tldr: curl goes back to Hackerone.

When we announced the end of the curl bug-bounty at the end of January 2026, we simultaneously moved over and started accepting curl security reports on GitHub instead of its previous platform.

This move turns out to have been a mistake and we are now undoing that part of the decision. The reward money is still gone, there is no bug-bounty, no money for vulnerability reports, but we return to accepting and handling curl vulnerability and security reports on Hackerone. Starting March 1st 2026, this is now (again) the official place to report security problems to the curl project.

This zig-zagging is unfortunate but we do it with the best of intentions. In the curl security team we were naively thinking that since so many projects are already using this setup it should be good enough for us too since we don’t have any particular special requirements. We wrongly thought. Now I instead question how other Open Source projects can use this. It feels like an area and use case for Open Source projects that is under-focused: proper, secure and efficient vulnerability reporting without bug-bounty.

What we want from a security reporting system

To illustrate what we are looking for, I made a little list that should show that we’re not looking for overly crazy things.

- Incoming submissions are reports that identify security problems.

- The reporter needs an account on the system.

- Submissions start private; only accessible to the reporter and the curl security team

- All submissions must be disclosed and made public once dealt with. Both correct and incorrect ones. This is important. We are Open Source. Maximum transparency is key.

- There should be a way to discuss the problem amongst security team members, the reporter and per-report invited guests.

- It should be possible to post security-team-only messages that the reporter and invited guests cannot see

- For confirmed vulnerabilities, an advisory will be produced that the system could help facilitate

- If there’s a field for CVE, make it possible to provide our own. We are after all our own CNA.

- Closed and disclosed reports should be clearly marked as invalid/valid etc

- Reports should have a tagging system so that they can be marked as “AI slop” or other terms for statistical and metric reasons

- Abusive users should be possible to ban/block from this program

- Additional (customizable) requirements for the privilege of submitting reports is appreciated (rate limit, time since account creation, etc)

What’s missing in GitHub’s setup?

Here is a list of nits and missing features we fell over on GitHub that, had we figured them out ahead of time, possibly would have made us go about this a different way. This list might interest fellow maintainers having the same thoughts and ideas we had. I have provided this feedback to GitHub as well – to make sure they know.

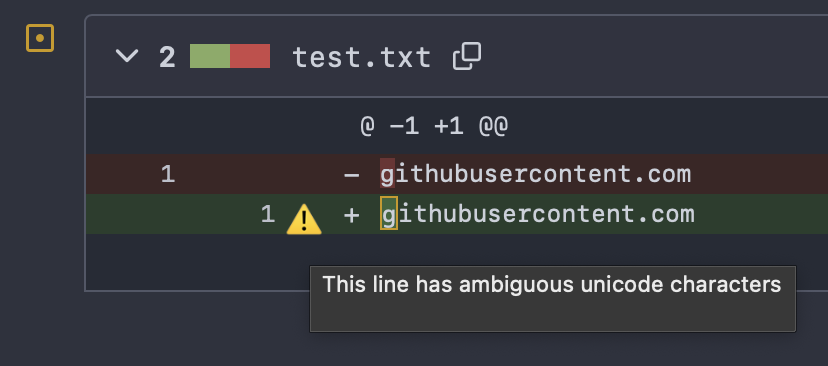

- GitHub sends the whole report over email/notification with no way to disable this. SMTP and email is known for being insecure and cannot assure end to end protection. This risks leaking secrets early to the entire email chain.

- We can’t disclose invalid reports (and make them clearly marked as such)

- Per-repository default collaborators on GitHub Security Advisories is annoying to manage, as we now have to manually add the security team for each advisory or have a rather quirky workflow scripting it. https://github.com/orgs/community/discussions/63041

- We can’t edit the CVE number field! We are a CNA, we mint our own CVE records so this is frustrating. This adds confusion.

- We want to (optionally) get rid of the CVSS score + calculator in the form as we actively discourage using those in curl CVE records

- No CI jobs working in private forks is going to make us effectively not use such forks, but is not a big obstacle for us because of our vulnerability working process. https://github.com/orgs/community/discussions/35165

- No “quote” in the discussions? That looks… like an omission.

- We want to use GitHub’s security advisories as the report to the project, not the final advisory (as we write that ourselves) which might get confusing, as even for the confirmed ones, the project advisories (hosted elsewhere) are the official ones, not the ones on GitHub

- No number of advisories count is displayed next to “security” up in the tabs, like for issues and Pull requests. This makes it hard to see progress/updates.

- When looking at an individual advisory, there is no direct button/link to go back to the list of current advisories

- In an advisory, you can only “report content”, there is no direct “block user” option like for issues

- There is no way to add private comments for the team-only, as when discussing abuse or details not intended for the reporter or other invited persons in the issue

- There is a lack of short (internal) identifier or name per issue, which makes it annoying and hard to refer to specific reports when discussing them in the security team. The existing identifiers are long and hard to differentiate from each other.

- You quite weirdly cannot get completion help for

@nickin comments to address people that were added into the advisory thanks to them being in a team you added to the issue? - There are no labels, like for issues and pull requests, which makes it impossible for us to for example mark the AI slop ones or other things, for statistics, metrics and future research

Email?

Sure, we could switch to handling them all over email but that also has its set of challenges. Including:

- Hard to keep track of the state of each current issue when a number of them are managed in parallel. Even just to see how many cases are still currently open or in need of attention.

- Hard to publish and disclose the invalid ones, as they never cause an advisory to get written and we rather want the initial report and the full follow-up discussion published.

- Hard to adapt to or use a reputation system beyond just the boolean “these people are banned”. I suspect that we over time need to use more crowdsourced knowledge or reputation based on how the reporters have behaved previously or in relation to other projects.

Onward and upward

Since we dropped the bounty, the inflow tsunami has dried out substantially. Perhaps partly because of our switch over to GitHub? Perhaps it just takes a while for all the sloptimists to figure out where to send the reports now and perhaps by going back to Hackerone we again open the gates for them? We just have to see what happens.

We will keep iterating and tweaking the program, the settings and the hosting providers going forward to improve. To make sure we ship a robust and secure set of products and that the team doing so can do that

Security problems?

If you suspect a security problem in curl or libcurl, report it here: https://hackerone.com/curl

The other forges don’t even try

Gitlab, Codeberg and others are GitHub alternatives and competitors, but few of them offer this kind of security reporting feature. That makes them bad alternatives or replacements for us for this particular service.