At March 5 2013 we had another foss-sthlm meetup. The 12th one in fact, and out of the five talks during the event I spoke about curl and new technologies. Here are the slides from my talk:

Tag Archives: HTTP

The curl year 2012

So what did happen in the curl project during 2012?

First some basic stats

We shipped 6 releases with 199 identified bug fixes and some 40 other changes. That makes on average 33 bug fixes shipped every 61st day or a little over one bug fix done every second day. All this done with about 1000 commits to the git repository, which is roughly the same amount of git activity as 2010 and 2011. We merged commits from 72 different authors, which is a slight increase from the 62 in 2010 and 68 in 2011.

On our main development mailing list, the curl-library list, we now have 1300 subscribers and during 2012 it got about 3500 postings from almost 500 different From addresses. To no surprise, I posted by far the largest amount of mails there (847) with the number two poster being Günter Knauf who posted 151 times. Four more members posted more than 100 times: Steve Holme (145), Dan Fandrich (131), Marc Hoersken (130) and Yang Tse (107). Last year I sent 1175 mails to the same list…

Notable events

I’ve walked through the biggest changes and fixes and here are the particular ones I found stood out during this otherwise rather calm and laid back curl year. Possibly in a rough order of importance…

- We started the year with two security vulnerability announcements, regarding an SSL weakness and an injection flaw. They were reported in 2011 though and we didn’t get any further security alerts during 2012 which I think is good. Or a sign that nobody has been looking close enough…

- We got two interesting additions in the SSL backend department almost simultaneously. We got native Windows support with the use of the schannel subsystem and we got native Mac OS X support with the use of Darwin SSL. Thanks to these, we can now offer SSL-enabled libcurls on those operating systems without relying on third party SSL libraries.

- The VERIFYHOST debacle took off with “security researchers” throwing accusations and insults, ending with us releasing a curl release with the bug removed. It did however unfortunately lead to some follow-up problems in for example the PHP binding.

- During the autumn, the brokeness of WSApoll was identified, and we now build libcurl without it and as a result libcurl now works better on Windows!

- In an attempt to allow libcurl-using applications to avoid select() and its problems, we introduced the new public function curl_multi_wait. It avoids the FD_SETSIZE limit and makes it harder to screw up…

- The overly bloated User-Agent string for the curl tool was dramatically shortened when we cut out all the subsystems/libraries and their version numbers from the string. Now there’s only curl and its version number left. Nice and clean.

- In July we finally introduced metalink support in the curl tool with the curl 7.27.0 release. It’s been one of those things we’ve discussed for ages that finally came through and became reality.

- With the brand new HTTP CONNECT support in the test suite we suddenly could get much improved test cases that does SSL or just tunnel through an HTTP proxy with the CONNECT request. It of course helps us avoid regressions and otherwise improve curl and libcurl.

What didn’t happen

- I made an attempt to get the spindly hacking going, but I’ve mostly failed with that effort. I have personally not had enough time and energy to work on it, and the interest from the rest of the world seems luke warm at best.

- HTTP pipelining. Linus Nielsen Feltzing has a patch series in the works with a much improved pipelining support for libcurl. I’ll write a separate post about it once it gets in. Obviously we failed to merge it before the end of the year.

- Some of my friends like to mock me about curl not being completely IPv6 friendly due to its lack of support for Happy Eyeballs, and of course they’re right. Making curl just do two connects on IPv6-enabled machines should be a fairly small change but yet I haven’t yet managed to get into actually implementing it…

- DANE is SSL cert verification with records from DNS thanks to DNSSEC. Firefox has some experiments going and Chrome already supports it. This is a technology that truly can improve HTTPS going forwards and allow us to avoid the annoyingly weak and broken CA model…

I won’t promise that any of these will happen during 2013 but I can promise there will be efforts…

The Future

I wrote a separate post a short while ago about the HTTP2 progress, and I expect 2013 to bring much more details and discussions in that area. Will we get SRV record support soon? Or perhaps even URI records? Will some of the recent discussions about new HTTP auth schemes develop into something that will reach the internet in the coming year?

In libcurl we will switch to an internal design that is purely non-blocking with a lot of if-then-that-else source code removed for checks which interface that is used. I’ll make a follow-up post with details about that as well as soon as it actually happens.

Our Responsibility

curl and libcurl are considered pillars in the internet world by now. This year I’ve heard from several places by independent sources how people consider support by curl to be an important driver for internet technology. As long as we don’t have it, it hasn’t really reached everyone and that things won’t get adopted for real in the Internet community until curl has it supported. As father of the project it makes me proud and humble, but I also feel the responsibility of making sure that we continue to do the right thing the right way.

I also realize that this position of ours is not automatically glued to us, we need to keep up the good stuff to make it stick.

HTTP2, SPDY and spindly right now

On November 28, the HTTPbis group within the IETF published the first draft for the upcoming HTTP2 protocol. What is being posted now is a start and a foundation for further discussions and changes. It is basically an import of the SPDY version 3 protocol draft.

On November 28, the HTTPbis group within the IETF published the first draft for the upcoming HTTP2 protocol. What is being posted now is a start and a foundation for further discussions and changes. It is basically an import of the SPDY version 3 protocol draft.

There’s been a lot of resistance within the HTTPbis to the mandated TLS that SPDY has been promoting so far and it seems unlikely to reach a consensus as-is. There’s also been a lot of discussion and debate over the compression SPDY uses. Not only because of the pre-populated dictionary that might already be a little out of date or the fact that gzip compression consumes a notable amount of memory per stream, but also recently the security aspect to compression thanks to the CRIME attack.

Meanwhile, the discussions on the spdy development list have brought up several changes to the version 3 that are suggested and planned to become part of the version 4 that is work in progress. Including a new compression algorithm, shorter length fields (now 16bit) and more. Recently discussions have brought up a need for better flexibility when it comes to prioritization and especially changing prio run-time. For like when browser users switch tabs or simply scroll down the page and you rather have the images you have in sight to load before the images you no longer have in view…

I started my work on Spindly a little over a year ago to build a stand-alone library, primarily intended for libcurl so that we could soon offer SPDY downloads for it. We’re still only on SPDY protocol 2 there and I’ve failed to attract any fellow developers to the project and my own lack of time has basically made the project not evolve the way I wanted it to. I haven’t given up on it though. I hope to be able to get back to it eventually, very much also depending on how the HTTPbis talk goes. I certainly am determined to have libcurl be part of the upcoming HTTP2 experiments (even if that is not happening very soon) and spindly might very well be the infrastructure that powers libcurl then.

We’ll see…

HTTP2 Expression of Interest: curl

For the readers of my blog, this is a copy of what I posted to the httpbis mailing list on July 12th 2012.

Hi,

This is a response to the httpis call for expressions of interest

BACKGROUND

I am the project leader and maintainer of the curl project. We are the open source project that makes libcurl, the transfer library and curl the command line tool. It is among many things a client-side implementation of HTTP and HTTPS (and some dozen other application layer protocols). libcurl is very portable and there exist around 40 different bindings to libcurl for virtually all languages/enviornments imaginable. We estimate we might have upwards 500

million users or so. We’re entirely voluntary driven without any paid developers or particular company backing.

HTTP/1.1 problems I’d like to see adressed

Pipelining – I can see how something that better deals with increasing bandwidths with stagnated RTT can improve the end users’ experience. It is not easy to implement in a nice manner and provide in a library like ours.

Many connections – to avoid problems with pipelining and queueing on the connections, many connections are used and and it seems like a general waste that can be improved.

HTTP/2.0

We’ve implemented HTTP/1.1 and we intend to continue to implement any and all widely deployed transport layer protocols for data transfers that appear on the Internet. This includes HTTP/2.0 and similar related protocols.

curl has not yet implemented SPDY support, but fully intends to do so. The current plan is to provide SPDY support with the help of spindly, a separate SPDY library project that I lead.

We’ve selected to support SPDY due to the momentum it has and the multiple existing implementaions that A) have multi-company backing and B) prove it to be a truly working concept. SPDY seems to address HTTP’s pipelining and many-connections problems in a decent way that appears to work in reality too. I believe SPDY keeps enough HTTP paradigms to be easily upgraded to for most parties, and yet the ones who can’t or won’t can remain with HTTP/1.1 without too much pain. Also, while Spindly is not production-ready, it has still given me the sense that implementing a SPDY protocol engine is not rocket science and that the existing protocol specs are good.

By relying on external libs for protocol and implementation details, my hopes is that we should be able to add support for other potentially coming HTTP/2.0-ish protocols that gets deployed and used in the wild. In the curl project we’re unfortunately rarely able to be very pro-active due to the nature of our contributors, which tends to make us follow the rest and implement and go with what others have already decided to go with.

I’m not aware of any competitors to SPDY that is deployed or used to any particular and notable extent on the public internet so therefore no other “HTTP/2.0 protocol” has been considered by us. The two biggest protocol details people will keep mention that speak against SPDY is SSL and the compression requirements, yet I like both of them. I intend to continue to participate in dicussions and technical arguments on the ietf-http-wg mailing list on HTTP details for as long as I have time and energy.

HTTP AUTH

curl currently supports Basic, Digest, NTLM and Negotiate for both host and proxy.

Similar to the HTTP protocol, we intend to support any widely adopted authentication protocols. The HOBA, SCRAM and Mutual auth suggestions all seem perfectly doable and fine in my perspective.

However, if there’s no proper logout mechanism provided for HTTP auth I don’t forsee any particular desire from browser vendor or web site creators to use any of these just like they don’t use the older ones either to any significant extent. And for automatic (non-browser) uses only, I’m not sure there’s motivation enough to add new auth protocols to HTTP as at least historically we seem to rarely be able to pull anything through that isn’t pushed for by at least one of the major browsers.

The “updated HTTP auth” work should be kept outside of the HTTP/2.0 work as far as possible and similar to how RFC2617 is separate from RFC2616 it should be this time around too. The auth mechnism should not be too tightly knit to the HTTP protocol.

The day we can clense connection-oriented authentications like NTLM from the HTTP world will be a happy day, as it’s state awareness is a pain to deal with in a generic HTTP library and code.

shorter HTTP requests for curl

Starting in curl 7.26.0 (due to be released at the end of May 2012), we will shrink the User-agent: header that curl sends by default in HTTP(S) requests to something much shorter! I suspect that this will raise some eyebrows out there so even though I’ve emailed about it to the curl-users list before I thought I’d better write it up and elaborate.

A default ‘curl localhost’ on Debian Linux makes 170 bytes get sent in that single request:

GET / HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: curl/7.24.0 (i486-pc-linux-gnu) libcurl/7.24.0 OpenSSL/1.0.0g zlib/1.2.6 libidn/1.23 libssh2/1.2.8 librtmp/2.3 Host: localhost Accept: */*

As you can see, the user-agent description takes up a large portion of that request, and this for really no good reason at all. Without sacrificing any functionality I shrunk the same request down to 71 bytes:

GET / HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: curl/7.24.0 Host: localhost Accept: */*

That means we shrunk it down to 41% of the original size. I’ll admit the example is a bit extreme and most other normal use cases will use longer host names and longer paths, but even for a URL like “https://daniel.haxx.se/docs/curl-vs-wget.html” we’re down to 50% of the original request size (100 vs 199).

Can we shrink it even more? Sure, we could leave out the version number too. I left it in there now only to allow some kind of statistics to get extracted. We can’t remove the entire header, we need to include a user-agent in requests since there are too many servers who won’t function properly otherwise.

And before anyone asks: this change is only for the curl command line tool and not for libcurl, the library. libcurl does in fact not send any user-agent at all by default…

Travel for fun or profit

As a protocol geek I love working in my open source projects curl, libssh2, c-ares and spindly. I also participate in a few related IETF working groups around these protocols, and perhaps primarily I enjoy the HTTPbis crowd.

Meanwhile, I’m a consultant during the day and most of my projects and assignments involve embedded systems and primarily embedded Linux. The protocol part of my life tends to be left to get practiced during my “copious” amount of spare time – you know that time after your work, after you’ve spent time with your family and played with your kids and done the things you need to do at home to keep the household in a decent shape. That time when the rest of the family has gone to bed and you should too but if you did when would you ever get time to do that fun things you really want to do?

IETF has these great gatherings every now and then and they’re awesome places to just drown in protocol mumbo jumbo for several days. They’re being hosted by various cities all over the world so often I deem them too far away or too awkward to go to, also a lot because I rarely have any direct monetary gain or compensation for going but rather I’d have to do it as a vacation and pay for it myself.

IETF 83 is going to be held in Paris during March 25-30 and it is close enough for me to want to go and HTTPbis and a few other interesting work groups are having scheduled meetings. I really considered going, at least to meet up with HTTP friends.

Something very rare instead happened that prevents me from going there! My customer (for whom I work full-time since about six months and shall remain nameless for now) asked me to join their team and go visit the large embedded conference ESC in San Jose, California in the exact same week! It really wasn’ t a hard choice for me, since this is my job and being asked to do something because I’m wanted is a nice feeling and position – and they’re paying me to go there. It will also be my first time in California even though I guess I won’t get time to actually see much of it.

I hope to write a follow-up post later on about what I’m currently working with, once it has gone public.

Top-3 curl bugs in 2011

This is a continuation of my little top-3 things in curl during 2011 which started with the top-3 changes 2011.

The changelog on the curl site lists 150 bugs fixed in the seven released of the year. The most import fixes in my view were…

Bug-fix 1: handle HTTP redirects to //hostname/path

Following redirects is one of the fundamentals of HTTP user agents and one of the primary things people use curl and libcurl for is to mimic browser to do automatic stuff on the web. Therefore it was even more embarrassing to realize that libcurl didn’t properly support the relative redirect when the Location: header doesn’t include the protocol but the host name. It basically means that the protocol shall remain (in reality that means HTTP or HTTPS) but it should move over to the new host and path. All browsers support this since ages ago. Since November 15th 2011, libcurl does too!

Bug-fix 2: inappropriate GSSAPI delegation

We had one security vulnerability announced in 2011 and this was it. I won’t try to blame someone else for this mistake, but there are some corners of curl and libcurl I’m not personally very familiar with and I would say the GSS stuff is one of those. In fact, even the actual GSS and GSSAPI technologies are mercy areas as far as my knowledge reaches so I was not at all aware of this feature or that we even made us of it… Of course it also turns out that there’s a certain amount of existing applications that need it so we now have that ability in the library again if enabled by an option.

Bug-fix 3: multi interface, connect fail continue to next IP

One of those silly bugs nobody would expect us to have at this point. It turned out the code for the multi interface didn’t properly move on to try the next IP in case a connect() failed and the host name had resolved to a number of addresses to try. A long term goal of mine is to remodel the internals of libcurl to always use the multi interface code and I would just wrap that interfact with some glue logic to offer the easy interface. For that to work (and for lots of other reasons of course), the multi interface simply must work for all of these things.

Additionally, this is another of those things that are hard to test for in the test suite as it would involve trickery on IP or TCP level and that’s not easy to accomplish in a portable manner.

libspdy

SPDY is a neat new protocol and possible contender to replace HTTP – at least in some areas and for some use cases. SPDY has been invented and developed mostly by Google engineers.

SPDY allows better usage of fewer TCP connections (since it sends multiple logical streams over a single physical TCP connection) and it helps clients overcome problems with TCP (like how a new connection starts slowly) while at the same time reducing latency and bandwidth requirements. Very similar to how channels are handled over an SSH connection.

Chrome of course already supports SPDY and Firefox has some early experimental support being worked on.

Of course there are also legitimate criticisms against SPDY as well, including subjects like how it makes caching proxies impossible (because everything goes over SSL), how it makes debugging a lot harder by using compressed headers, how it is impossible to extract just a single header from the stream due to its compression approach and how the compression state buffers make each individual stream use more memory than plain old HTTP (plain TCP) ones.

We can expect SPDY<=>HTTP gateways to appear so that nobody gets locked into either side of these protocols.

SPDY will provide faster transfers. libcurl is currently used for speed reasons in many cases. To me, it makes perfect sense to have libcurl use and try to use SPDY instead of HTTP exactly like how the browsers are starting to do it, so that the libcurl using applications will get their contents transferred faster.

My thinking is that we introduce some new magic option(s) that makes libcurl use SPDY, and for normal easy interface transfers it will remain to use a single connection for each new SPDY transfer, but if you use the multi interface and you enable pipelining you’ll instead make libcurl do multiple transfers over the same single SPDY connection (as long as you speak with the same server and port etc). From an application’s stand-point it shouldn’t make any difference, apart from being faster than otherwise. Just like we want it!

Implementation wise, I would like to use a reliable and efficient third-party library for the actual SPDY implementation. If there doesn’t exist any, we make one and run that one independently. I found libspdy, but I found some concerns about it (no mailing list, looks like one-man project, not C89 compliant, no API docs etc). I mailed the libspdy author, I hoping we’d sort out my doubts and then I’d base my continued work on that library.

After some time Thomas Roth, primary libspdy author, responded and during our subsequent email exchange I’ve gotten a restored faith and belief in this library and its direction. Not only did he fix the C89 compliance pretty quickly, he is also promising rather big changes that are pending to get committed within a week or so.

Comforted by what I’ve learned from Thomas, I’ll wait for his upcoming changes and I’ll join the soon to be created mailing list for the libspdy project and I’ll contribute some ideas and efforts to help shape it into the fine SPDY library we all want. I can only encourage other fellow SPDY library interested persons to do the same!

Updated: Join the SPDY library development

What SOCKS is good for

You ever wondered what SOCKS is good for these days?

To help us use the Internet better without having the surrounding be able to watch us as much as otherwise!

There’s basically two good scenarios and use areas for us ordinary people to use SOCKS:

- You’re a consultant or you’re doing some kind of work and you are physically connected to a customer’s or a friend’s network. You access the big bad Internet via their proxy or entirely proxy-less using their equipment and cables. This allows the network admin(s) to capture and snoop on your network traffic, be it on purpose or by mistake, as long as you don’t use HTTPS or other secure mechanisms. When surfing the web, it is very easily made to drop out of HTTPS and into HTTP by mistake. Also, even if you HTTPS to the world, the name resolves and more are still done unencrypted and will leak information.

- You’re using an open wifi network that isn’t using a secure encryption. Anyone else on that same area can basically capture anything you send and receive.

What you need to set it up? You run

ssh -D 8080 myname@myserver.example.com

… and once you’ve connected, you make sure that you change the network settings of your favourite programs (browsers, IRC clients, mail reader, etc) to reach the Internet using the SOCKS proxy on localhost port 8080. Now you’re done.

Now all your traffic will reach the Internet via your remote server and all traffic between that and your local machine is sent encrypted and secure. This of course requires that you have a server running OpenSSH somewhere, but don’t we all?

If you are behind another proxy in the first place, it gets a little more complicated but still perfectly doable. See my separate SSH through or over proxy document for details.

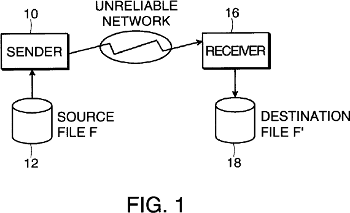

US patent 6,098,180

(I am not a lawyer, this is not legal advice and these are not legal analyses, just my personal observations and ramblings. Please correct me where I’m wrong or add info if you have any!)

At 3:45 pm on March 18th 2011, the company Content Delivery Solutions LLC filed a complaint in a court in Texas, USA. The defendants are several bigwigs and the list includes several big and known names of the Internet:

- Akamai

- AOL

- AT&T

- CD Networks

- Globalscape

- Limelight Networks

- Peer 1 Network

- Research In Motion

- Savvis

- Verizon

- Yahoo!

The complaint was later amended with an additional patent (filed on April 18th), making it list three patents that these companies are claimed to violate (I can’t find the amended version online though). Two of the patents ( 6,393,471 and 6,058,418) are for marketing data and how to use client info to present ads basically. The third is about file transfer resumes.

I was contacted by a person involved in the case at one of the defendants’. This unspecified company makes one or more products that use “curl“. I don’t actually know if they use the command line tool or the library – but I figure that’s not too important here. curl gets all its superpowers from libcurl anyway.

This Patent Troll thus basically claims that curl violates a patent on resumed file transfers!

The patent in question that would be one that curl would violate is the US patent 6,098,180 which basically claims to protect this idea:

A system is provided for the safe transfer of large data files over an unreliable network link in which the connection can be interrupted for a long period of time.

The patent describes several ways in how it may detect how it should continue the transfer from such a break. As curl only does transfer resumes based on file name and an offset, as told by the user/application, that could be the only method that they can say curl would violate of their patent.

The patent goes into detail in how a client first sends a “signature” and after an interruption when the file transfer is about to continue, the client would ask the server about details of what to send in the continuation. With a very vivid imagination, that could possibly equal the response to a FTP SIZE command or the Content-Length: response in a HTTP GET or HEAD request.

A more normal reader would rather say that no modern file transfer protocol works as described in that patent and we should go with “defendant is not infringing, move on nothing to see here”.

But for the sake of the argument, let’s pretend that the patent actually describes a method of file transfer resuming that curl uses.

The ‘180 (it is referred to with that name within the court documents) patent was filed at February 18th 1997 (and issued on August 1, 2000). Apparently we need to find prior art that was around no later than February 17th 1996, that is to say one year before the filing of the stupid thing. (This I’ve been told, I had no idea it could work like this and it seems shockingly weird to me.)

What existing tools and protocols did resumed transfers in February 1996 based on a file name and a file offset?

Lots!

Thank you all friends for the pointers and references you’ve brought to me.

- The FTP spec RFC 959 was published in October 1985. FTP has a REST command that tells at what offset to “restart” the transfer at. This was being used by FTP clients long before 1996, and an example is the known Kermit FTP client that did offset-based file resumed transfer in 1995.

- The HTTP header Range: introduces this kind of offset-based resumed transfer, although with a slightly fancier twist. The Range: header was discussed before the magic date, as also can be seen on the internet already in this old mailing list post from December 1995.

- One of the protocols from the old days that those of us who used modems and BBSes in the old days remember is zmodem. Zmodem was developed in 1986 and there’s this zmodem spec from 1988 describing how to do file transfer resumes.

- A slightly more modern protocol that I’ve unfortunately found no history for before our cut-off date is rsync, as I could only find the release mail for rsync 1.0 from June 1996. Still long before the patent was filed obviously, and also clearly showing that the one year margin is silly as for all we know they could’ve come up with the patent idea after reading the rsync releases notes and still rsync can’t be counted as prior art.

- Someone suggested GetRight as a client doing this, but GetRight wasn’t released in 1.0 until Febrary 1997 so unfortunately that didn’t help our case even if it seems to have done it at the time.

- curl itself does not pre-date the patent filing. curl was first released in March 1998, and the predecessor was started around summer-time 1997. I don’t have any remaining proofs of that, and it still wasn’t before “the date” so I don’t think it matters much now.

At the time of this writing I don’t know where this will end up or what’s going to happen. Time will tell.

This Software patent obviously is a concern mostly to US-based companies and those selling products in the US. I am neither a US citizen nor do I have or run any companies based in the US. However, since curl and libcurl are widely used products that are being used by several hundred companies already, I want to help bring out as much light as possible onto this problem.

The patent itself is of course utterly stupid and silly and it should never have been accepted as it describes trivially thought out ideas and concepts that have been thought of and implemented already decades before this patent was filed or granted although I claim that the exact way explained in the patent is not frequently used. Possibly the protocol using a method that is closed to the description of the patent is zmodem.

I guess I don’t have to mention what I think about software patents.

I’m convinced that most or all download tools and browsers these days know how to resume a previously interrupted transfer this way. Why wouldn’t these guys also approach one of the big guys (with thick wallets) who also use this procedure? Surely we can think of a few additional major players with file tools that can resume file transfers and who weren’t targeted in this suit!

I don’t know why. Clearly they’ve not backed down from attacking some of the biggest tech and software companies.

(Illustration from the ‘180 patent.)