Section 9.1.1 in RFC7540 explains how HTTP/2 clients can reuse connections. This is my lengthy way of explaining how this works in reality.

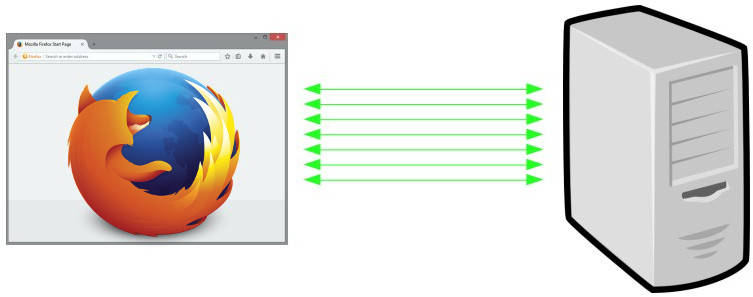

Many connections in HTTP/1

With HTTP/1.1, browsers are typically using 6 connections per origin (host name + port). They do this to overcome the problems in HTTP/1 and how it uses TCP – as each connection will do a fair amount of waiting. Plus each connection is slow at start and therefore limited to how much data you can get and send quickly, you multiply that data amount with each additional connection. This makes the browser get more data faster (than just using one connection).

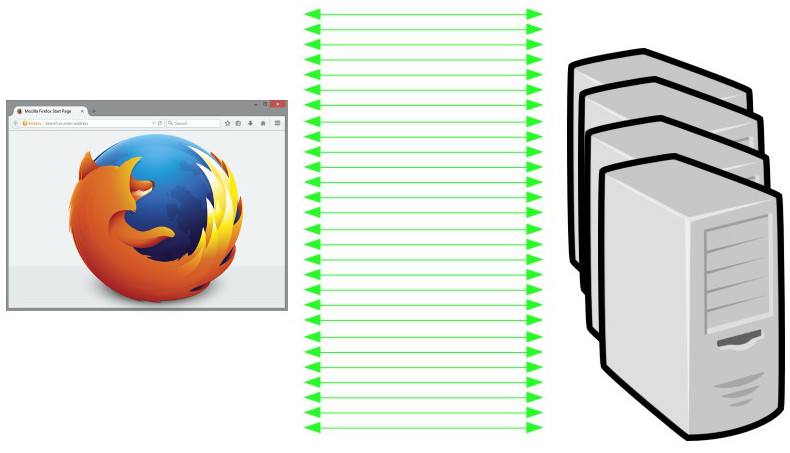

Add sharding

Web sites with many objects also regularly invent new host names to trigger browsers to use even more connections. A practice known as “sharding”. 6 connections for each name. So if you instead make your site use 4 host names you suddenly get 4 x 6 = 24 connections instead. Mostly all those host names resolve to the same IP address in the end anyway, or the same set of IP addresses. In reality, some sites use many more than just 4 host names.

The sad reality is that a very large percentage of connections used for HTTP/1.1 are only ever used for a single HTTP request, and a very large share of the connections made for HTTP/1 are so short-lived they actually never leave the slow start period before they’re killed off again. Not really ideal.

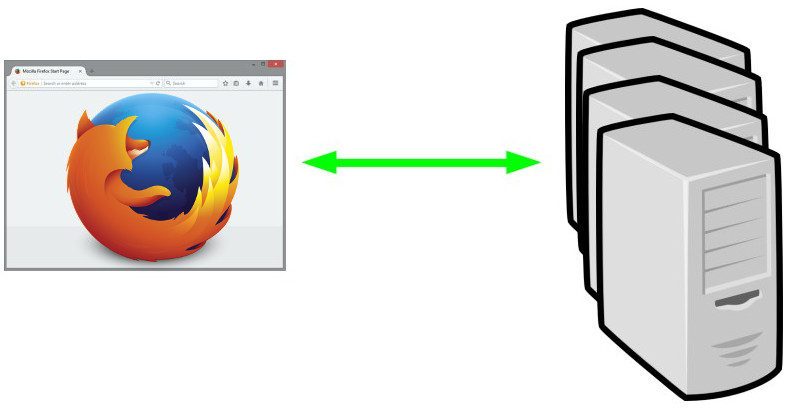

One connection in HTTP/2

With the introduction of HTTP/2, the HTTP clients of the world are going toward using a single TCP connection for each origin. The idea being that one connection is better in packet loss scenarios, it makes priorities/dependencies work and reusing that single connections for many more requests will be a net gain. And as you remember, HTTP/2 allows many logical streams in parallel over that single connection so the single connection doesn’t limit what the browsers can ask for.

Unsharding

The sites that created all those additional host names to make the HTTP/1 browsers use many connections now work against the HTTP/2 browsers’ desire to decrease the number of connections to a single one. Sites don’t want to switch back to using a single host name because that would be a significant architectural change and there are still a fair number of HTTP/1-only browsers still in use.

Enter “connection coalescing”, or “unsharding” as we sometimes like to call it. You won’t find either term used in RFC7540, as it merely describes this concept in terms of connection reuse.

Connection coalescing means that the browser tries to determine which of the remote hosts that it can reach over the same TCP connection. The different browsers have slightly different heuristics here and some don’t do it at all, but let me try to explain how they work – as far as I know and at this point in time.

Coalescing by example

Let’s say that this cool imaginary site “example.com” has two name entries in DNS: A.example.com and B.example.com. When resolving those names over DNS, the client gets a list of IP address back for each name. A list that very well may contain a mix of IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. One list for each name.

You must also remember that HTTP/2 is also only ever used over HTTPS by browsers, so for each origin speaking HTTP/2 there’s also a corresponding server certificate with a list of names or a wildcard pattern for which that server is authorized to respond for.

In our example we start out by connecting the browser to A. Let’s say resolving A returns the IPs 192.168.0.1 and 192.168.0.2 from DNS, so the browser goes on and connects to the first of those addresses, the one ending with “1”. The browser gets the server cert back in the TLS handshake and as a result of that, it also gets a list of host names the server can deal with: A.example.com and B.example.com. (it could also be a wildcard like “*.example.com”)

If the browser then wants to connect to B, it’ll resolve that host name too to a list of IPs. Let’s say 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3 here.

Host A: 192.168.0.1 and 192.168.0.2 Host B: 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3

Now hold it. Here it comes.

The Firefox way

Host A has two addresses, host B has two addresses. The lists of addresses are not the same, but there is an overlap – both lists contain 192.168.0.2. And the host A has already stated that it is authoritative for B as well. In this situation, Firefox will not make a second connect to host B. It will reuse the connection to host A and ask for host B’s content over that single shared connection. This is the most aggressive coalescing method in use.

The Chrome way

Chrome features a slightly less aggressive coalescing. In the example above, when the browser has connected to 192.168.0.1 for the first host name, Chrome will require that the IPs for host B contains that specific IP for it to reuse that connection. If the returned IPs for host B really are 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3, it clearly doesn’t contain 192.168.0.1 and so Chrome will create a new connection to host B.

Chrome will reuse the connection to host A if resolving host B returns a list that contains the specific IP of the connection host A is already using.

The Edge and Safari ways

They don’t do coalescing at all, so each host name will get its own single connection. Better than the 6 connections from HTTP/1 but for very sharded sites that means a lot of connections even in the HTTP/2 case.

curl also doesn’t coalesce anything (yet).

Surprises and a way to mitigate them

Given some comments in the Firefox bugzilla, the aggressive coalescing sometimes causes some surprises. Especially when you have for example one IPv6-only host A and a second host B with both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. Asking for data on host A can then still use IPv4 when it reuses a connection to B (assuming that host A covers host B in its cert).

In the rare case where a server gets a resource request for an authority (or scheme) it can’t serve, there’s a dedicated error code 421 in HTTP/2 that it can respond with and the browser can then go back and retry that request on another connection.

Starts out with 6 anyway

Before the browser knows that the server speaks HTTP/2, it may fire up 6 connection attempts so that it is prepared to get the remote site at full speed. Once it figures out that it doesn’t need all those connections, it will kill off the unnecessary unused ones and over time trickle down to one. Of course, on subsequent connections to the same origin the client may have the version information cached so that it doesn’t have to start off presuming HTTP/1.