But will it satisfy the world?

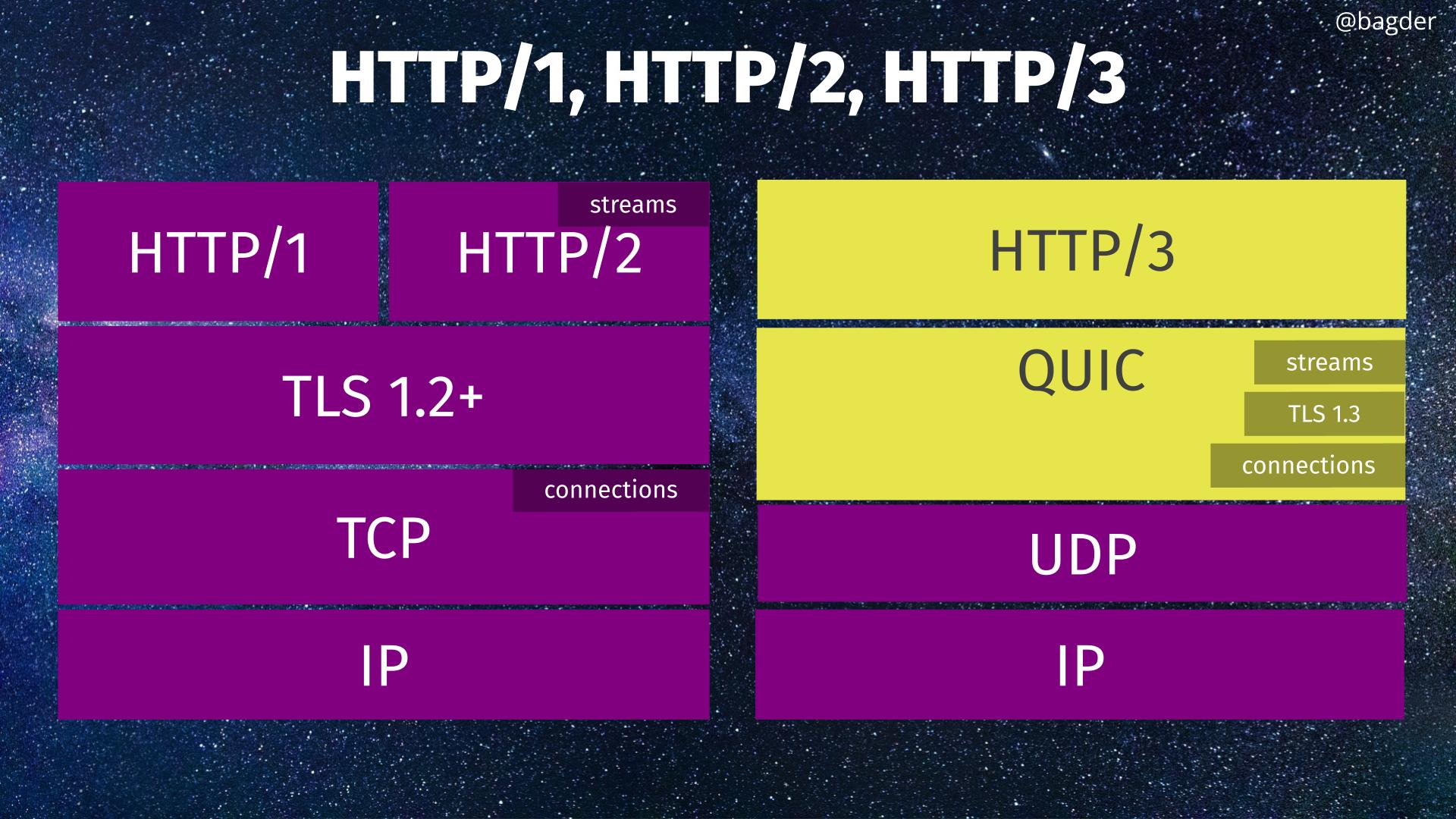

I have blogged several times in the past about how OpenSSL decided to not ship the API for QUIC a long time ago, even though the entire HTTP world was hoping for it – or even expecting it. OpenSSL rejected the proposal to merge the proposed API and thereby implicitly decided to obstruct wide QUIC and HTTP/3 adoption outside browsers.

The OpenSSL team instead proclaimed that their ambition and goal was to implement their own QUIC stack and offer that to users. The OpenSSL team took a long time to implement it, but has shipped their own stack implementation and API since OpenSSL 3.2 – first released in November 2023.

Lagging behind

In the curl project we have been on top of this game all the way. We made curl capable of using OpenSSL-QUIC as a backend for QUIC (using nghttp3 for the HTTP/3 parts) as soon as that arrived. We immediately reported obvious flaws and omissions in their API and we have worked with the OpenSSL team over time as they have slowly but gradually addressed most (but not all) of our concerns.

Lots of other QUIC stack implementations have spent years in beta state, working out and polishing their implementations and APIs. OpenSSL went fairly quickly into shipping something they say can be used in production.

OpenSSL-QUIC considered experimental

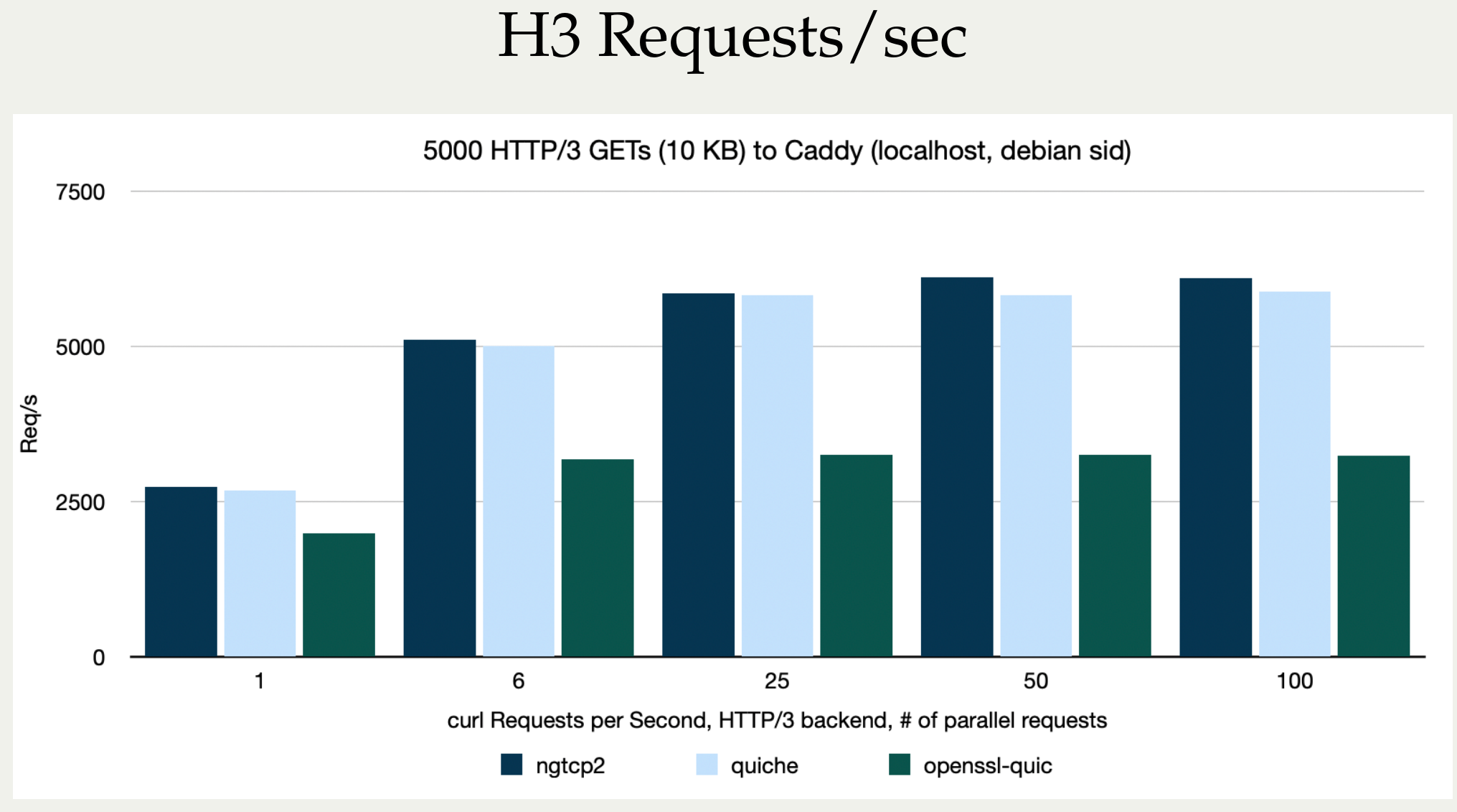

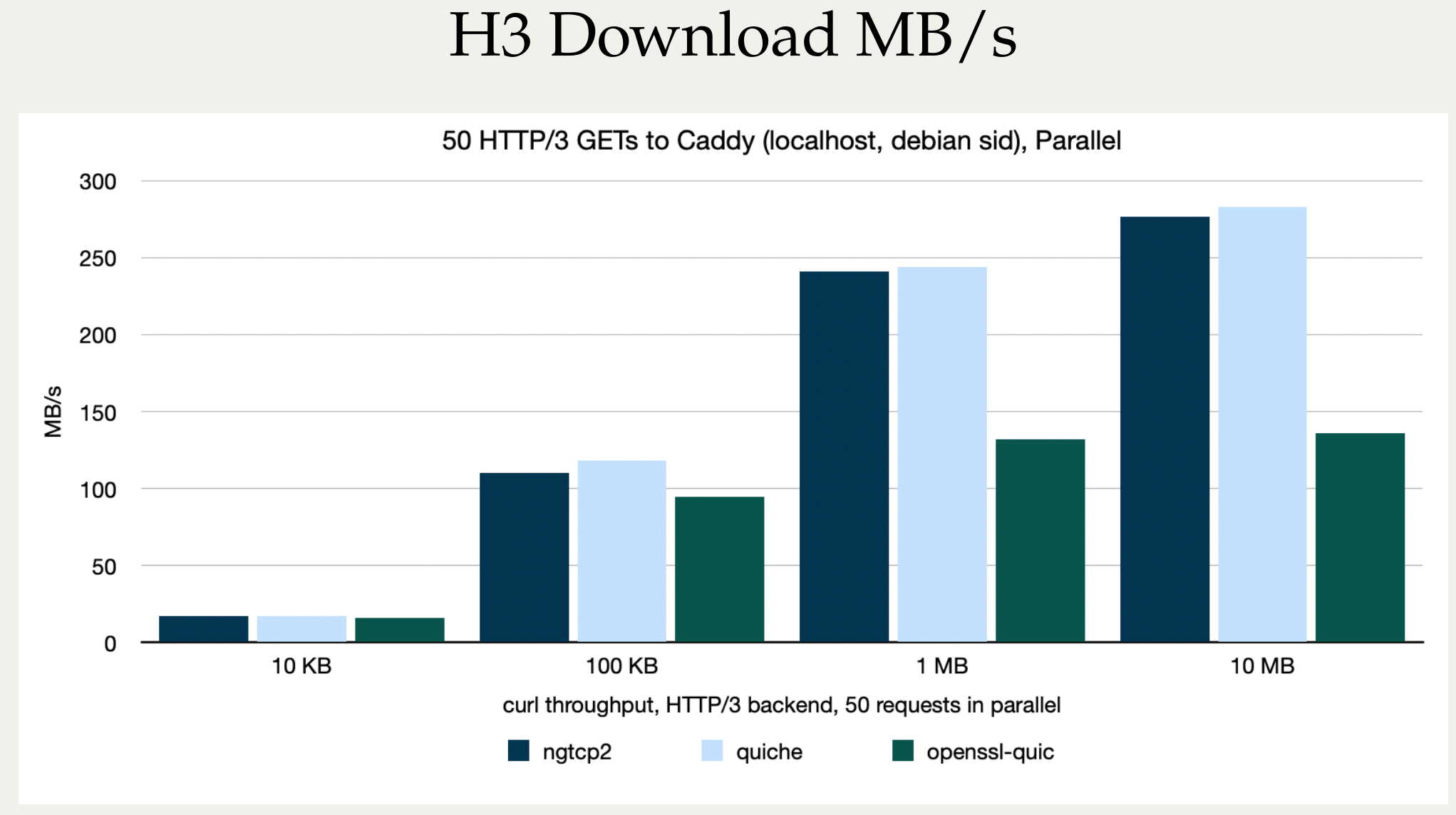

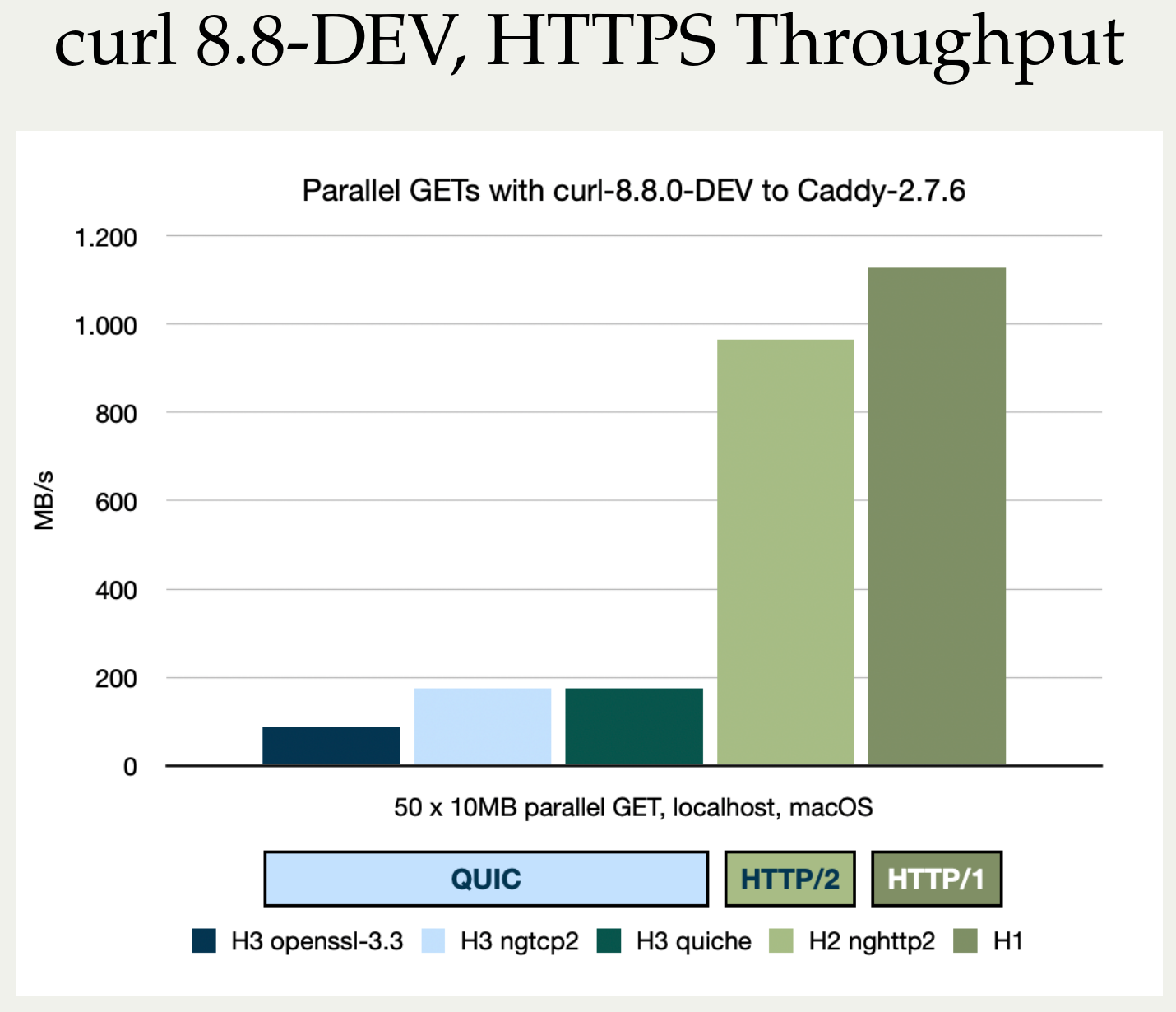

We still consider the curl backend using the OpenSSL-QUIC implementation as experimental and discourage users from using such builds in production. Now primarily because it is a performance and resource hog compared to the competition.

The OpenSSL-QUIC implementation using curl has been measured up to 4 times (!) slower than ngtcp2 using up to 25 times (!) the amount of memory.

The API is different

The API OpenSSL finally merged on February 10, 2025 is however not the exact same API that was proposed many years ago, the API that BoringSSL, quictls and the others have been offering for many years by now. It is different, and because of this the QUIC implementations that want to use it need to adapt specifically for this and cannot just interchangeably switch between the many OpenSSL forks. It uses a pull concept versus the push of what other provides.

Additionally, the pull requests mentions: At the moment our QUIC stack does not support early data. A significant missing feature compared to what the OpenSSL forks (and other libraries) support.

When I asked the OpenSSL team about how they came to ship such a different API to what everyone else offers and what QUIC implementers have been asking for, the given explanation was:

– The API is layered on what we use internally to plug in our QUIC client and server implementations in a clean manner […] We did get some feedback from other QUIC stacks – but the proof will be in actual usage which we expect will occur most likely after the 3.5 release is out.

Rumors have it that they say they spoke to four QUIC stack authors and they all had planned to support it.

I don’t know which four stacks this was, and I’m curious to see this happen. Most QUIC stacks are not written to handle different TLS libraries with different APIs, so they would either add that support now or switch to a different API all together. Either way, not a trivial undertaking.

Also “planning to support it” is easy to say. Could also just mean at some point in a distant future.

ngtcp2 is the world’s generic QUIC stack

There are multiple QUIC implementations out there, but the only one that has had the idea of being TLS library independent already from its start, is ngtcp2.

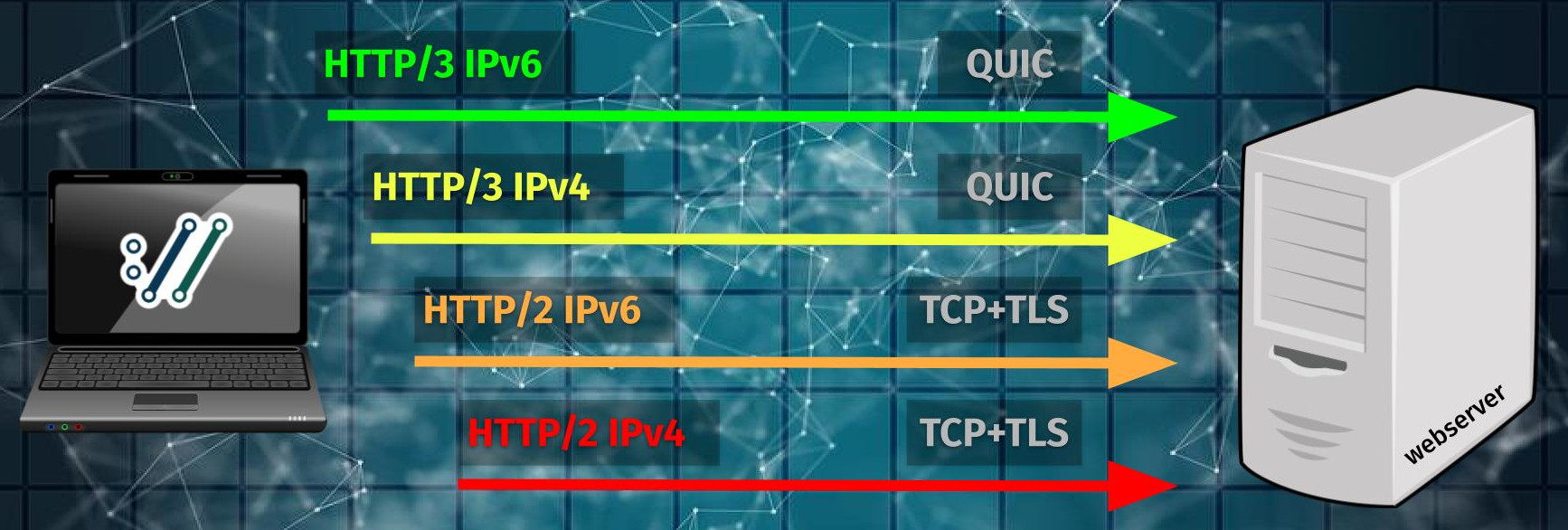

Since curl supports ngtcp2 for QUIC, it can then also work with any of the TLS libraries ngtcp2 supports: BoringSSL, AWS-LC, quictls, wolfSSL, GnuTLS. This fits the curl mindset very well.

ngtcp2 is also the only QUIC stack curl supports right now that is not considered experimental.

Could in theory ease HTTP/3 adoption

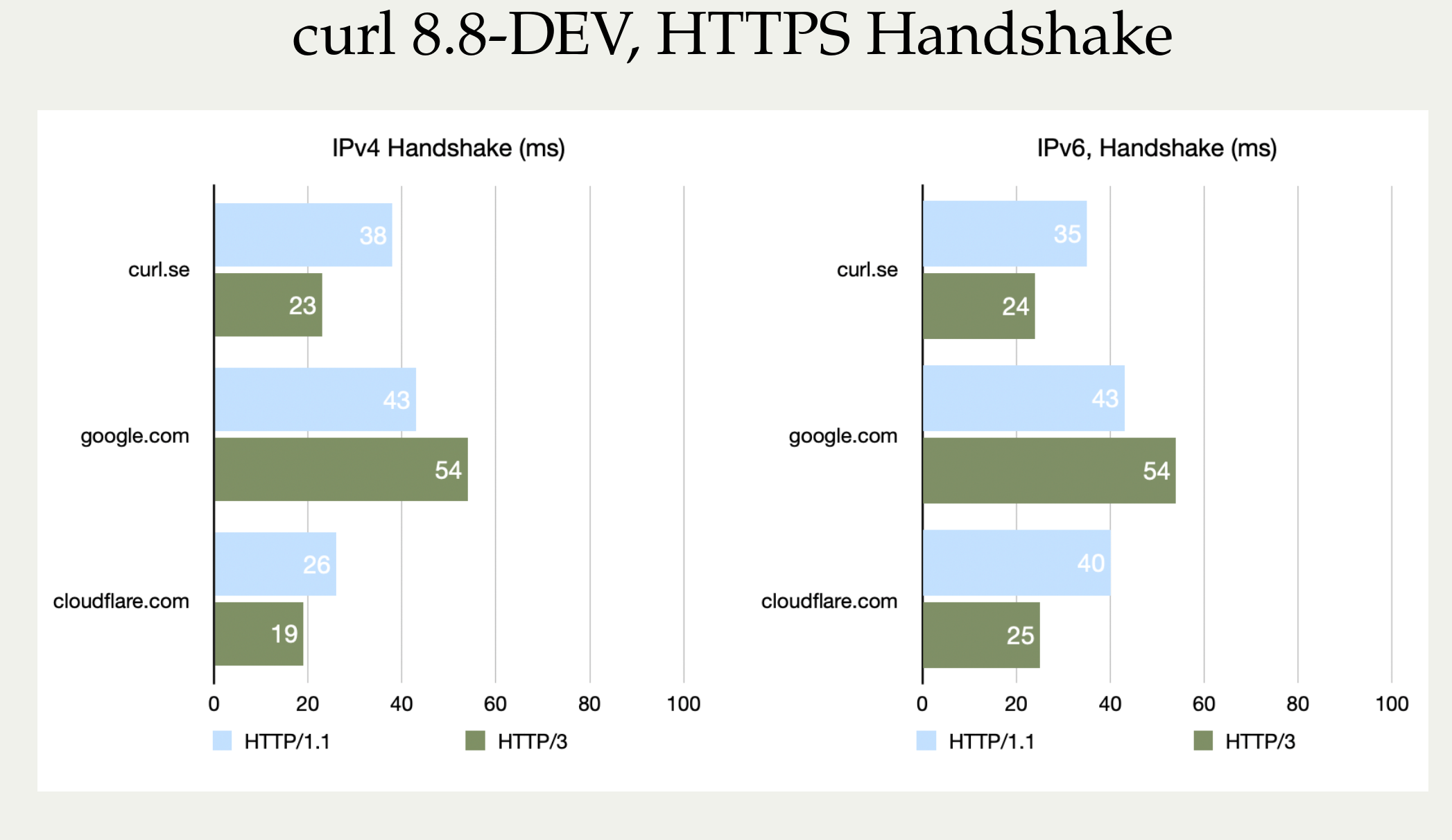

Assuming the API works, and assuming ngtcp2 can make use of the API in a fine way, this unexpected change of attitude could be the move that suddenly and for real makes HTTP/3 adoption in and with curl take off. OpenSSL has a firm grip of the TLS library landscape (in particular in the Open Source realm) and a huge share of curl users uses it. Starting with the pending OpenSSL version 3.5 in the spring of 2025, building with curl + OpenSSL can then possibly enable HTTP/3.

So will it? I asked a lead developer of the ngtcp2 library if they are going to work on adding an adaptation for the new OpenSSL 3.5 API.

– I have no plan to do that. OpenSSL QUIC API lacks 0rtt support and its pulling crypto data is not ideal for me, other TLS stacks do not do that. Basically, the current state is inferior than what we have proposed 6 years ago. I will revisit this after OpenSSL adds 0rtt support and revise its pull model.

(Clearly they were not one of the four stack authors OpenSSL talked to.)

While this does of course not prevent someone else from doing the work, even thought the 0RTT limitation is something that primarily has to be added to the OpenSSL API, it might imply that it will not happen immediately.

In my opinion, I think it could be useful and educational if the OpenSSL project themselves wrote that adaptation for ngtcp2 to “dogfood” their own API.

curl

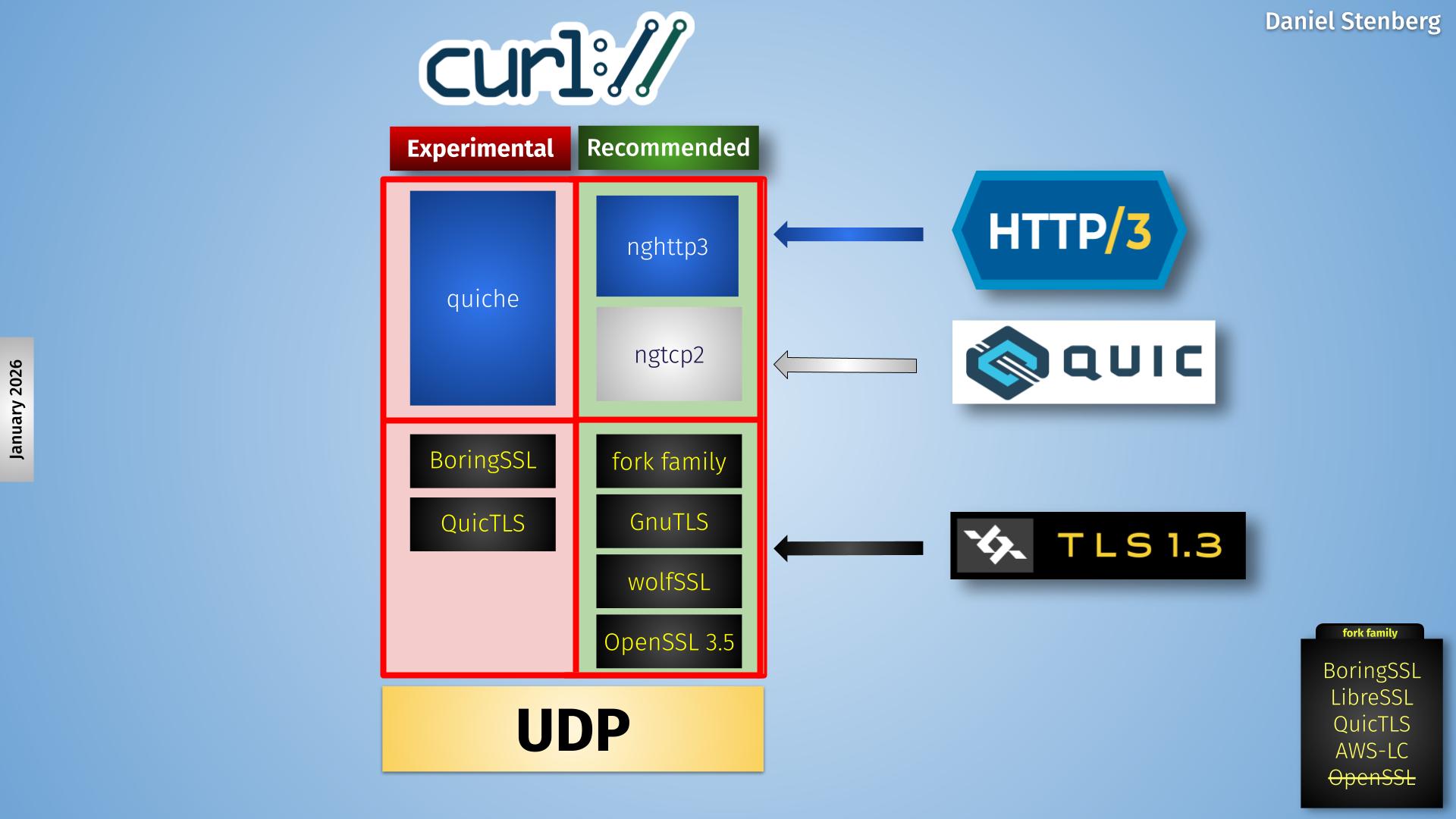

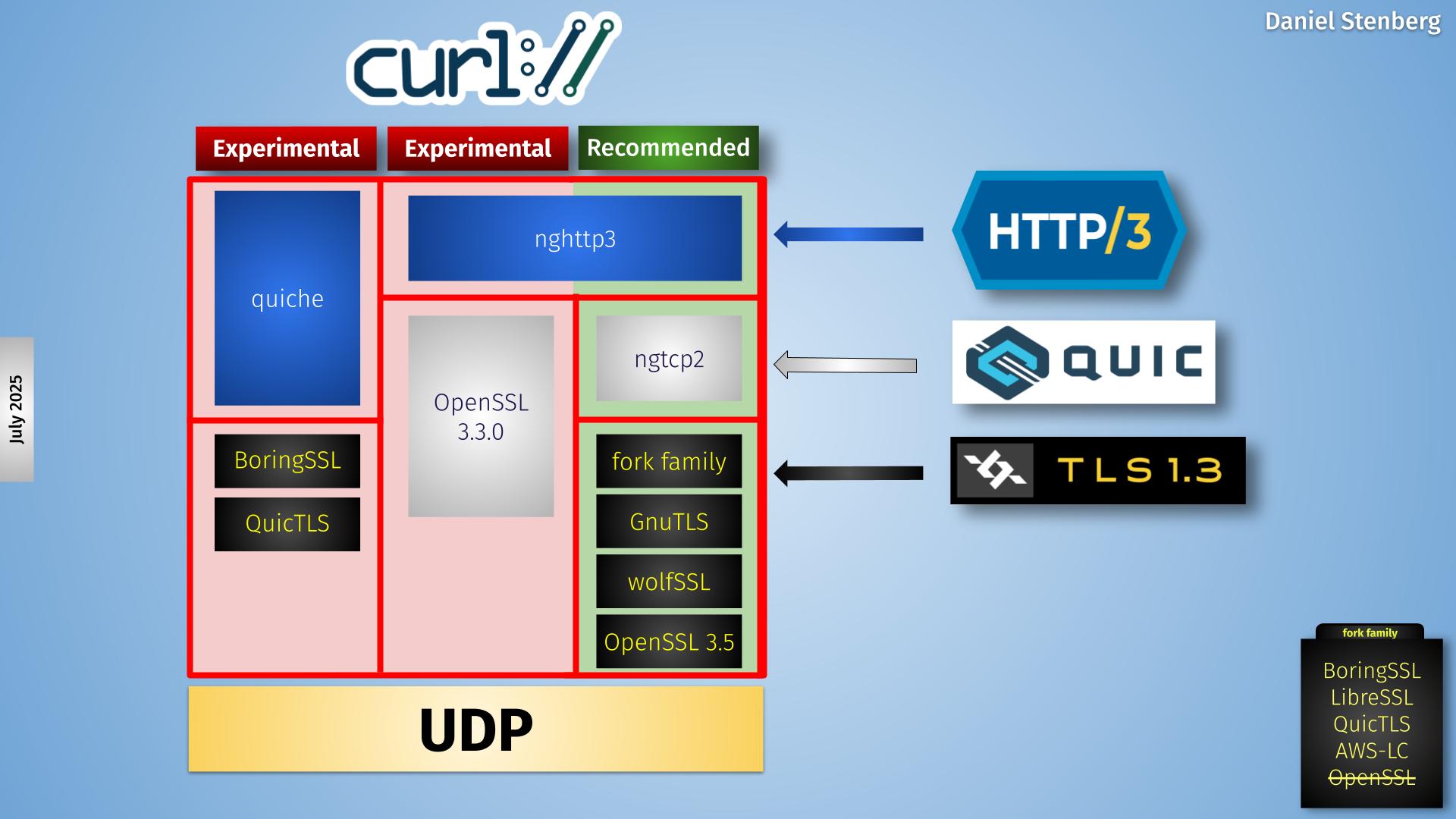

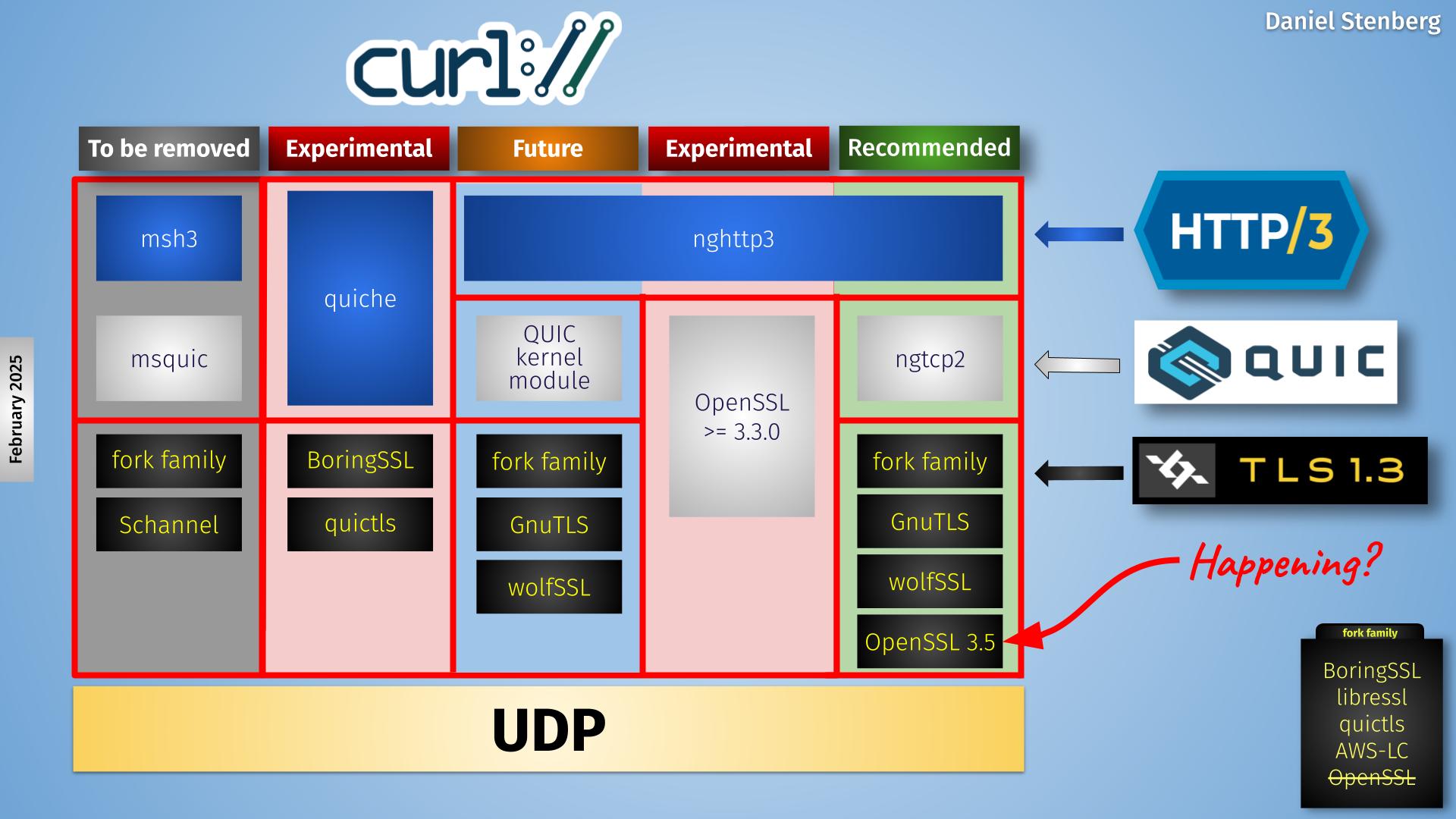

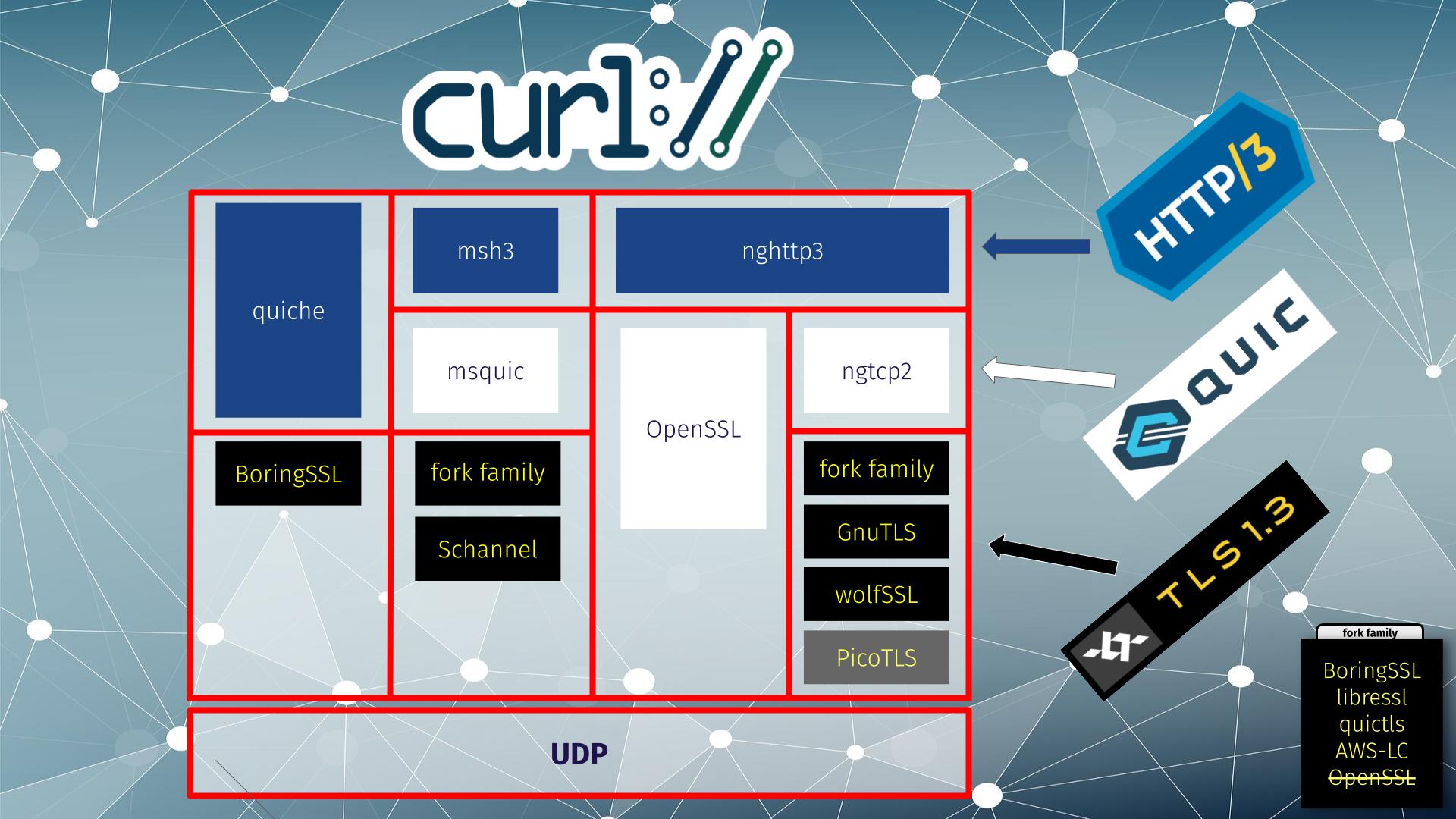

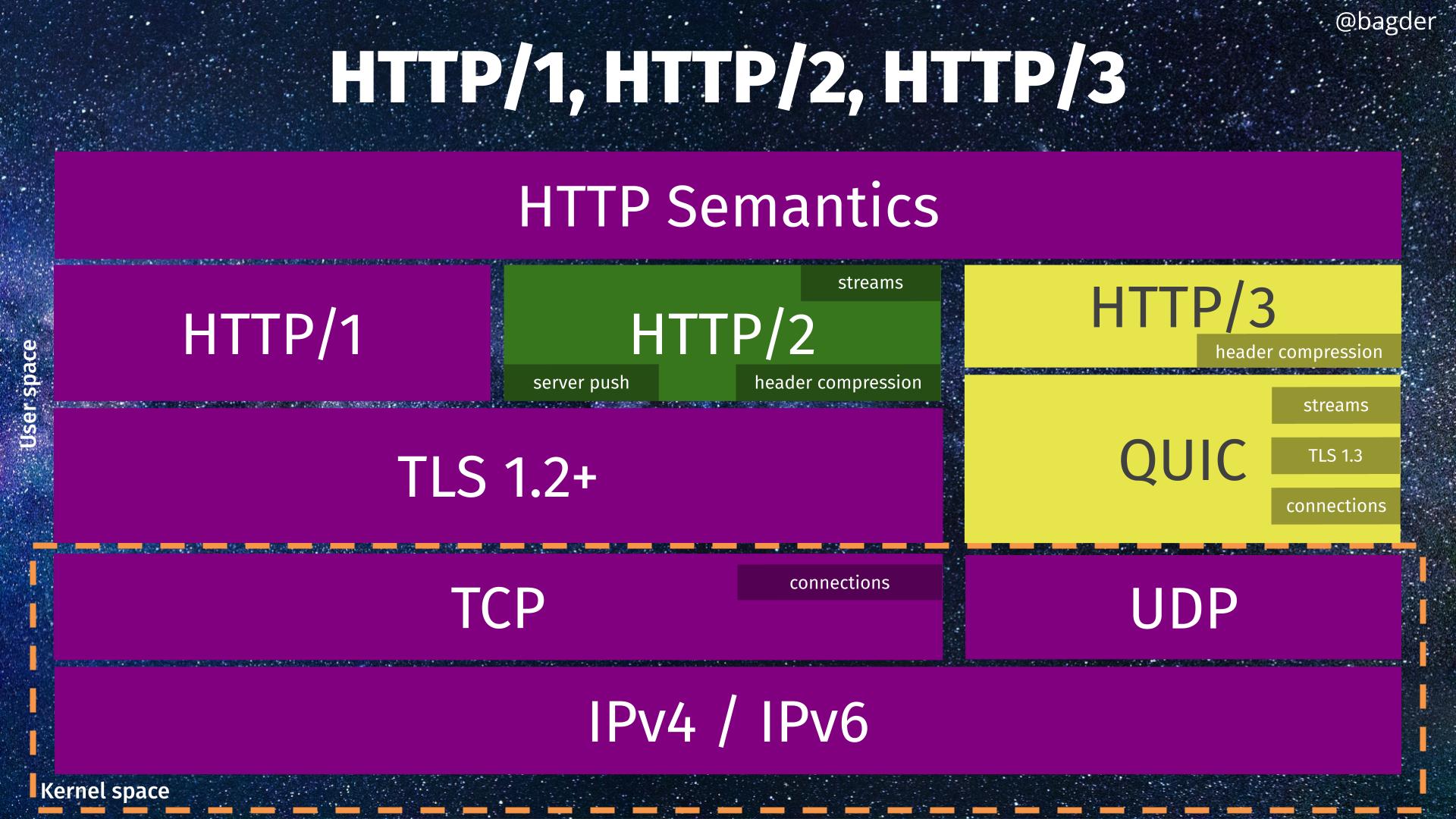

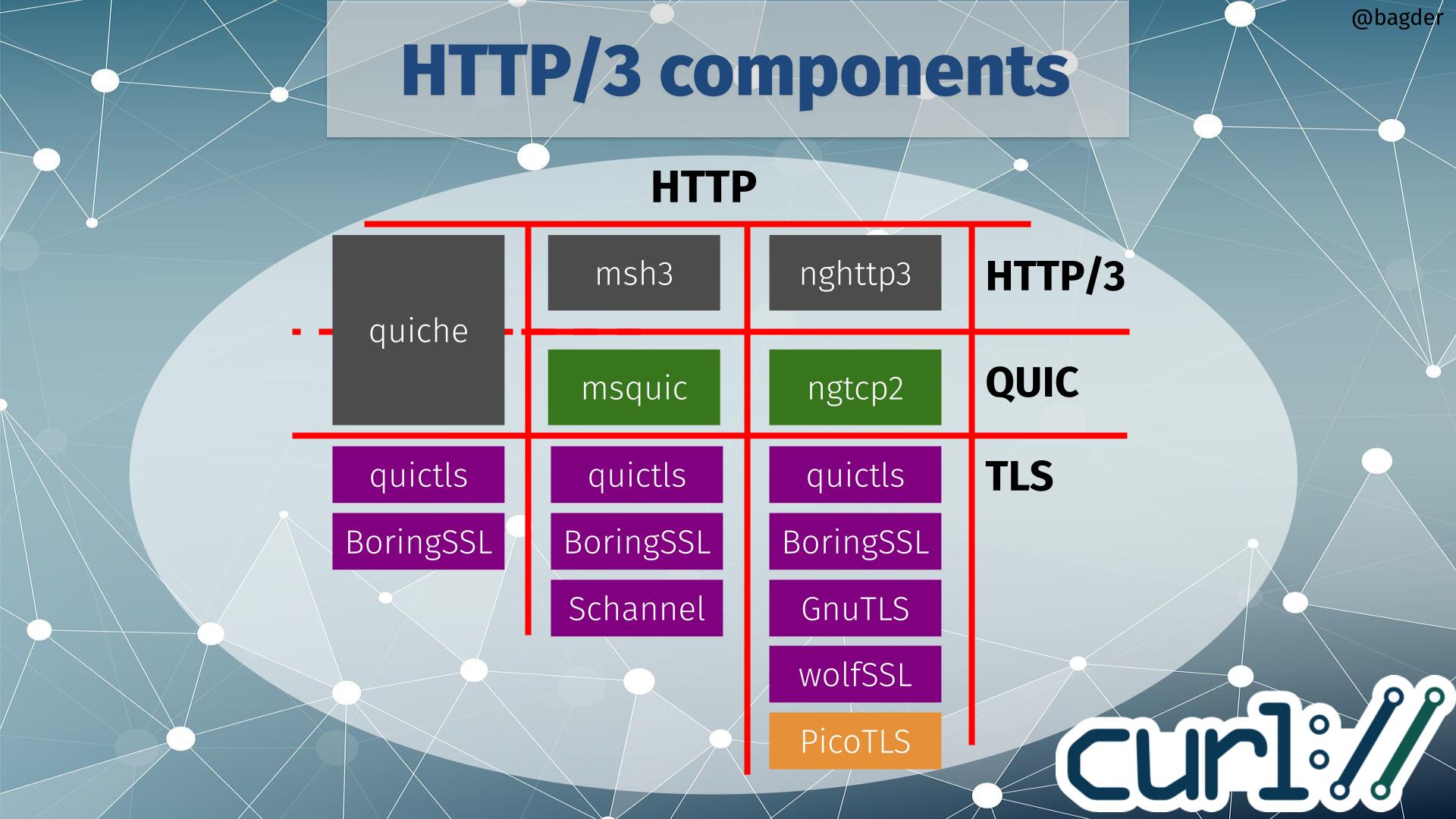

An attempt to illustrate the QUIC stack situation in current curl is shown below.

Currently curl supports four backends, out of which one (msh3) is scheduled for removal later this year and one (the kernel module version) is still only proposed for future inclusion – waiting for the kernel module to actually get adopted into the Linux kernel.

This leaves three actively developed backends, out of which one (ngtcp2) is the one we recommend and push for. The quiche and the OpenSSL-QUIC ones are still experimental.

The new OpenSSL API I discuss in this blog post is the one that would populate the lower right box, providing a TLS API for the QUIC library running on top of it. Hence me putting the red “happening?” text for this puzzle piece.

The red column second from the right is the OpenSSL-QUIC solution, using OpenSSL’s QUIC implementation.

Early days

It has not even been a week since this new API was merged into OpenSSL’s git repository, so it is far too early to give any predictions. Presumably it won’t even be used much for real by others until it gets shipped in a public release, planned to happen in April 2025.

Update

On February 26, there was another OpenSSL update: the QUIC API now offers 0-RTT support and they say this will be part of what ships in 3.5.