The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is according to the Wikipedia description: “a protocol, hypermedia and file sharing peer-to-peer network for storing and sharing data in a distributed file system.”. It works a little like bittorrent and you typically access content on it using a very long hash in an ipfs:// URL. Like this:

ipfs://bafybeigagd5nmnn2iys2f3doro7ydrevyr2mzarwidgadawmamiteydbzi

HTTP Gateways

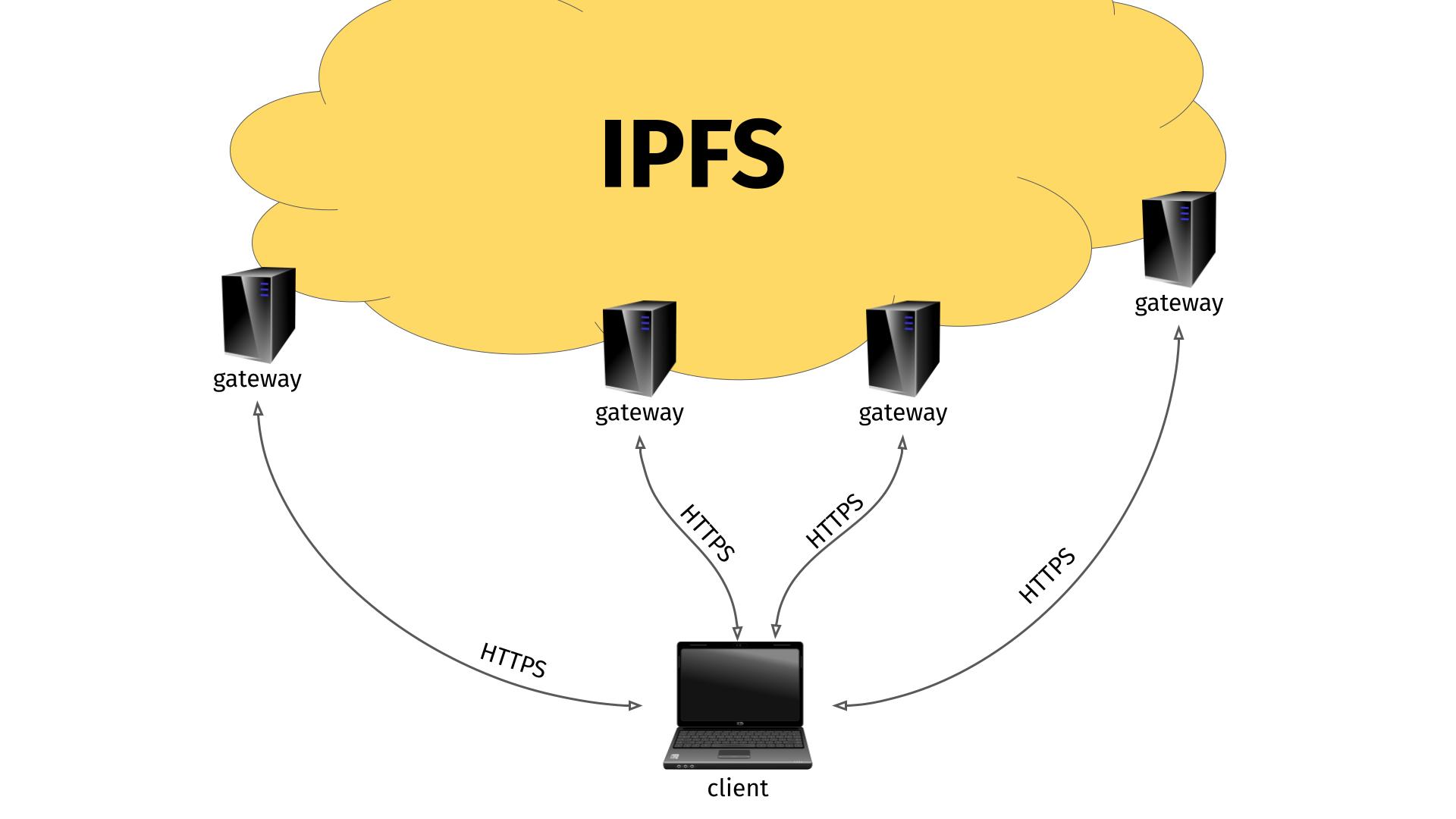

I guess partly because IPFS is a rather new protocol not widely supported by many clients yet, people came up with the concept of IPFS “gateways”. (Others might have called it a proxy, because that is what it really is.)

This gateway is an HTTP server that runs on a machine that also knows how to speak and access IPFS. By sending the right HTTP request to the gateway, that includes the IPFS hash you are interested in, the gateway can respond with the contents from the IPFS hash.

This way, you just need an ordinary HTTP client to access IPFS. I think it is pretty clever. But as always, the devil is in the details.

Rewrite ipfs:// into https://

The quest for IPFS aficionados have seemingly become to add support for IPFS using this gateway approach to multiple widely used applications that know how to speak HTTP(S). Just rewrite the URL internally from IPFS to HTTPS.

ffmpeg got “native” IPFS support this way, and there is ongoing work to implement the same kind of URL rewrite for curl. (into curl, not libcurl)

So far so good I guess.

The URL rewrite

The IPFS “URL rewrite” is done in such so that the example IPFS URL is converted into “https://$gateway/$hash”. The transfer is done by the client as if it was a plain old HTTPS transfer.

What if the gateway is not local?

This approach has its biggest benefit of course when you can actually use a remote IPFS gateway. I presume most random ordinary users who want to access IPFS does not actually want to download, install and run an IPFS gateway on their machine to use this new power. They might very well appreciate the idea and convenience of accessing a remote IPFS gateway.

After all, the gateways are using HTTPS so at least the transfers are secure, right?

Leading people behind IPFS are even running public IPFS gateways for anyone to use. Both dweb.link and ipfs.io have been mentioned and suggested for default use. Possibly they are the same physical host as they appear to have the same IP addresses (owned by Protocol Labs, one of the big proponents behind IPFS).

The IPFS project also provides a list of public gateways.

No gateway set, use a default!

In an attempt to make this even easier for users, ffmpeg is made to use a built-in default gateway if none is set by the user.

I would expect very few users to actually have an IPFS gateway set. And even fewer to actually specify a local one.

So, when users want to watch a video using ffmpeg and an ipfs:// URL what happens?

The gateway sees it all

The remote gateway, that is administered by someone, somewhere, gets to see the full incoming request, and all traffic (video, whatever) that is sent back to the client (ffmpeg in this example) goes via the gateway. Sure, the client accesses the gateway via HTTPS so nobody can tamper with the traffic along the way, but the gateway is in full control and can inspect and tamper with the data as much as it likes. And there is no way for the client to know or detect if it is happening.

I am not involved in ffmpeg, nor do I have any insights into how the discussions evolved and were done around this subject, but for curl I have put my foot down and said that we must not blindly use and trust any default remote gateway like this. I believe it is our responsibility to not lure users into this traffic-monitoring setup.

Make sure you trust the gateway you use.

The curl way

curl will probably output an error message if there was no gateway set when an ipfs:// URL is used, and inform the user that it needs a gateway set to function and probably also show a URL for a page that contains more information about what this means and how to specify a gateway.

Bouncing gateways!

During the work of making the IPFS support for curl (which I review and comment on, not written or authored myself) I have also learned that some of the IPFS gateways even do regular HTTP 30x redirects to bounce over the client to another gateway.

Meaning: not only do you use and rely a total rando’s gateway on the Internet for your traffic. That gateway might even, on its own discretion, redirect you over to another host. Possibly run somewhere else, monitored by a separate team.

I have insisted, in the PR for ipfs support to curl, that the IPFS URL handling code should not automatically follow such gateway redirects, as I believe that adds even more risk to the user so if a user wants to allow this operation, it should be opt-in.

Imagine rising use of this

I would imagine that the ones hosting a popular default gateway either becomes overloaded and slow, or they need to scale up. If they scale up, they risk to leak traffic even wider. Scaling up also makes the operation more expensive, leading to incentives to make money somehow to finance it. Will the cookie car in the form of a massive data trove perhaps then be used/sold?

Users of these gateways get no promises, no rights, no contracts.

Other IPFS privacy concerns

Brave, the browser, has actual native IPFS support (not using any gateway) and they have an informative page called How does IPFS Impact my Privacy?

Final verdict

I am not dissing the idea nor implementation of IPFS itself. I think using HTTP gateways to access IPFS is a good idea in general as it makes the network more accessible. It is just a fragile solution that easily misleads users to do things they maybe shouldn’t. So maybe a little too accessible?

Credits

Image by Hans Schwarzkopf from Pixaba

Follow-up

I poked the ffmpeg project over Twitter, there was immediate reaction and there is already a proposed patch for ffmpeg that removes the use of a default IPFS gateway. “it’s a security risk”