When I started the precursor to the curl project, httpget, back in 1996, I wrote my first URL parser. Back then, the universal address was still called URL: Uniform Resource Locators. That spec was published by the IETF in 1994. The term “URL” was then used as source for inspiration when naming the tool and project curl.

The term URL was later effectively changed to become URI, Uniform Resource Identifiers (published in 2005) but the basic point remained: a syntax for a string to specify a resource online and which protocol to use to get it. We claim curl accepts “URLs” as defined by this spec, the RFC 3986. I’ll explain below why it isn’t strictly true.

There was also a companion RFC posted for IRI: Internationalized Resource Identifiers. They are basically URIs but allowing non-ascii characters to be used.

The WHATWG consortium later produced their own URL spec, basically mixing formats and ideas from URIs and IRIs with a (not surprisingly) strong focus on browsers. One of their expressed goals is to “Align RFC 3986 and RFC 3987 with contemporary implementations and obsolete them in the process“. They want to go back and use the term “URL” as they rightfully state, the terms URI and IRI are just confusing and no humans ever really understood them (or often even knew they exist).

The WHATWG spec follows the good old browser mantra of being very liberal in what it accepts and trying to guess what the users mean and bending backwards trying to fulfill. (Even though we all know by now that Postel’s Law is the wrong way to go about this.) It means it’ll handle too many slashes, embedded white space as well as non-ASCII characters.

From my point of view, the spec is also very hard to read and follow due to it not describing the syntax or format very much but focuses far too much on mandating a parsing algorithm. To test my claim: figure out what their spec says about a trailing dot after the host name in a URL.

On top of all these standards and specs, browsers offer an “address bar” (a piece of UI that often goes under other names) that allows users to enter all sorts of fun strings and they get converted over to a URL. If you enter “http://localhost/%41” in the address bar, it’ll convert the percent encoded part to an ‘A’ there for you (since 41 in hex is a capital A in ASCII) but if you type “http://localhost/A A” it’ll actually send “/A%20A” (with a percent encoded space) in the outgoing HTTP GET request. I’m mentioning this since people will often think of what you can enter there as a “URL”.

The above is basically my (skewed) perspective of what specs and standards we have so far to work with. Now we add reality and let’s take a look at what sort of problems we get when my URL isn’t your URL.

So what is a URL?

Or more specifically, how do we write them. What syntax do we use.

I think one of the biggest mistakes the WHATWG spec has made (and why you will find me argue against their spec in its current form with fierce conviction that they are wrong), is that they seem to believe that URLs are theirs to define and work with and they limit their view of URLs for browsers, HTML and their address bars. Sure, they are the big companies behind the browsers almost everyone uses and URLs are widely used by browsers, but URLs are still much bigger than so.

The WHATWG view of a URL is not widely adopted outside of browsers.

colon-slash-slash

If we ask users, ordinary people with no particular protocol or web expertise, what a URL is what would they answer? While it was probably more notable years ago when the browsers displayed it more prominently, the :// (colon-slash-slash) sequence will be high on the list. Seeing that marks the string as a URL.

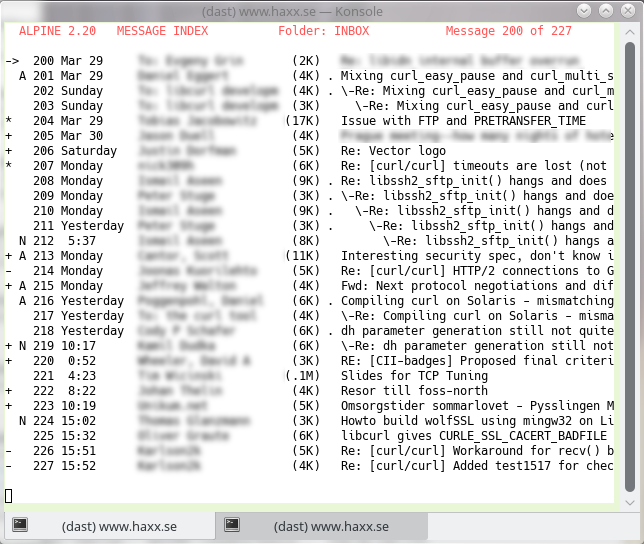

Heck, going beyond users, there are email clients, terminal emulators, text editors, perl scripts and a bazillion other things out there in the world already that detects URLs for us and allows operations on that. It could be to open that URL in a browser, to convert it to a clickable link in generated HTML and more. A vast amount of said scripts and programs will use the colon-slash-slash sequence as a trigger.

The WHATWG spec says it has to be one slash and that a parser must accept an indefinite amount of slashes. “http:/example.com” and “http:////////////////////////////////////example.com” are both equally fine. RFC 3986 and many others would disagree. Heck, most people I’ve confronted the last few days, even people working with the web, seem to say, think and believe that a URL has two slashes. Just look closer at the google picture search screen shot at the top of this article, which shows the top images for “URL” google gave me.

We just know a URL has two slashes there (and yeah, file: URLs most have three but lets ignore that for now). Not one. Not three. Two. But the WHATWG doesn’t agree.

“Is there really any reason for accepting more than two slashes for non-file: URLs?” (my annoyed question to the WHATWG)

“The fact that all browsers do.”

The spec says so because browsers have implemented the spec.

No better explanation has been provided, not even after I pointed out that the statement is wrong and far from all browsers do. You may find reading that thread educational.

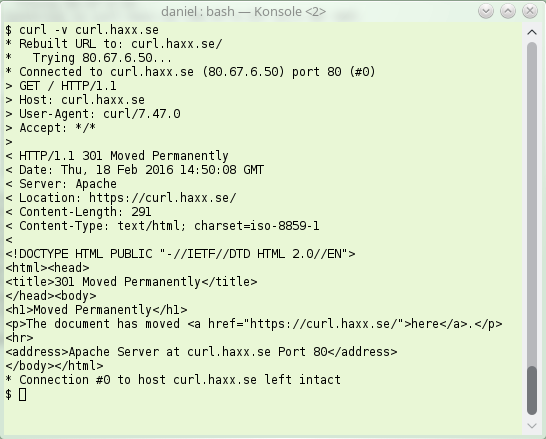

In the curl project, we’ve just recently started debating how to deal with “URLs” having another amount of slashes than two because it turns out there are servers sending back such URLs in Location: headers, and some browsers are happy to oblige. curl is not and neither is a lot of other libraries and command line tools. Who do we stand up for?

Spaces

A space character (the ASCII code 32, 0x20 in hex) cannot be part of a URL. If you want it sent, you percent encode it like you do with any other illegal character you want to be part of the URL. Percent encoding is the byte value in hexadecimal with a percent sign in front of it. %20 thus means space. It also means that a parser that for example scans for URLs in a text knows that it reaches the end of the URL when the parser encounters a character that isn’t allowed. Like space.

Browsers typically show the address in their address bars with all %20 instances converted to space for appearance. If you copy the address there into your clipboard and then paste it again in your text editor you still normally get the spaces as %20 like you want them.

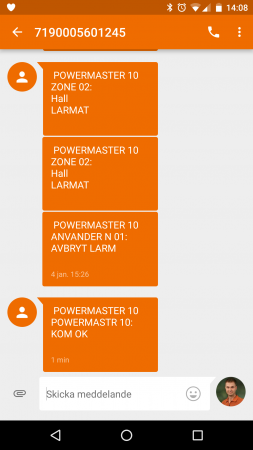

I’m not sure if that is the reason, but browsers also accept spaces as part of URLs when for example receiving a redirect in a HTTP response. That’s passed from a server to a client using a Location: header with the URL in it. The browsers happily allow spaces in that URL, encode them as %20 and send out the next request. This forced curl into accepting spaces in redirected “URLs”.

Non-ASCII

Making URLs support non-ASCII languages is of course important, especially for non-western societies and I’ve understood that the IRI spec was never good enough. I personally am far from an expert on these internationalization (i18n) issues so I just go by what I’ve heard from others. But of course users of non-latin alphabets and typing systems need to be able to write their “internet addresses” to resources and use as links as well.

In an ideal world, we would have the i18n version shown to users and there would be the encoded ASCII based version below, to get sent over the wire.

For international domain names, the name gets converted over to “punycode” so that it can be resolved using the normal system name resolvers that know nothing about non-ascii names. URIs have no IDN names, IRIs do and WHATWG URLs do. curl supports IDN host names.

WHATWG states that URLs are specified as UTF-8 while URIs are just ASCII. curl gets confused by non-ASCII letters in the path part but percent encodes such byte values in the outgoing requests – which causes “interesting” side-effects when the non-ASCII characters are provided in other encodings than UTF-8 which for example is standard on Windows…

Similar to what I’ve written above, this leads to servers passing back non-ASCII byte codes in HTTP headers that browsers gladly accept, and non-browsers need to deal with…

No URL standard

I’ve not tried to write a conclusive list of problems or differences, just a bunch of things I’ve fallen over recently. A “URL” given in one place is certainly not certain to be accepted or understood as a “URL” in another place.

Not even curl follows any published spec very closely these days, as we’re slowly digressing for the sake of “web compatibility”.

There’s no unified URL standard and there’s no work in progress towards that. I don’t count WHATWG’s spec as a real effort either, as it is written by a closed group with no real attempts to get the wider community involved.

My affiliation

I’m employed by Mozilla and Mozilla is a member of WHATWG and I have colleagues working on the WHATWG URL spec and other work items of theirs but it makes absolutely no difference to what I’ve written here. I also participate in the IETF and I consider myself friends with authors of RFC 1738, RFC 3986 and others but that doesn’t matter here either. My opinions are my own and this is my personal blog.

erver sending back an instruction to the client – instead of giving back the contents the client wanted. The server basically says “go look over [here] instead for that thing you asked for“.

erver sending back an instruction to the client – instead of giving back the contents the client wanted. The server basically says “go look over [here] instead for that thing you asked for“.