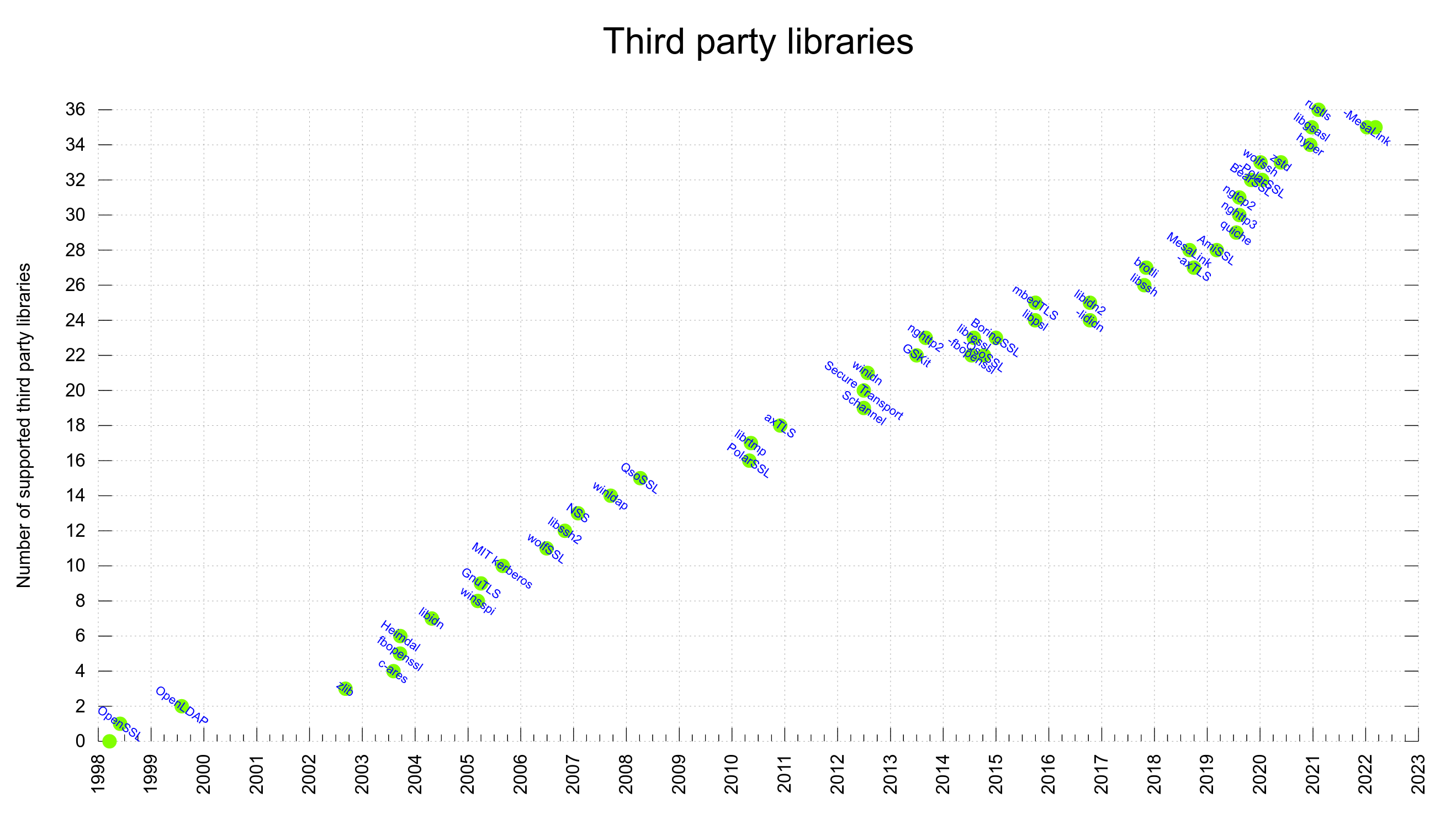

Vodafone UK has taken it on themselves to make the world better by marking this website (daniel.haxx.se) “adult content”. I suppose in order to protect the children.

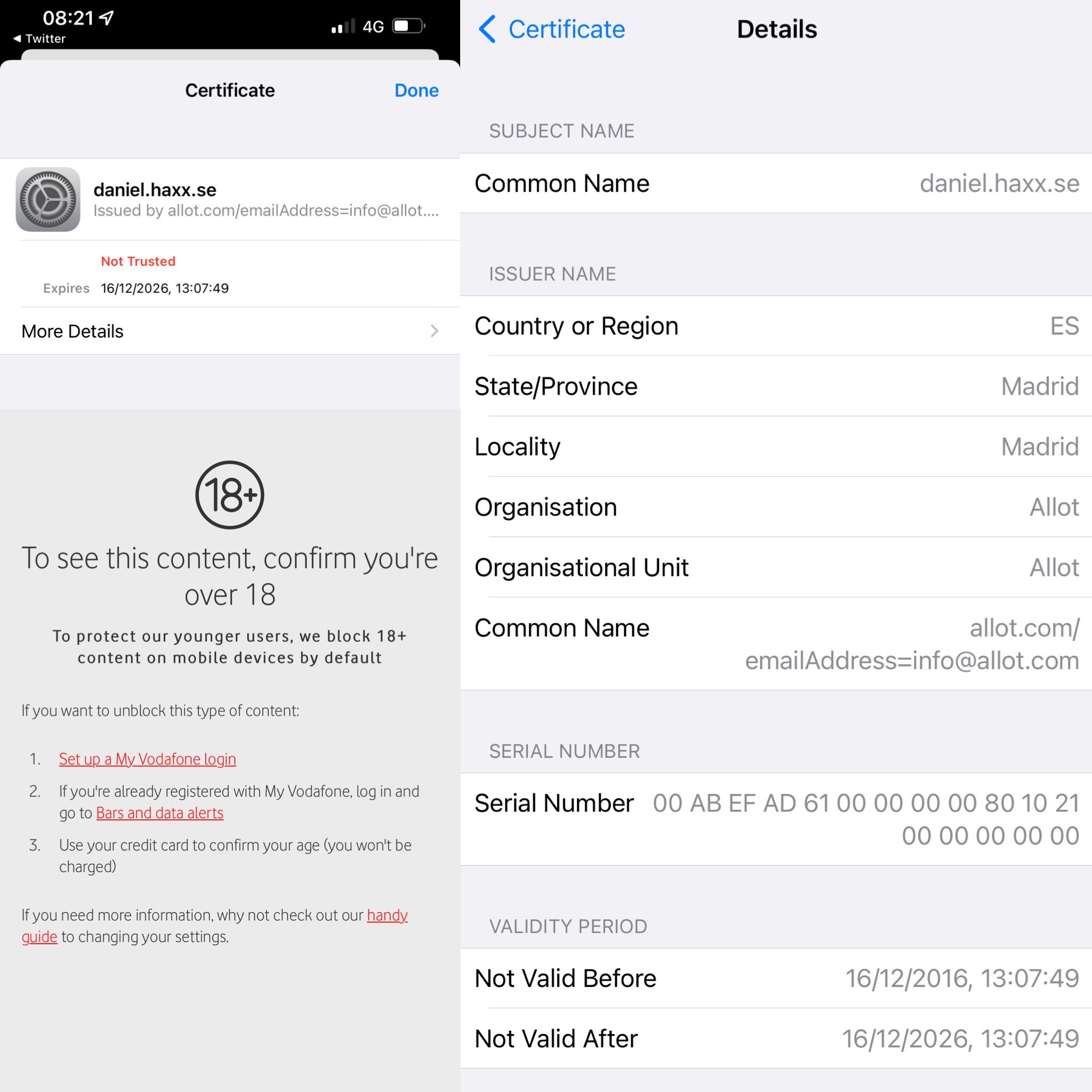

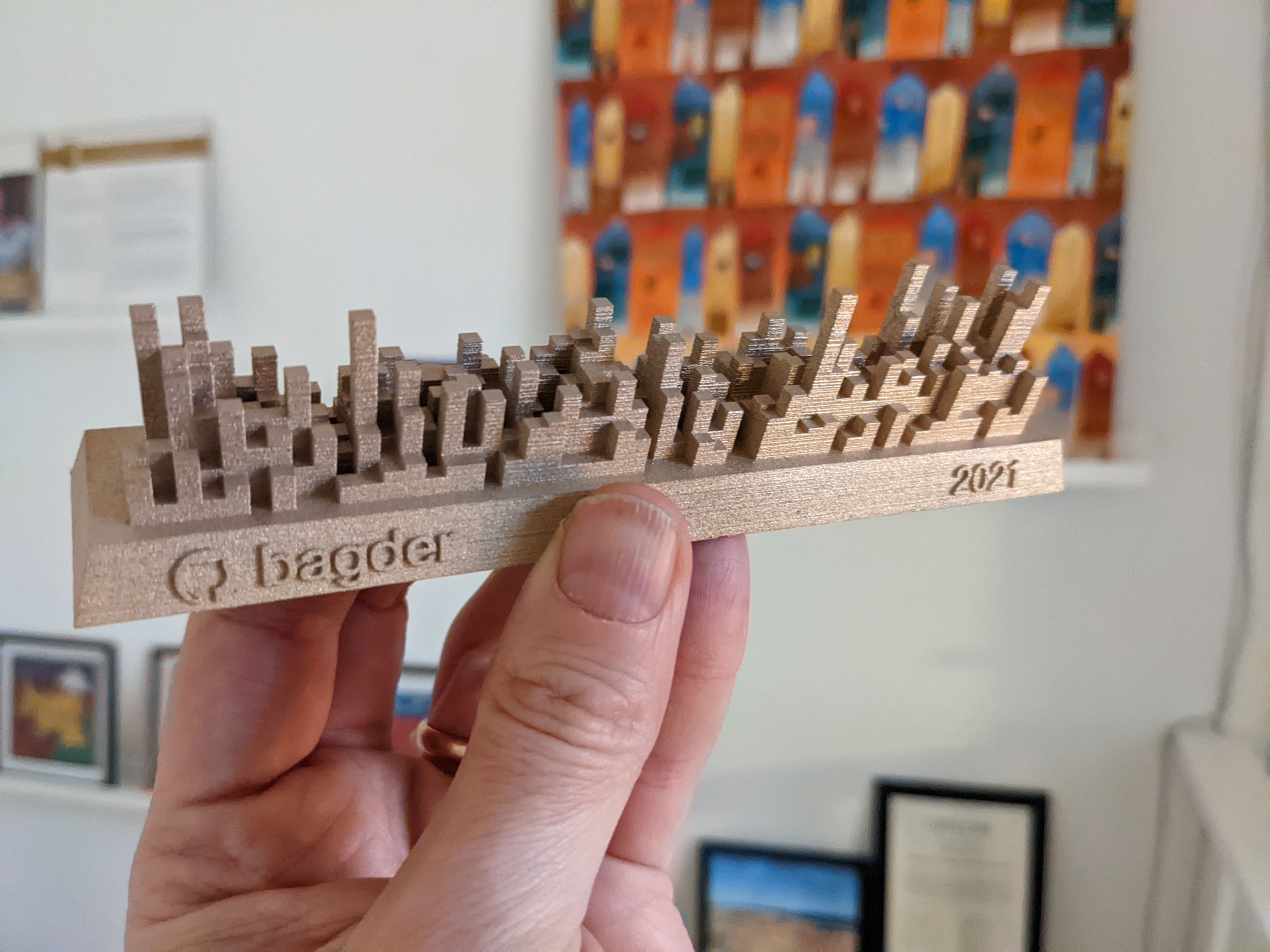

It was first reported to me on May 2, with this screenshot from a Vodafone customer:

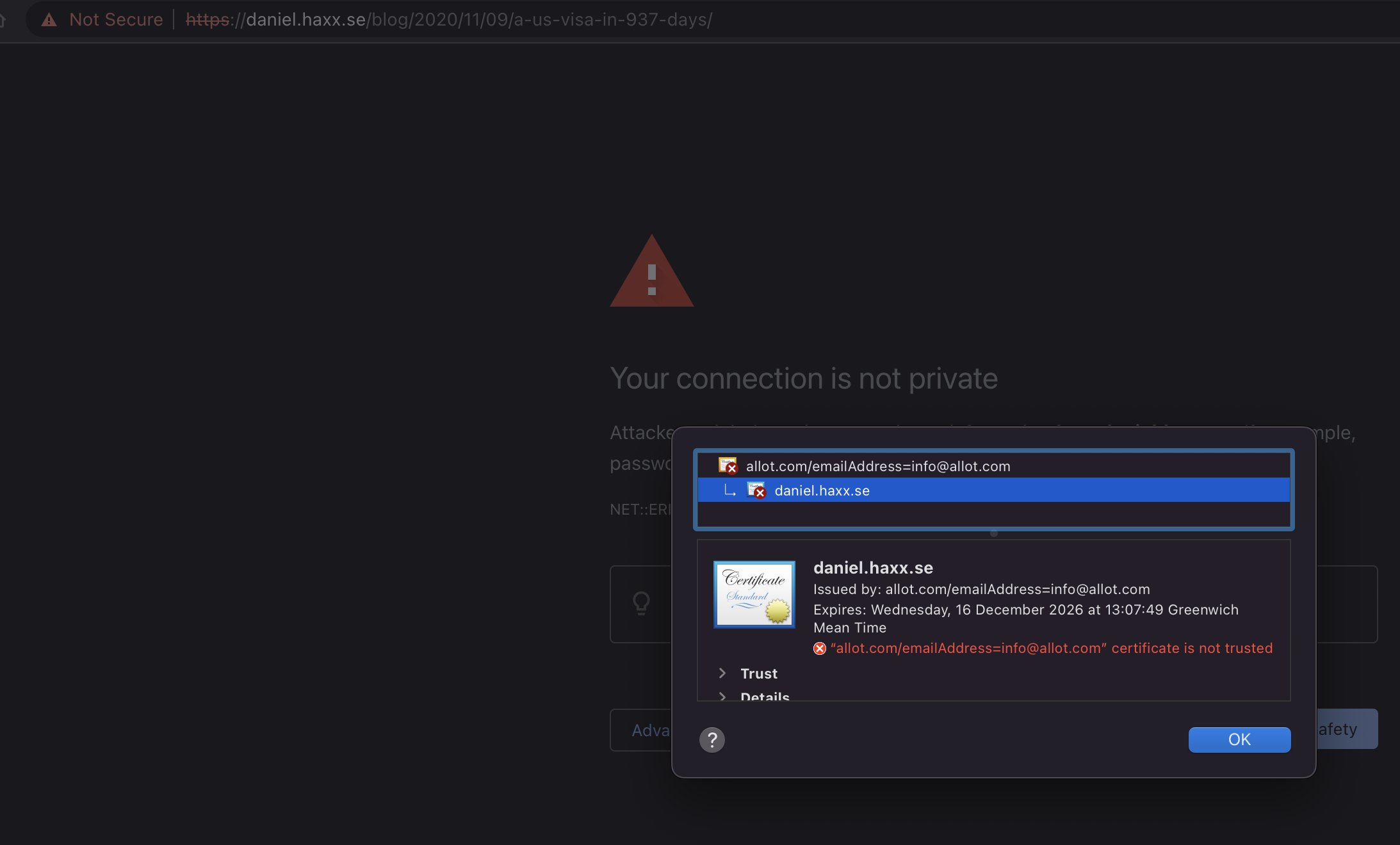

And later followed up with some more details from another user in this screenshot

Customers can opt out of this “protection” and then apparently Vodafone will no longer block my site.

How

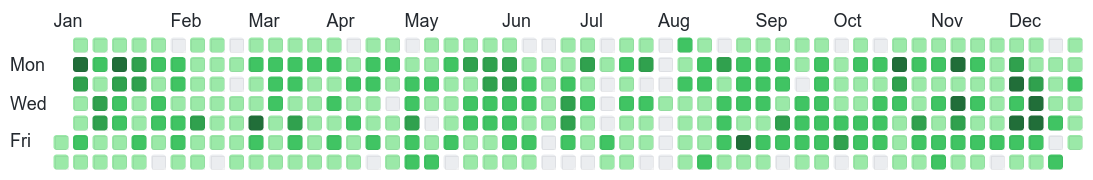

I was graciously given more logs (my copy) showing DNS resolves and curl command line invokes.

It shows that this filter is for this specific host name only, not for the entire haxx.se domain.

It also shows that the DNS resolves are unaffected as they returned the expected Fastly IP addresses just fine. I suspect they have equipment that inspects outgoing traffic that catches this TLS connection based on the SNI field.

As the log shows, they then make their server do a TLS handshake in which they respond with a certificate that has daniel.haxx.se in the CN field.

The curl verbose output shows this:

* SSL connection using TLSv1.2 / ECDHE-ECDSA-CHACHA20-POLY1305

* ALPN, server did not agree to a protocol

* Server certificate:

* subject: CN=daniel.haxx.se

* start date: Dec 16 13:07:49 2016 GMT

* expire date: Dec 16 13:07:49 2026 GMT

* issuer: C=ES; ST=Madrid; L=Madrid; O=Allot; OU=Allot; CN=allot.com/emailAddress=info@allot.com

* SSL certificate verify result: self signed certificate in certificate chain (19), continuing anyway.

> HEAD / HTTP/1.1

> Host: daniel.haxx.se

> User-Agent: curl/7.79.1

> Accept: */*

> The allot.com clue is the technology they use for this filtering. To quote their website, you can “protect citizens” with it.

I am not unique, clearly this has also hit other website owners. I have no idea if there is any way to appeal against this classification or something, but if you are a Vodafone UK customer, I would be happy if you did and maybe linked me to a public issue about it.

Update

I was pointed to the page where you can request to unblock specific sites so I have done that now (at 12:00 May 2).

Update on May 3

My unblock request for daniel.haxx.se is apparently “on hold” according to the web site.

I got an email from an anonymous (self-proclaimed) insider who says he works at Allot, the company doing this filtering for Vodafone. In this email, he says

Most likely, Vodafone is using their parental control a threat protection module which works based on a DNS resolving.

and then

After the business logic decides to block the website, it tells the DNS server to reply with a custom IP to a server that always shows a block page, because how HTTPS works, there is no way to trick it, either with Self-signed certificate, or using a signed certificate for a different domain, hence the warning.

What is weird here is that this explanation does not quite match what I have seen the logs provided to me. They showed this filtering clearly not being DNS based – since the DNS resolves got the exact same IP address a non-filtered resolver does.

Someone on Vodafone UK could of course easily test this by simply using a different DNS server, like 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8.

Discussed on hacker news.

Update May 3, 2024: unblocked

Two years later the situation was the same and I wrote about it on Mastodon:

Just hours later I was emailed by a person who explained they are employed by Vodafone and they forwarded my post internally. The blocking should thereby be gone. The original block was wrongly applied and then my unblocking request from two years ago “never reached the responsible team”.

Another win for complaining in the public.