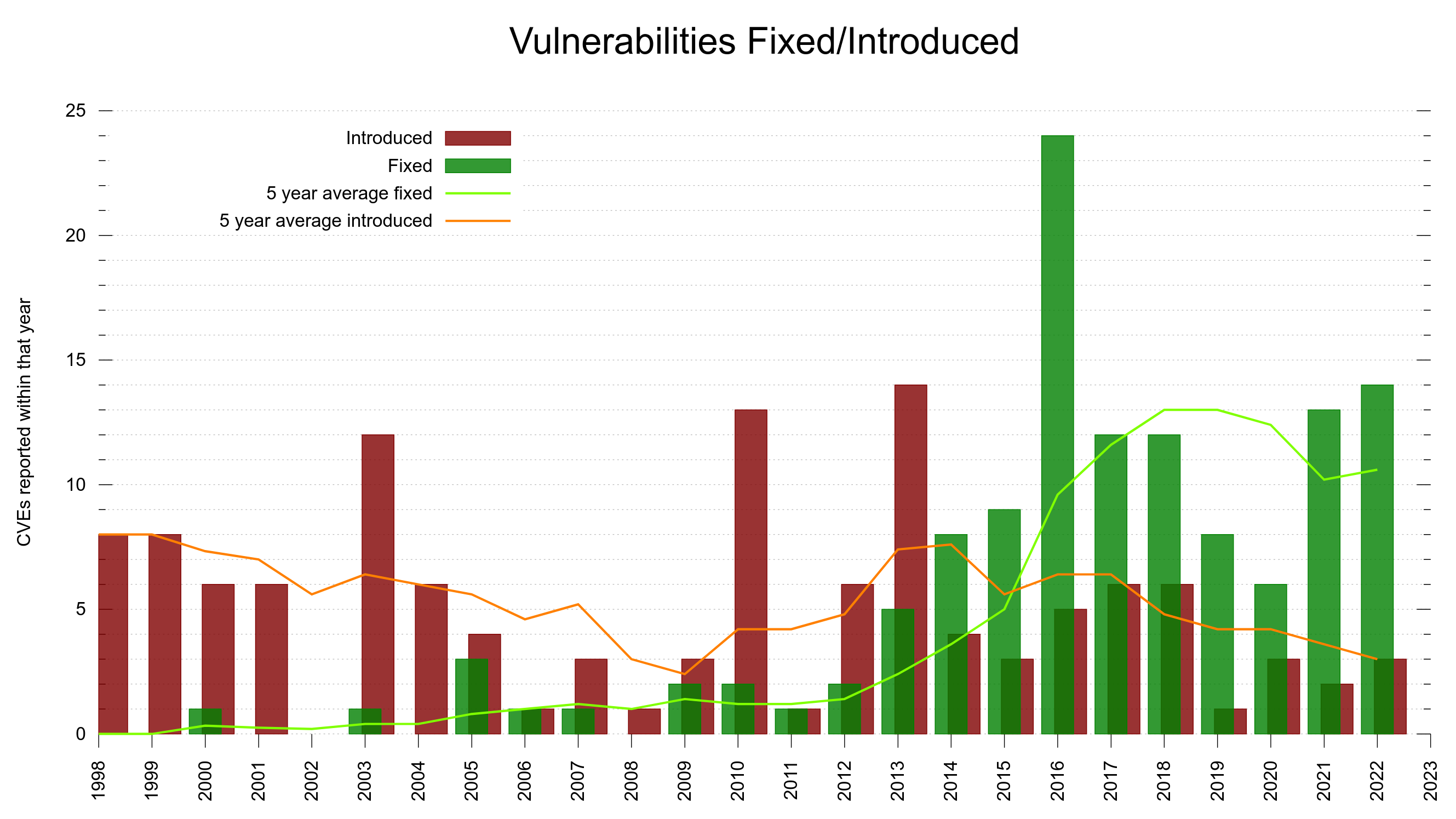

In the curl project we have a policy which makes us register a CVE for every single reported or self-detected problem that can have a security impact. Either at will or by mistake. This includes a fair amount of low and medium issues. The amount of low and medium issues as a total of all issues increases over time as we keep finding issues, but the really bad ones are less frequently reported.

As we have all data recorded and stored, we can visualize this development over time. Below is a graph showing the curl vulnerability and severity level trends since 2010.

Out of the 145 published curl security vulnerabilities so far, 28% have been rated severity high or critical while 104 of them were set low or medium by the curl security team.

I think this trend is easy to explain. It is because of two separate developments:

- We as a project have matured and have learned over time how to test better, write code better to minimize risk and we have existed for a while to have a series of truly bad flaws already found (and fixed). We make less serious bugs these days.

- Since 2010, lots of more people look for security problems and these days we are much better better at identifying problems as security related and we have better tools, while for a few years ago the same problem would just have become “a bug fix”.

Deciding severity

When a security problem is reported to curl, the curl security team and the reporter collaborate. First to make sure we understand the full width of the problem and its security impact. What can happen and what is required for that badness to trigger? Further, we assess what the likeliness that this can be done on purpose or by mistake and how common those situations and required configurations might be. We know curl, we know the code but we also often go back and double-check exactly what the documentation says and promises to better assess what users should be expected to know and do, and what is not expected from them etc. And we re-read the involved code again and again.

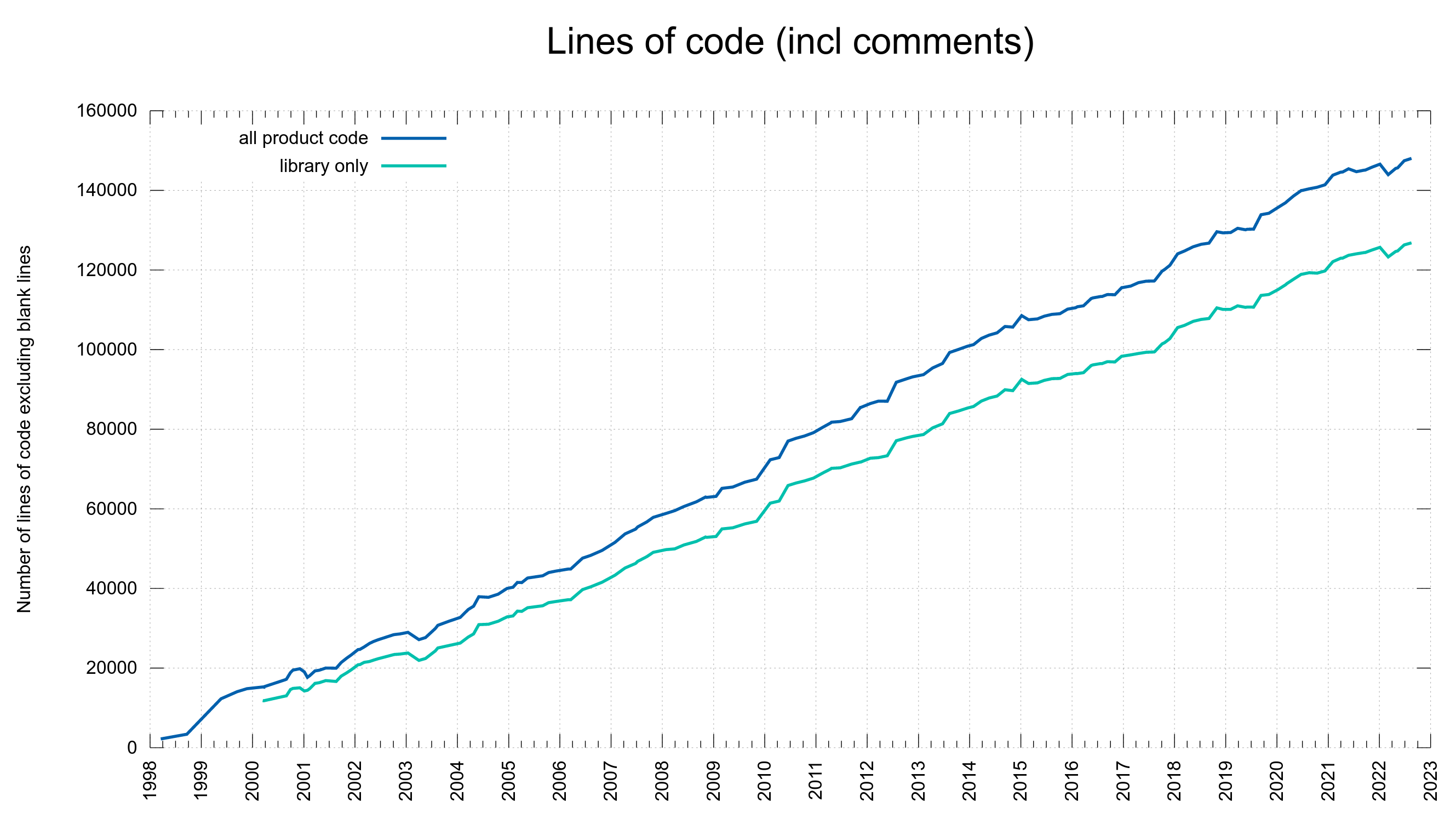

curl is currently a little over 160,000 lines of feature packed C code (excluding blank lines). It might not always be straight forward to a casual observer exactly how everything is glued together even if we try to also document internals to help you find deeper knowledge.

I think it is fair to say that it requires a certain amount of experience and time spent with the code to be able to fully understand a curl security issue and what impact it might have. I believe it is difficult or next to impossible for someone without knowledge about how it works to just casually read our security advisories and try to second-guess our assessments and instead make your own.

Yet this is exactly what NVD does. They don’t even ask us for help or for clarifications of anything. They think they can assess the severity of our problems without knowing curl nor fully understanding the reported issues.

A case to prove my point

In March 2023 we published a security advisory for the problem commonly referred to as CVE-2023-27536.

This is potentially a security problem, probably never hurts anyone and is in fact quite unlikely to ever cause a problem. But it might. So after deliberating we accepted it and ranked it severity low.

Bear with me here. I’ll spend two paragraphs revealing some details from the internal libcurl engine:

The problem is of a kind we have had several times in the past: curl has a connection pool and when a user makes a subsequent request which this particular option modified (compared to how it was when the previous connection was setup) it would wrongly reuse the first connection thinking they had the exact same properties.

The second would then accidentally get the wrong rights because it was setup differently. Still, the first connection would need the correct credentials and everything and so would the second one, it would just differ depending on what “GSSAPI delegation” that is allowed.

NVD ranks this

The person or team at NVD whose job it is to make up stuff for security vulnerabilities ranked this as CRITICAL 9.8. Almost as bad as it gets apparently. 10 is the max as you might recall.

When realizing this, at the end of May, I first fell off my chair in shock by this insanity, but after a quick recovery I emailed them (again) and complained (yet again) on setting this severity for *27536. I used the word “ridiculous” in my email to describe their actions. Why and who benefits from them scaremongering the world like this? It makes no sense. On the contrary, this is bad for everyone.

As a reaction to my complaint, someone at NVD went back and agreed to revise the CVSS string they had set and suddenly it was “only” ranked HIGH 7.2. I say “someone” because they never communicate with names and never sign the emails which whomever I talk to. They are just “NVD”.

I objected to their new CVSS string as well. It is just not a high severity security problem!

In my new argument I changed two particular details in the CVSS string (compared to the one they insisted was good) and presented arguments for that. For your pleasure, I include my exact wording below. (Some emphasis is added here for display purposes.)

How I motivated a downgrade

I could possibly live with: AV:N/AC:H/PR:H/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:N/A:N (4.4) - even if that means Medium and we argue Low. These are two changes and my motivations: Attack complexity high - because how this requires that you actually have a working first communication and then do a second is slightly changed and you would expect the second to be different but in reality it accidentally reuse the first connection and therefore gives different/elevated rights. It is a super-niche and almost impossible attack and there has been no report ever of anyone having suffered from this or even the existence of an application that actually would enable it to happen. It is more likely to only happen by mistake by an application, but it also seems unlikely to ever be used by an application in a way that would trigger it since having the same user credentials with different values for GSS delegation and assume different access levels seems … weird. This almost impossible chance of occurring is the primary reason we think this is a Low severity. With CVSS, it seems impossible to reach Low. Privileges Required high - because the only way you can trigger this flaw is by having full privileges for the *same* user credentials that is later used again but with changed GSS API delegation set. While the previous connection is still live in the connection pool. It would also only be an attack or a flaw if that second transfer actually assumes to have different access properties, which is probably debatable if users of the API would expect or not

CVSS still sucks

CVSS is a crap system so using this single-dimension number it seems next to impossible to actually get severity low report.

NVD wants “public sources”

NVD does not just take my word for how curl works. I mean, I only wrote a large chunk of it and am probably the single human that knows most about its internals and how it works. I also wrote the patch for this issue, I wrote the connection pool logic and I understand the problem exactly. Nope, just because I say so does not make it true.

My claims above about this issue can of course be verified by reading the publicly available source code and you can run tests to reproduce my claims. Not to mention that the functionality in question is documented.

But no.

They decided to agree to one of my proposed changes, which further downgraded the severity to MEDIUM 5.9. Quite far away from their initial stance. I think it is at least a partial victory.

For the second change to the CVSS string I requested, they demand that I provide more information for them. In their words:

There is no publicly available information about the CVE that clarifies your statement so we must request clarification from you and additionally have this detail added to the HackerOne report or some other public interface for transparency purposes prior to making changes to the CVSS vector.

… which just emphasizes exactly what I have stated already in this post. They set a severity on this without understanding the issue, with no knowledge of the feature that gets this wrong and without clues about what is actually necessary to trigger this flaw in the first place.

For people intimately familiar with curl internals, we actually don’t have to spell out all these facts with excruciating details. We know how the connection pool works, how the reuse of connections should work and what it means when curl gets it wrong. We have also had several other issues in this areas in the past. (It is a tricky area to get right.)

But it does not make this CVE more than a Low severity issue.

Conclusion

This issue is now stuck at this MEDIUM 5.9 at NVD. Much less bad than where they started. Possibly Low or Medium does not make a huge difference out there in the world.

I think it is outrageous that I need to struggle and argue for such a big and renowned organization to do right. I can’t do this for every CVE we have reported because it takes serious time and energy, but at the same time I have zero expectation of them getting this right. I can only assume that they are equally lost and bad when assessing security problems in other projects as well.

A completely broken and worthless system. That people seem to actually use.

It is certainly tempting to join the projects that do not report Low or Medium issues at all. If we would stop doing that, at least NVD would not shout wolf and foolishly claim they are critical.

My response

That is a ridiculous request. I'm stating *verifiable facts* about the flaw and how curl is vulnerable to it. The publicly available information this is based on is the actual source code which is openly available. You can also verify my claims by running code and checking what happens and then you'd see that my statements match what the code does. The fact that you assess the severity of this (and other) CVE without understanding the basic facts of how it works and what the vulnerability is, just emphasizes how futile your work is: it does not work. If you do not even bother to figure these things out then of course you cannot set a sensible severity level or CVSS score. Now I understand your failures much better. We in the curl project's security team already know how curl works, we understand this vulnerability and we set the severity accordingly. We don't need to restate known facts. curl functionality is well documented and its source code has always been open and public. If you have questions after having read that, feel free to reach out to the curl security team and we can help you. You reach us at security@curl.se I recommend that you (NVD) always talk to us before you set CVSS scores for curl issues so that we can help guide you through them. I think that could make the world a better place and it would certainly benefit a world of curl users who trust the info you provide. / Daniel