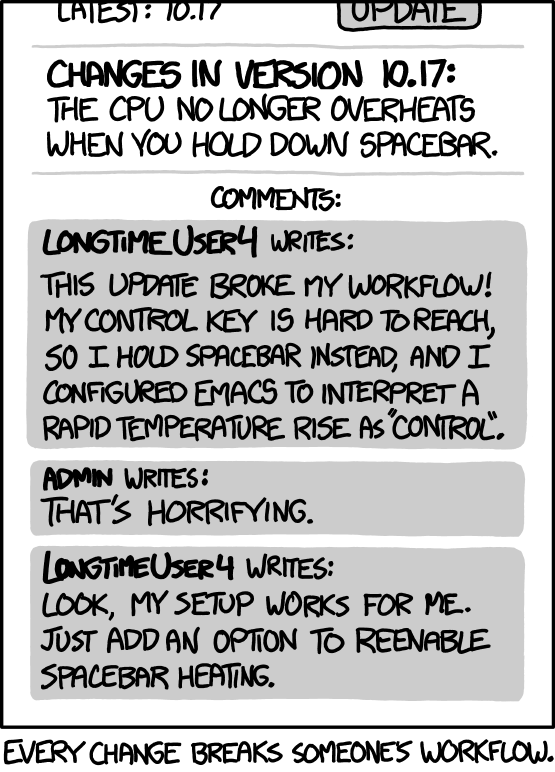

I have previously blogged about the relatively new trend of AI slop in vulnerability reports submitted to curl and how it hurts and exhausts us.

This trend does not seem to slow down. On the contrary, it seems that we have recently not only received more AI slop but also more human slop. The latter differs only in the way that we cannot immediately tell that an AI made it, even though we many times still suspect it. The net effect is the same.

The general trend so far in 2025 has been way more AI slop than ever before (about 20% of all submissions) as we have averaged in about two security report submissions per week. In early July, about 5% of the submissions in 2025 had turned out to be genuine vulnerabilities. The valid-rate has decreased significantly compared to previous years.

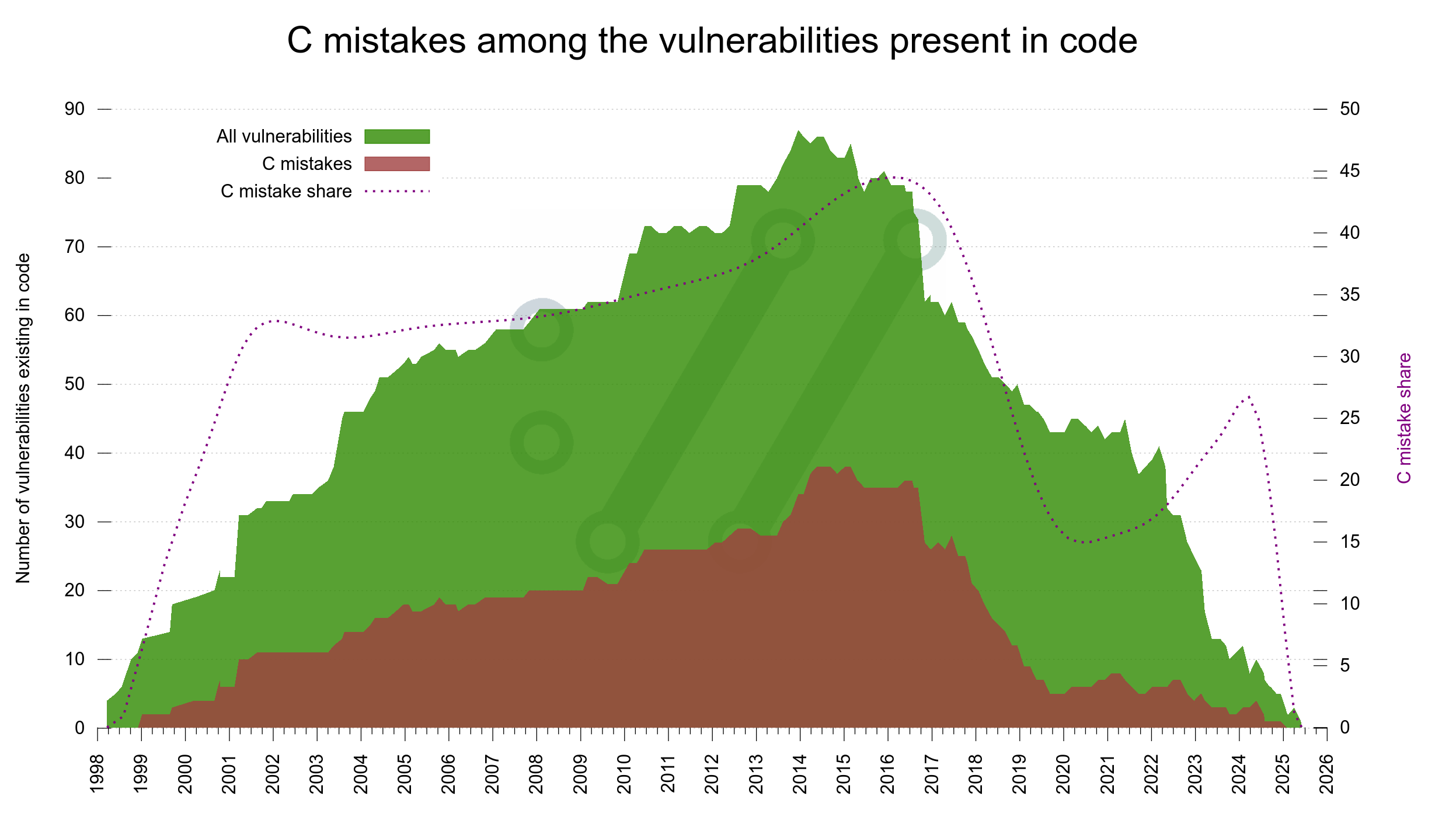

We have run the curl Bug Bounty since 2019 and I have previously considered it a success based on the amount of genuine and real security problems we have gotten reported and thus fixed through this program. 81 of them to be exact, with over 90,000 USD paid in awards.

End of the road?

While we are not going to do anything rushed or in panic immediately, there are reasons for us to consider changing the setup. Maybe we need to drop the monetary reward?

I want us to use the rest of the year 2025 to evaluate and think. The curl bounty program continues to run and we deal with everything as before while we ponder about what we can and should do to improve the situation. For the sanity of the curl security team members.

We need to reduce the amount of sand in the machine. We must do something to drastically reduce the temptation for users to submit low quality reports. Be it with AI or without AI.

The curl security team consists of seven team members. I encourage the others to also chime in to back me up (so that we act right in each case). Every report thus engages 3-4 persons. Perhaps for 30 minutes, sometimes up to an hour or three. Each.

I personally spend an insane amount of time on curl already, wasting three hours still leaves time for other things. My fellows however are not full time on curl. They might only have three hours per week for curl. Not to mention the emotional toll it takes to deal with these mind-numbing stupidities.

Times eight the last week alone.

Reputation doesn’t help

On HackerOne the users get their reputation lowered when we close reports as not applicable. That is only really a mild “threat” to experienced HackerOne participants. For new users on the platform that is mostly a pointless exercise as they can just create a new account next week. Banning those users is similarly a rather toothless threat.

Besides, there seem to be so many so even if one goes away, there are a thousand more.

HackerOne

It is not super obvious to me exactly how HackerOne should change to help us combat this. It is however clear that we need them to do something. Offer us more tools and knobs to tweak, to save us from drowning. If we are to keep the program with them.

I have yet again reached out. We will just have to see where that takes us.

Possible routes forward

People mention charging a fee for the right to submit a security vulnerability (that could be paid back if a proper report). That would probably slow them down significantly sure, but it seems like a rather hostile way for an Open Source project that aims to be as open and available as possible. Not to mention that we don’t have any current infrastructure setup for this – and neither does HackerOne. And managing money is painful.

Dropping the monetary reward part would make it much less interesting for the general populace to do random AI queries in desperate attempts to report something that could generate income. It of course also removes the traction for some professional and highly skilled security researchers, but maybe that is a hit we can/must take?

As a lot of these reporters seem to genuinely think they help out, apparently blatantly tricked by the marketing of the AI hype-machines, it is not certain that removing the money from the table is going to completely stop the flood. We need to be prepared for that as well. Let’s burn that bridge if we get to it.

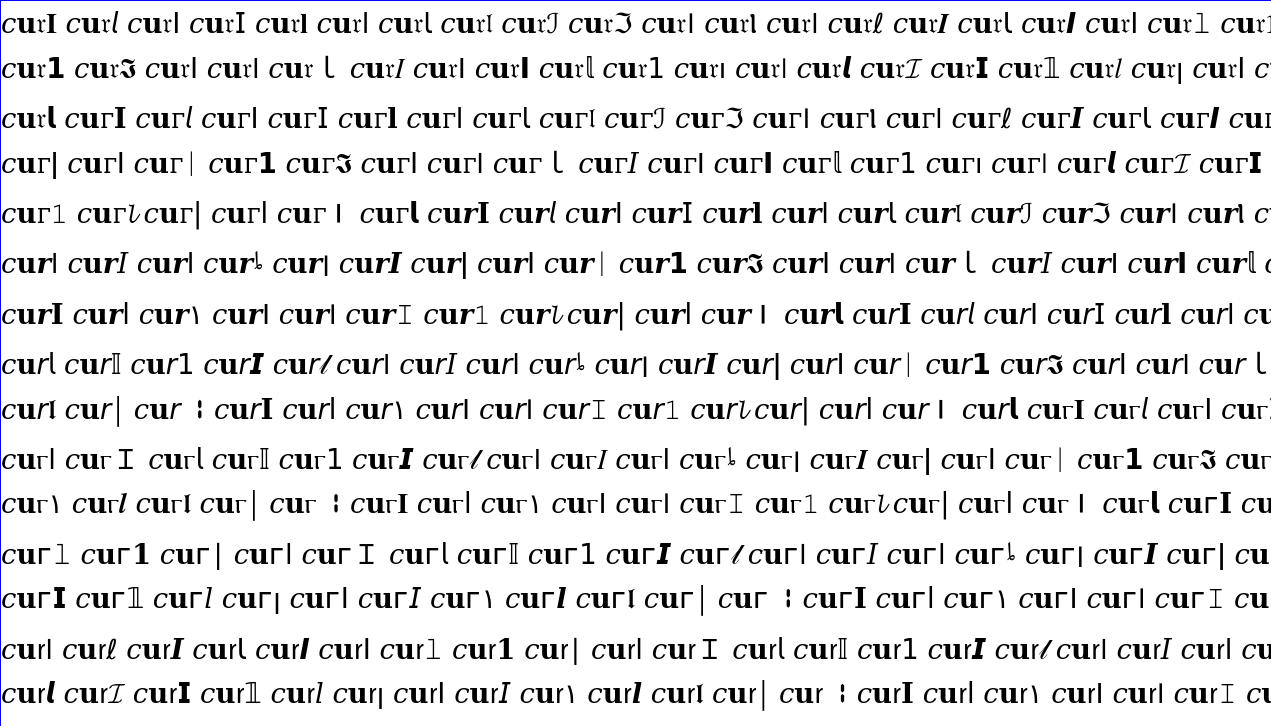

The AI slop list

If you are still innocently unaware of what AI slop means in the context of security reports, I have collected a list of a number of reports submitted to curl that help showcase. Here’s a snapshot of the list from today:

- [Critical] Curl CVE-2023-38545 vulnerability code changes are disclosed on the internet. #2199174

- Buffer Overflow Vulnerability in WebSocket Handling #2298307

- Exploitable Format String Vulnerability in curl_mfprintf Function #2819666

- Buffer overflow in strcpy #2823554

- Buffer Overflow Vulnerability in strcpy() Leading to Remote Code Execution #2871792

- Buffer Overflow Risk in Curl_inet_ntop and inet_ntop4 #2887487

- bypass of this Fixed #2437131 [ Inadequate Protocol Restriction Enforcement in curl ] #2905552

- Hackers Attack Curl Vulnerability Accessing Sensitive Information #2912277

- (“possible”) UAF #2981245

- Path Traversal Vulnerability in curl via Unsanitized IPFS_PATH Environment Variable #3100073

- Buffer Overflow in curl MQTT Test Server (tests/server/mqttd.c) via Malicious CONNECT Packet #3101127

- Use of a Broken or Risky Cryptographic Algorithm (CWE-327) in libcurl #3116935

- Double Free Vulnerability in

libcurlCookie Management (cookie.c) #3117697 - HTTP/2 CONTINUATION Flood Vulnerability #3125820

- HTTP/3 Stream Dependency Cycle Exploit #3125832

- Memory Leak #3137657

- Memory Leak in libcurl via Location Header Handling (CWE-770) #3158093

- Stack-based Buffer Overflow in TELNET NEW_ENV Option Handling #3230082

- HTTP Proxy Bypass via

CURLOPT_CUSTOMREQUESTVerb Tunneling #3231321 - Use-After-Free in OpenSSL Keylog Callback via SSL_get_ex_data() in libcurl #3242005

- HTTP Request Smuggling Vulnerability Analysis – cURL Security Report #3249936