For some reason, this post got picked up again and is debated today in 2021, almost 4 years since I wrote it. Some things have changed in the mean time and I might’ve phrased a few things differently if I had written this today. But still, what’s here below is what I wrote back then. Enjoy!

Every once in a while someone suggests to me that curl and libcurl would do better if rewritten in a “safe language”. Rust is one such alternative language commonly suggested. This happens especially often when we publish new security vulnerabilities. (Update: I think Rust is a fine language! This post and my stance here has nothing to do with what I think about Rust or other languages, safe or not.)

curl is written in C

The curl code guidelines mandate that we stick to using C89 for any code to be accepted into the repository. C89 (sometimes also called C90) – the oldest possible ANSI C standard. Ancient and conservative.

C is everywhere

This fact has made it possible for projects, companies and people to adopt curl into things using basically any known operating system and whatever CPU architecture you can think of (at least if it was 32bit or larger). No other programming language is as widespread and easily available for everything. This has made curl one of the most portable projects out there and is part of the explanation for curl’s success.

The curl project was also started in the 90s, even long before most of these alternative languages you’d suggest, existed. Heck, for a truly stable project it wouldn’t be responsible to go with a language that isn’t even old enough to start school yet.

Everyone knows C

Perhaps not necessarily true anymore, but at least the knowledge of C is very widespread, where as the current existing alternative languages for sure have more narrow audiences or amount of people that master them.

C is not a safe language

Does writing safe code in C require more carefulness and more “tricks” than writing the same code in a more modern language better designed to be “safe” ? Yes it does. But we’ve done most of that job already and maintaining that level isn’t as hard or troublesome.

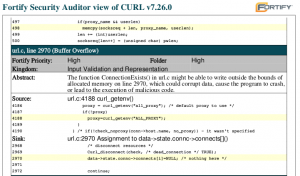

We keep scanning the curl code regularly with static code analyzers (we maintain a zero Coverity problems policy) and we run the test suite with valgrind and address sanitizers.

C is not the primary reason for our past vulnerabilities

There. The simple fact is that most of our past vulnerabilities happened because of logical mistakes in the code. Logical mistakes that aren’t really language bound and they would not be fixed simply by changing language.

Of course that leaves a share of problems that could’ve been avoided if we used another language. Buffer overflows, double frees and out of boundary reads etc, but the bulk of our security problems has not happened due to curl being written in C.

C is not a new dependency

It is easy for projects to add a dependency on a library that is written in C since that’s what operating systems and system libraries are written in, still today in 2017. That’s the default. Everyone can build and install such libraries and they’re used and people know how they work.

A library in another language will add that language (and compiler, and debugger and whatever dependencies a libcurl written in that language would need) as a new dependency to a large amount of projects that are themselves written in C or C++ today. Those projects would in many cases downright ignore and reject projects written in “an alternative language”.

curl sits in the boat

In the curl project we’re deliberately conservative and we stick to old standards, to remain a viable and reliable library for everyone. Right now and for the foreseeable future. Things that worked in curl 15 years ago still work like that today. The same way. Users can rely on curl. We stick around. We don’t knee-jerk react to modern trends. We sit still in the boat. We don’t rock it.

Rewriting means adding heaps of bugs

The plain fact, that also isn’t really about languages but is about plain old software engineering: translating or rewriting curl into a new language will introduce a lot of bugs. Bugs that we don’t have today.

Not to mention how rewriting would take a huge effort and a lot of time. That energy can instead today be spent on improving curl further.

What if

If I would start the project today, would I’ve picked another language? Maybe. Maybe not. If memory safety and related issues was the primary concern I had, then sure. But as I’ve mentioned above there are several others concerns too so it would really depend on my priorities.

Finally

At the end of the day the question that remains is: would we gain more than we would pay, and over which time frame? Who would gain and who would lose?

I’m sure that there will be or it may even already exist, curl and libcurl competitors and potent alternatives written in most of these new alternative languages. Some of them are absolutely really good and will get used and reach fame and glory. Some of them will be crap. Just like software always work. Let a thousand curl competitors bloom!

Will curl be rewritten at some point in the future? I won’t rule it out, but I find it unlikely. I find it even more unlikely that it will happen in the short term or within the next few years.

Discuss this post on Hacker news or Reddit!

Followup-post: Yes, C is unsafe, but…