I’ve written the http2 explained document and I’ve done several talks about HTTP/2. I’ve gotten a lot of questions about TLS in association with HTTP/2 due to this, and I want to address some of them here.

TLS is not mandatory

In the HTTP/2 specification that has been approved and that is about to become an official RFC any day now, there is no language that mandates the use of TLS for securing the protocol. On the contrary, the spec clearly explains how to use it both in clear text (over plain TCP) as well as over TLS. TLS is not mandatory for HTTP/2.

TLS mandatory in effect

While the spec doesn’t force anyone to implement HTTP/2 over TLS but allows you to do it over clear text TCP, representatives from both the Firefox and the Chrome development teams have expressed their intents to only implement HTTP/2 over TLS. This means HTTPS:// URLs are the only ones that will enable HTTP/2 for these browsers. Internet Explorer people have expressed that they intend to also support the new protocol without TLS, but when they shipped their first test version as part of the Windows 10 tech preview, that browser also only supported HTTP/2 over TLS. As of this writing, there has been no browser released to the public that speaks clear text HTTP/2. Most existing servers only speak HTTP/2 over TLS.

The difference between what the spec allows and what browsers will provide is the key here, and browsers and all other user-agents are all allowed and expected to each select their own chosen path forward.

If you’re implementing and deploying a server for HTTP/2, you pretty much have to do it for HTTPS to get users. And your clear text implementation will not be as tested…

A valid remark would be that browsers are not the only HTTP/2 user-agents and there are several such non-browser implementations that implement the non-TLS version of the protocol, but I still believe that the browsers’ impact on this will be notable.

Stricter TLS

When opting to speak HTTP/2 over TLS, the spec mandates stricter TLS requirements than what most clients ever have enforced for normal HTTP 1.1 over TLS.

It says TLS 1.2 or later is a MUST. It forbids compression and renegotiation. It specifies fairly detailed “worst acceptable” key sizes and cipher suites. HTTP/2 will simply use safer TLS.

Another detail here is that HTTP/2 over TLS requires the use of ALPN which is a relatively new TLS extension, RFC 7301, which helps us negotiate the new HTTP version without losing valuable time or network packet round-trips.

TLS-only encourages more HTTPS

Since browsers only speak HTTP/2 over TLS (so far at least), sites that want HTTP/2 enabled must do it over HTTPS to get users. It provides a gentle pressure on sites to offer proper HTTPS. It pushes more people over to end-to-end TLS encrypted connections.

This (more HTTPS) is generally considered a good thing by me and us who are concerned about users and users’ right to privacy and right to avoid mass surveillance.

Why not mandatory TLS?

The fact that it didn’t get in the spec as mandatory was because quite simply there was never a consensus that it was a good idea for the protocol. A large enough part of the working group’s participants spoke up against the notion of mandatory TLS for HTTP/2. TLS was not mandatory before so the starting point was without mandatory TLS and we didn’t manage to get to another stand-point.

When I mention this in discussions with people the immediate follow-up question is…

No really, why not mandatory TLS?

The motivations why anyone would be against TLS for HTTP/2 are plentiful. Let me address the ones I hear most commonly, in an order that I think shows the importance of the arguments from those who argued them.

1. A desire to inspect HTTP traffic

There is a claimed “need” to inspect or intercept HTTP traffic for various reasons. Prisons, schools, anti-virus, IPR-protection, local law requirements, whatever are mentioned. The absolute requirement to cache things in a proxy is also often bundled with this, saying that you can never build a decent network on an airplane or with a satellite link etc without caching that has to be done with intercepts.

Of course, MITMing proxies that terminate SSL traffic are not even rare these days and HTTP/2 can’t do much about limiting the use of such mechanisms.

2. Think of the little ones

“Small devices cannot handle the extra TLS burden“. Either because of the extra CPU load that comes with TLS or because of the cert management in a billion printers/fridges/routers etc. Certificates also expire regularly and need to be updated in the field.

Of course there will be a least acceptable system performance required to do TLS decently and there will always be systems that fall below that threshold.

3. Certificates are too expensive

The price of certificates for servers are historically often brought up as an argument against TLS even it isn’t really HTTP/2 related and I don’t think it was ever an argument that was particularly strong against TLS within HTTP/2. Several CAs now offer zero-cost or very close to zero-cost certificates these days and with the upcoming efforts like letsencrypt.com, chances are it’ll become even better in the not so distant future.

Recently someone even claimed that HTTPS limits the freedom of users since you need to give personal information away (he said) in order to get a certificate for your server. This was not a price he was willing to pay apparently. This is however simply not true for the simplest kinds of certificates. For Domain Validated (DV) certificates you usually only have to prove that you “control” the domain in question in some way. Usually by being able to receive email to a specific receiver within the domain.

4. The CA system is broken

TLS of today requires a PKI system where there are trusted certificate authorities that sign certificates and this leads to a situation where all modern browsers trust several hundred CAs to do this right. I don’t think a lot of people are happy with this and believe this is the ultimate security solution. There’s a portion of the Internet that advocates for DANE (DNSSEC) to address parts of the problem, while others work on gradual band-aids like Certificate Transparency and OCSP stapling to make it suck less.

My personal belief is that rejecting TLS on the grounds that it isn’t good enough or not perfect is a weak argument. TLS and HTTPS are the best way we currently have to secure web sites. I wouldn’t mind seeing it improved in all sorts of ways but I don’t believe running protocols clear text until we have designed and deployed the next generation secure protocol is a good idea – and I think it will take a long time (if ever) until we see a TLS replacement.

Who were against mandatory TLS?

Yeah, lots of people ask me this, but I will refrain from naming specific people or companies here since I have no plans on getting into debates with them about details and subtleties in the way I portrait their arguments. You can find them yourself if you just want to and you can most certainly make educated guesses without even doing so.

What about opportunistic security?

A text about TLS in HTTP/2 can’t be complete without mentioning this part. A lot of work in the IETF these days are going on around introducing and making sure opportunistic security is used for protocols. It was also included in the HTTP/2 draft for a while but was moved out from the core spec in the name of simplification and because it could be done anyway without being part of the spec. Also, far from everyone believes opportunistic security is a good idea. The opponents tend to say that it will hinder the adoption of “real” HTTPS for sites. I don’t believe that, but I respect that opinion because it is a guess as to how users will act just as well as my guess is they won’t act like that!

Opportunistic security for HTTP is now being pursued outside of the HTTP/2 spec and allows clients to upgrade plain TCP connections to instead do “unauthenticated TLS” connections. And yes, it should always be emphasized: with opportunistic security, there should never be a “padlock” symbol or anything that would suggest that the connection is “secure”.

Firefox supports opportunistic security for HTTP and it will be enabled by default from Firefox 37.

Translated versions of this blogpost

TLS in HTTP/2 (Russian)

TLS in HTTP/2 (Kazakh)

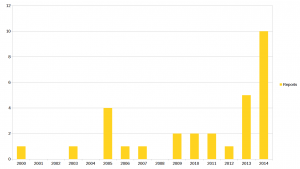

curl first implemented cookie support way back in the early days in the late 90s. I participated in the IETF work that much later

curl first implemented cookie support way back in the early days in the late 90s. I participated in the IETF work that much later