“the overall impression of the state of security and robustness

of the cURL library was positive.”

I asked for, and we were granted a security audit of curl from the Mozilla Secure Open Source program a while ago. This was done by Mozilla getting a 3rd party company involved to do the job and footing the bill for it. The auditing company is called Cure53.

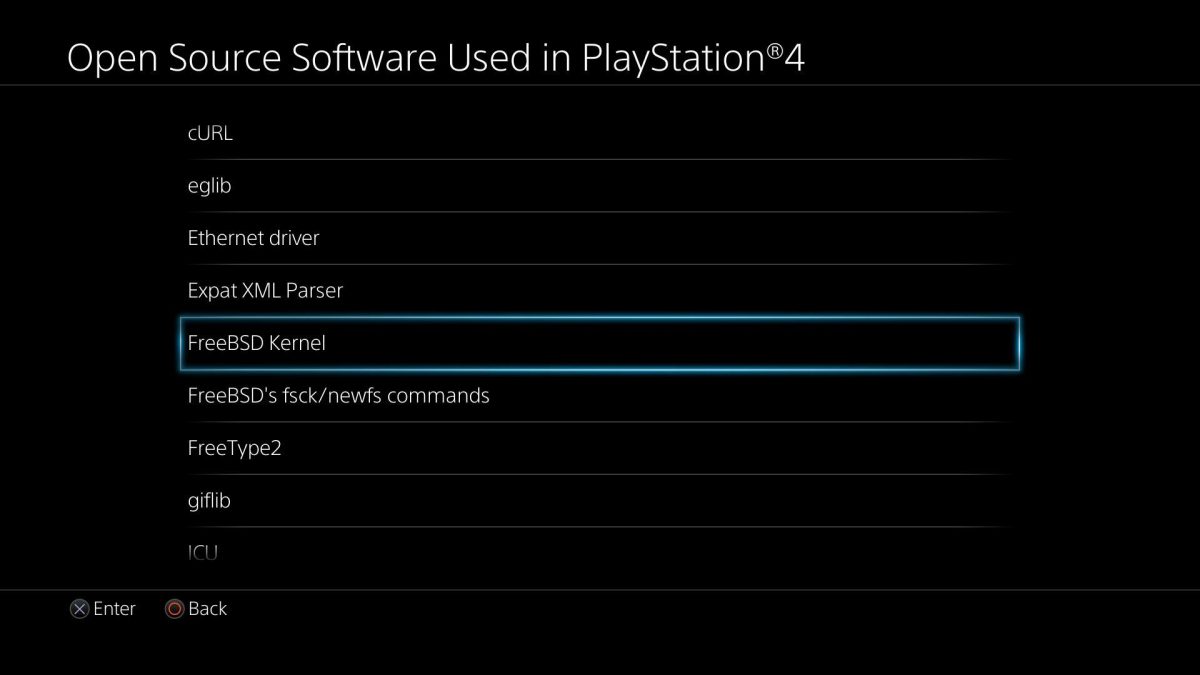

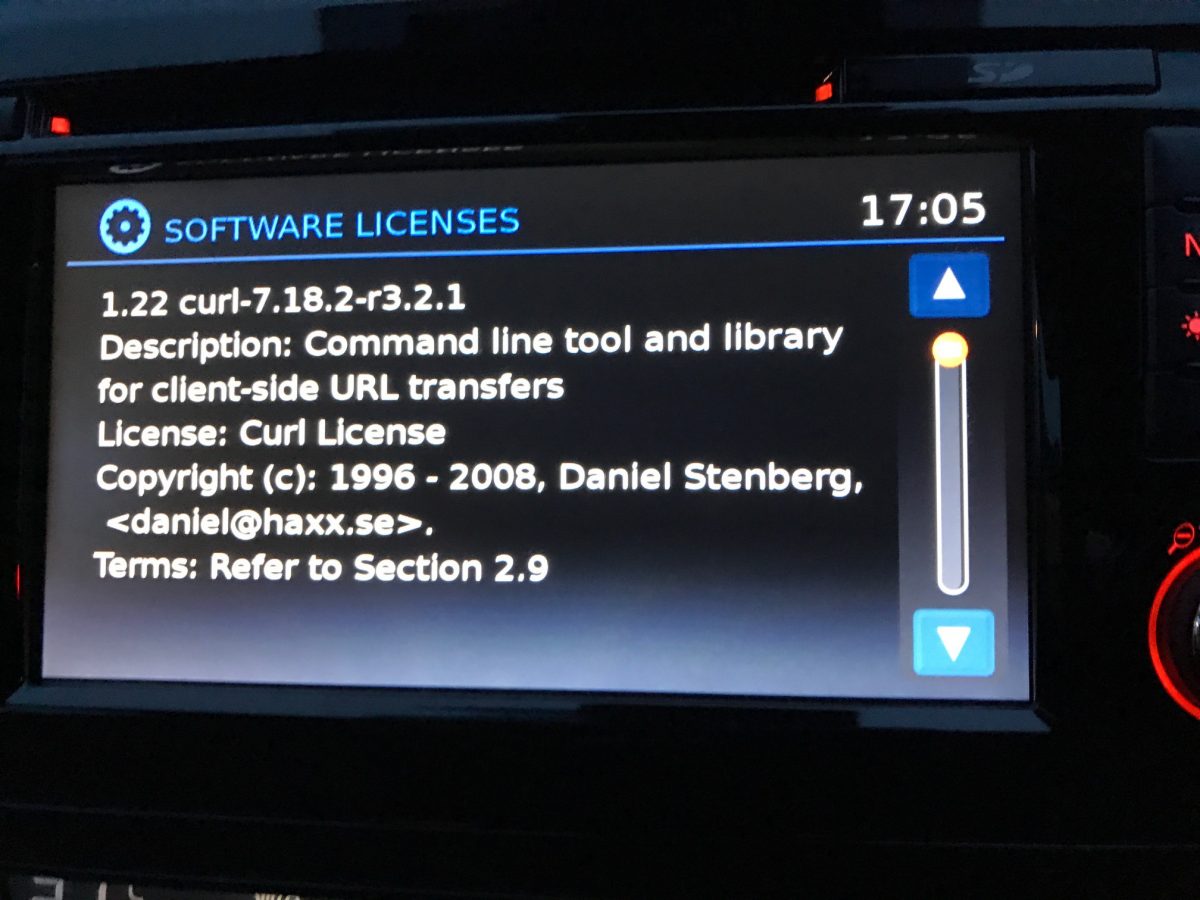

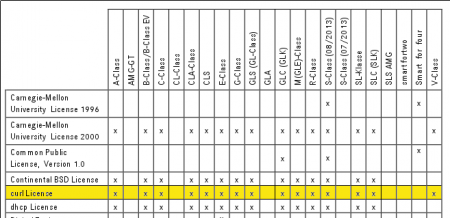

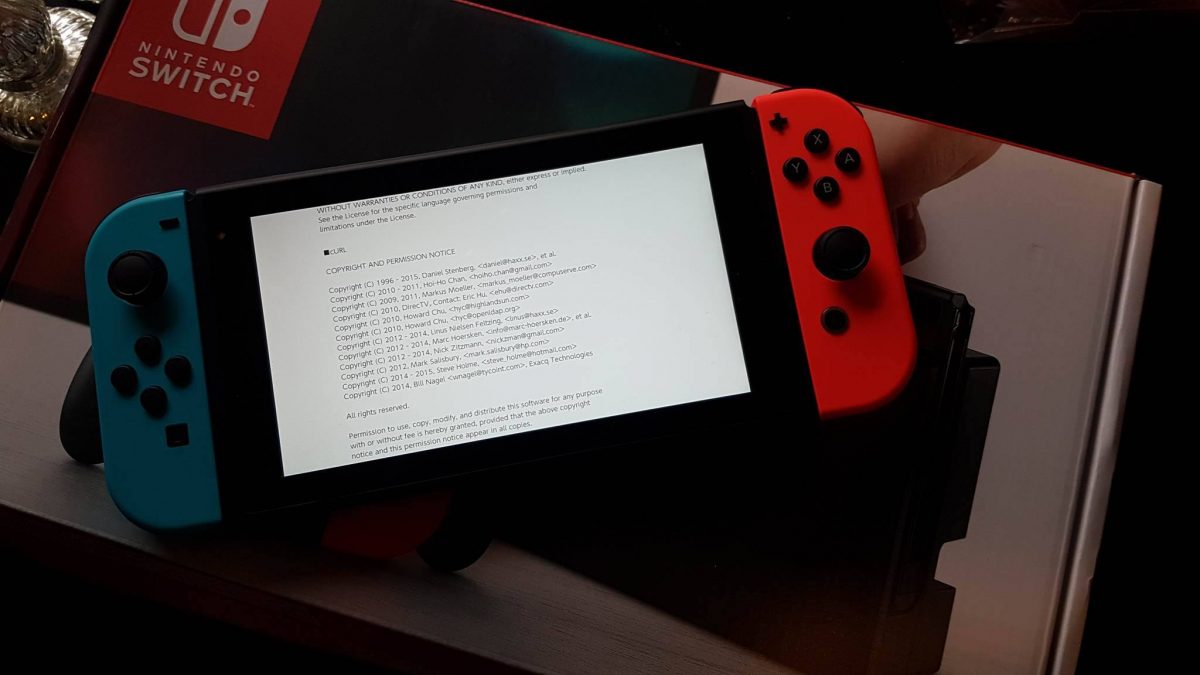

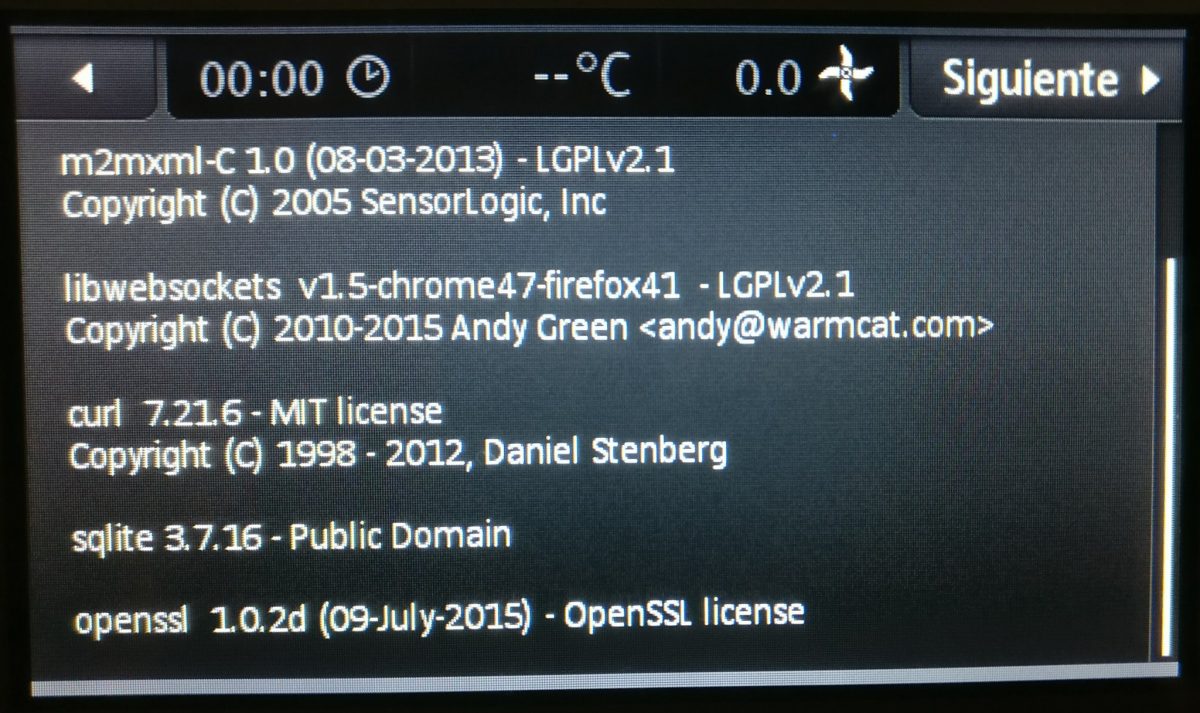

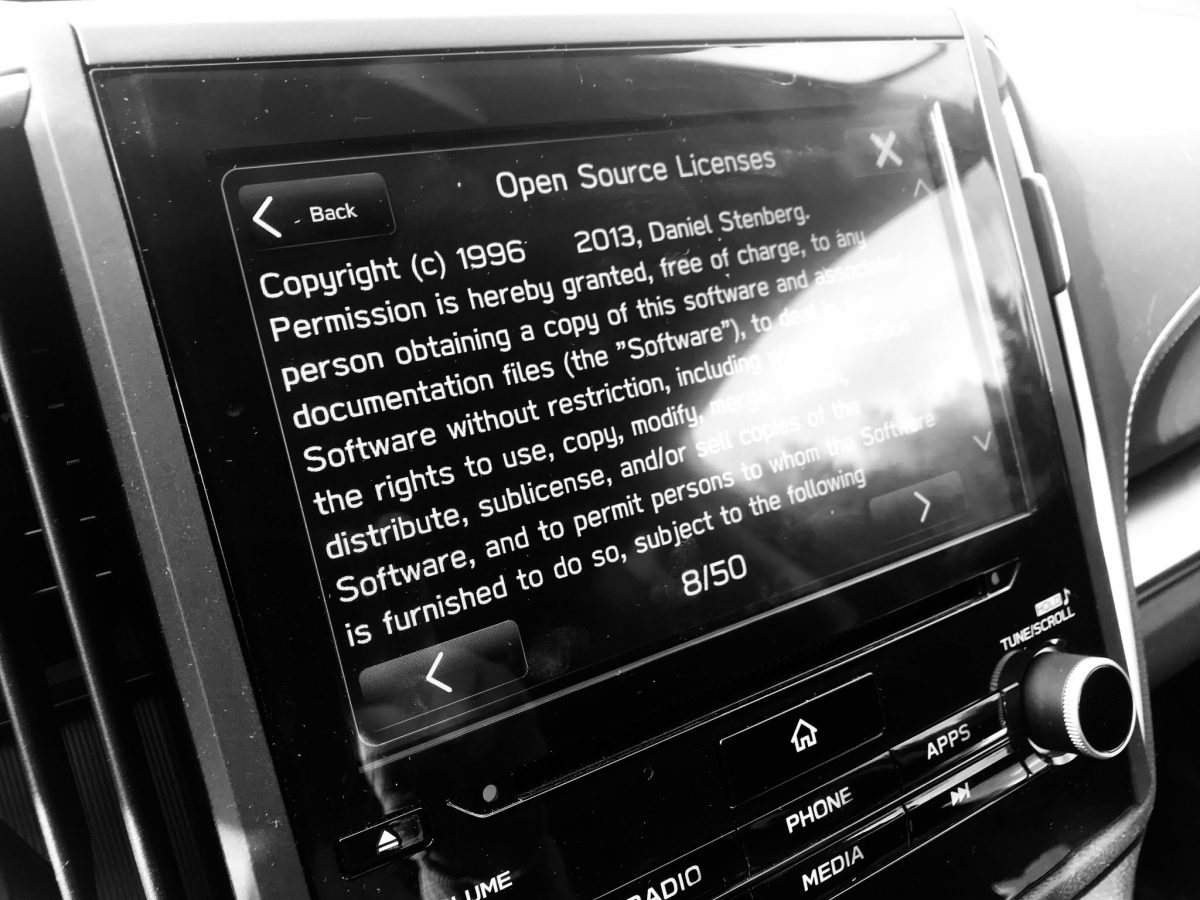

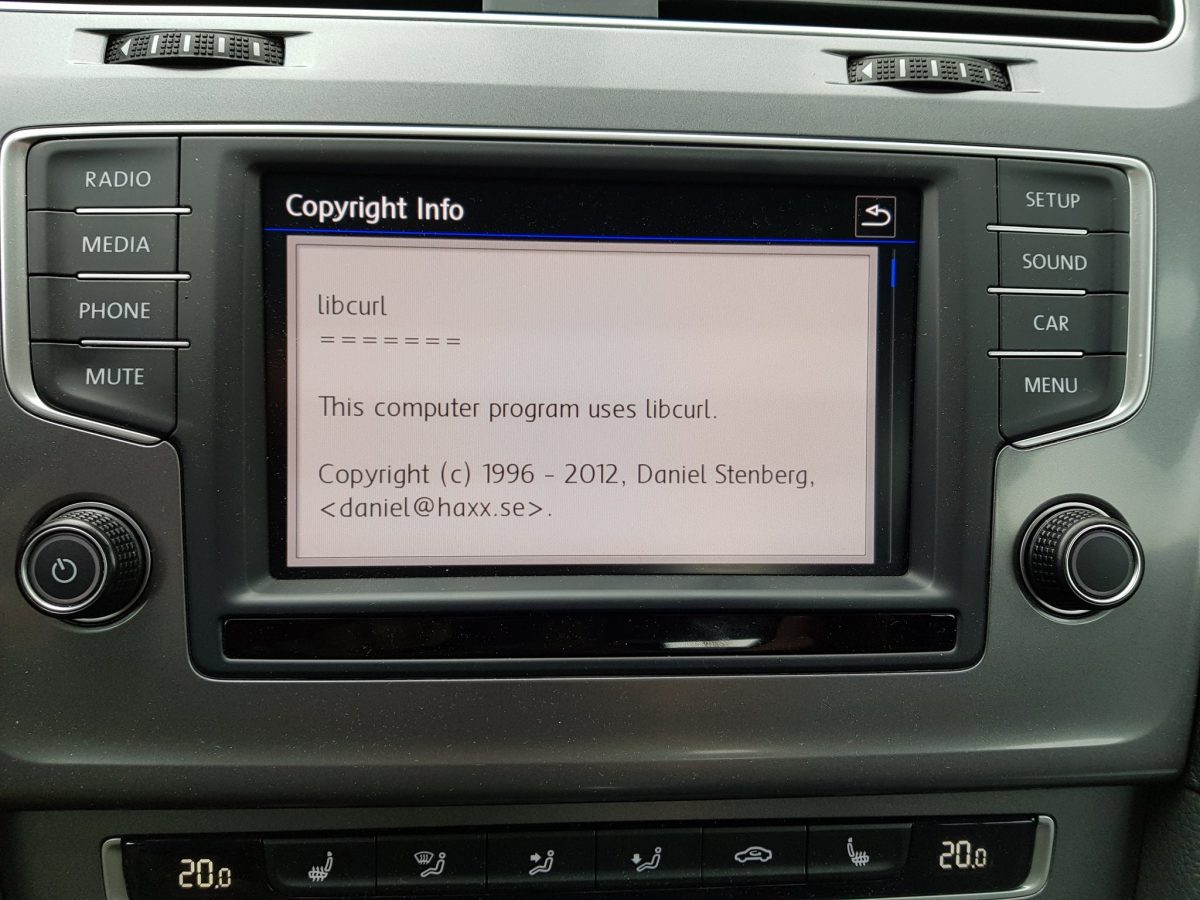

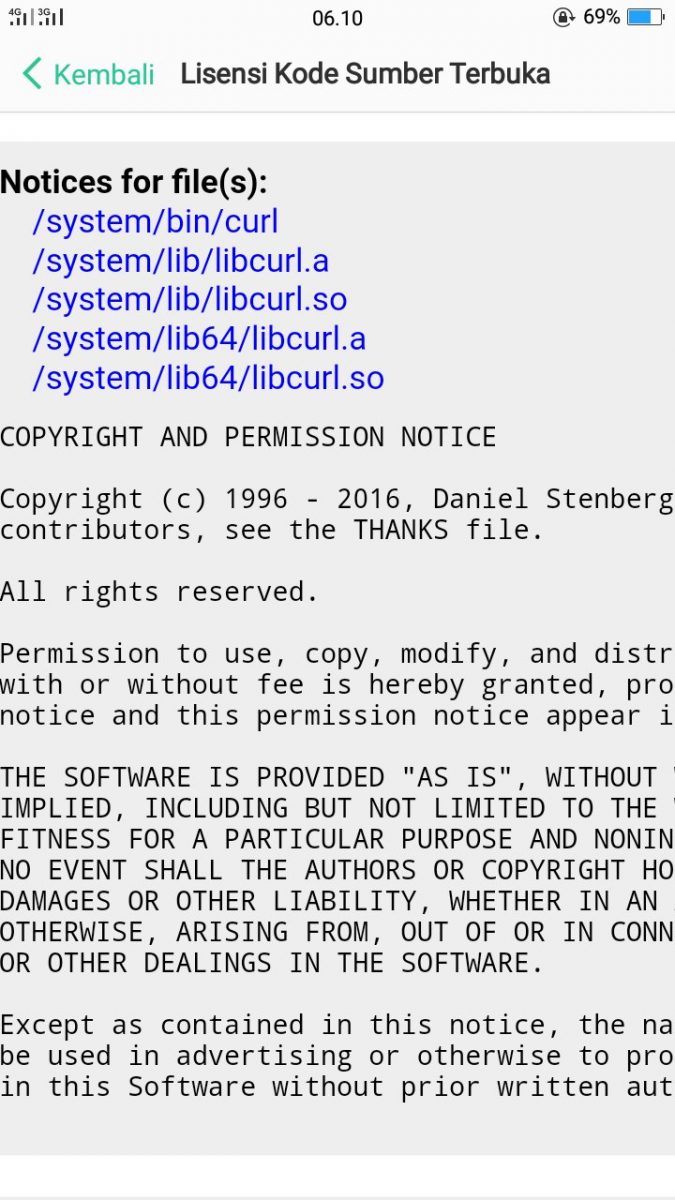

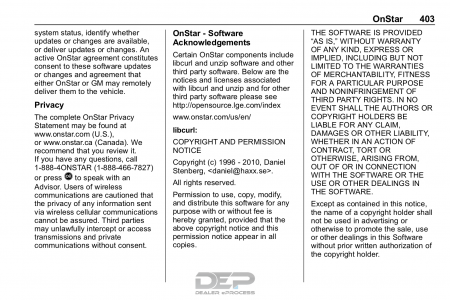

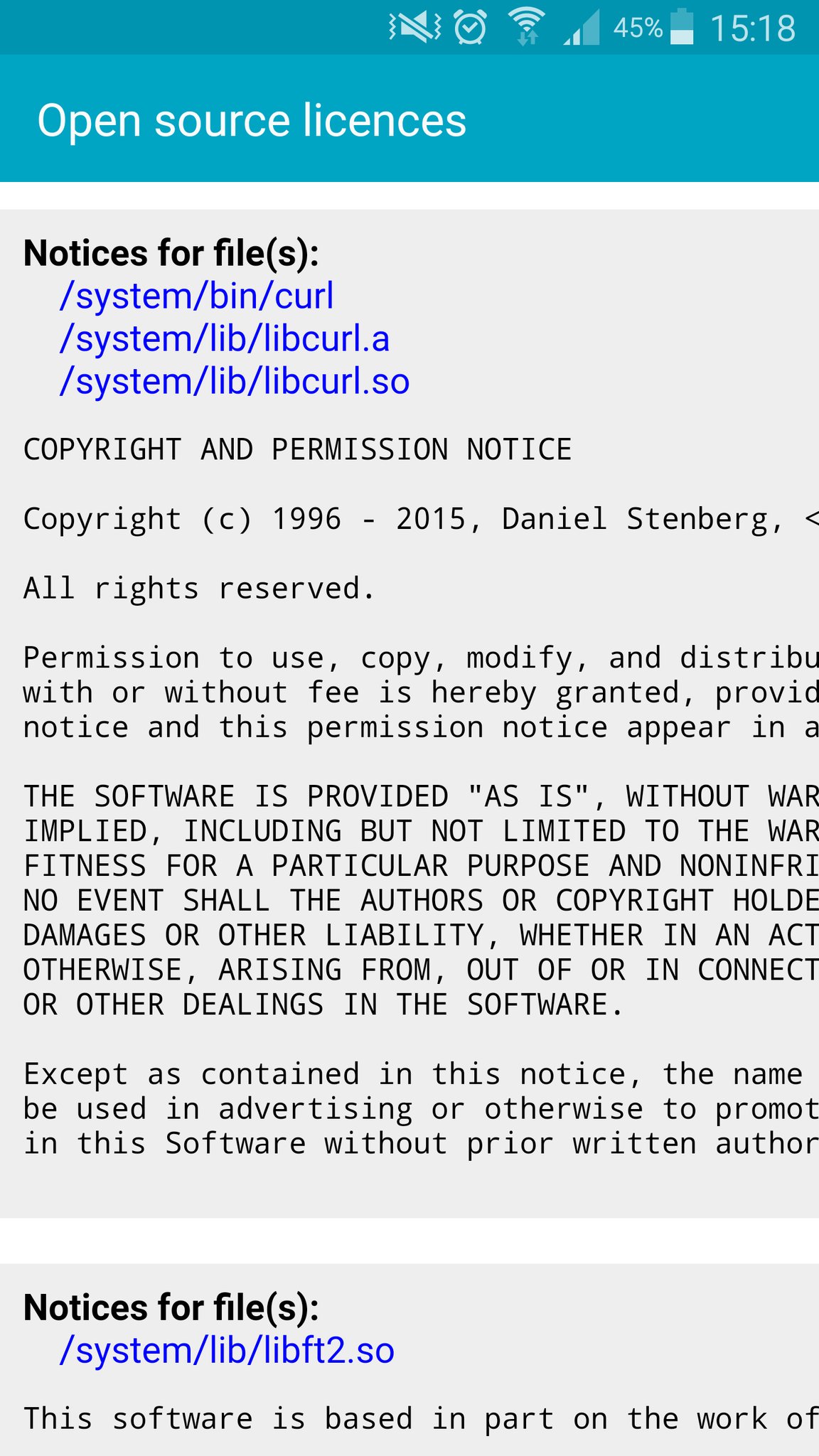

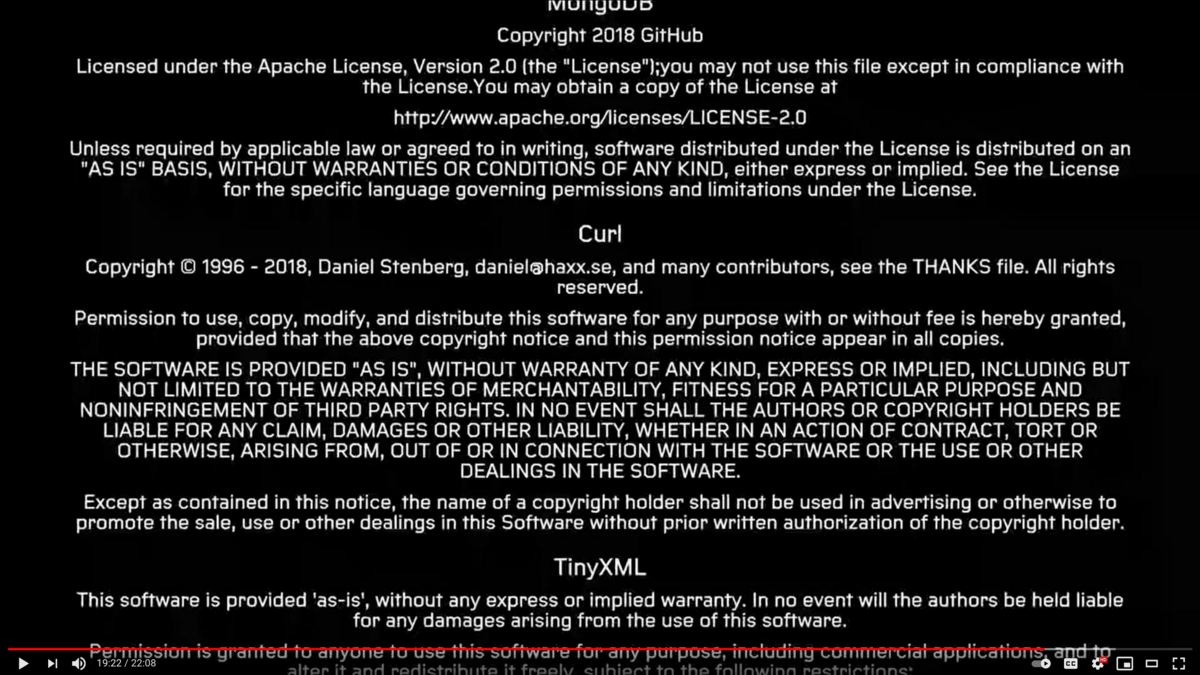

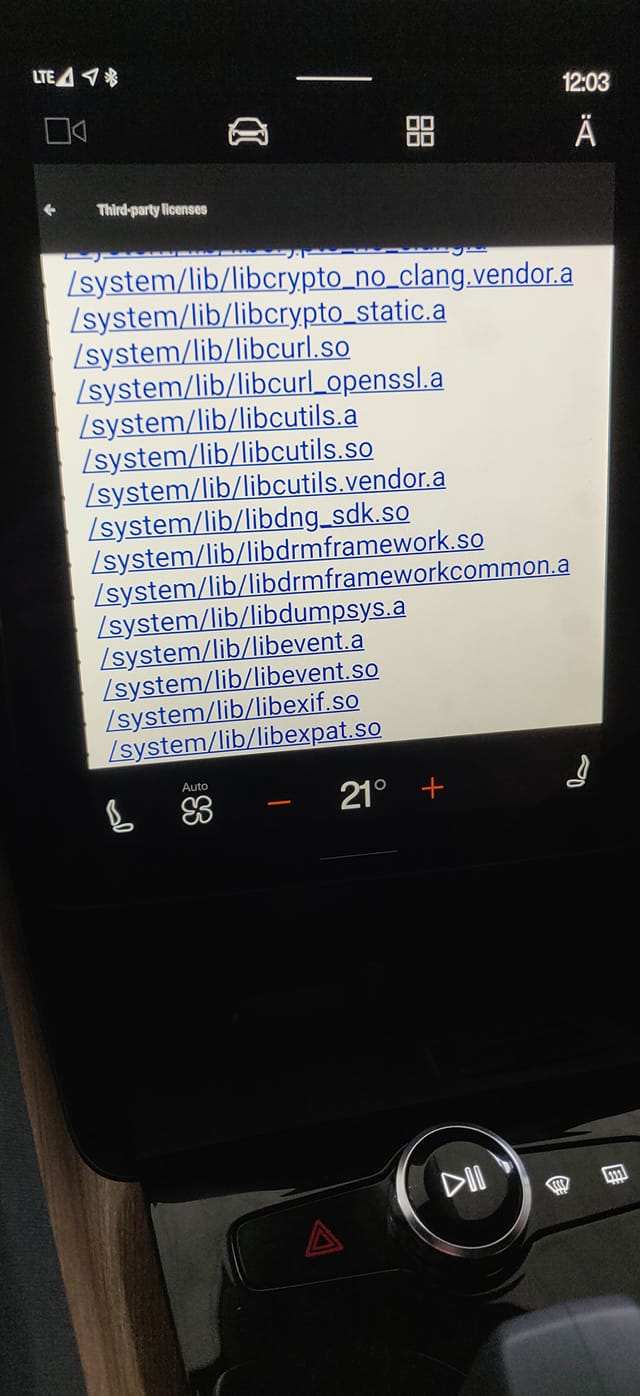

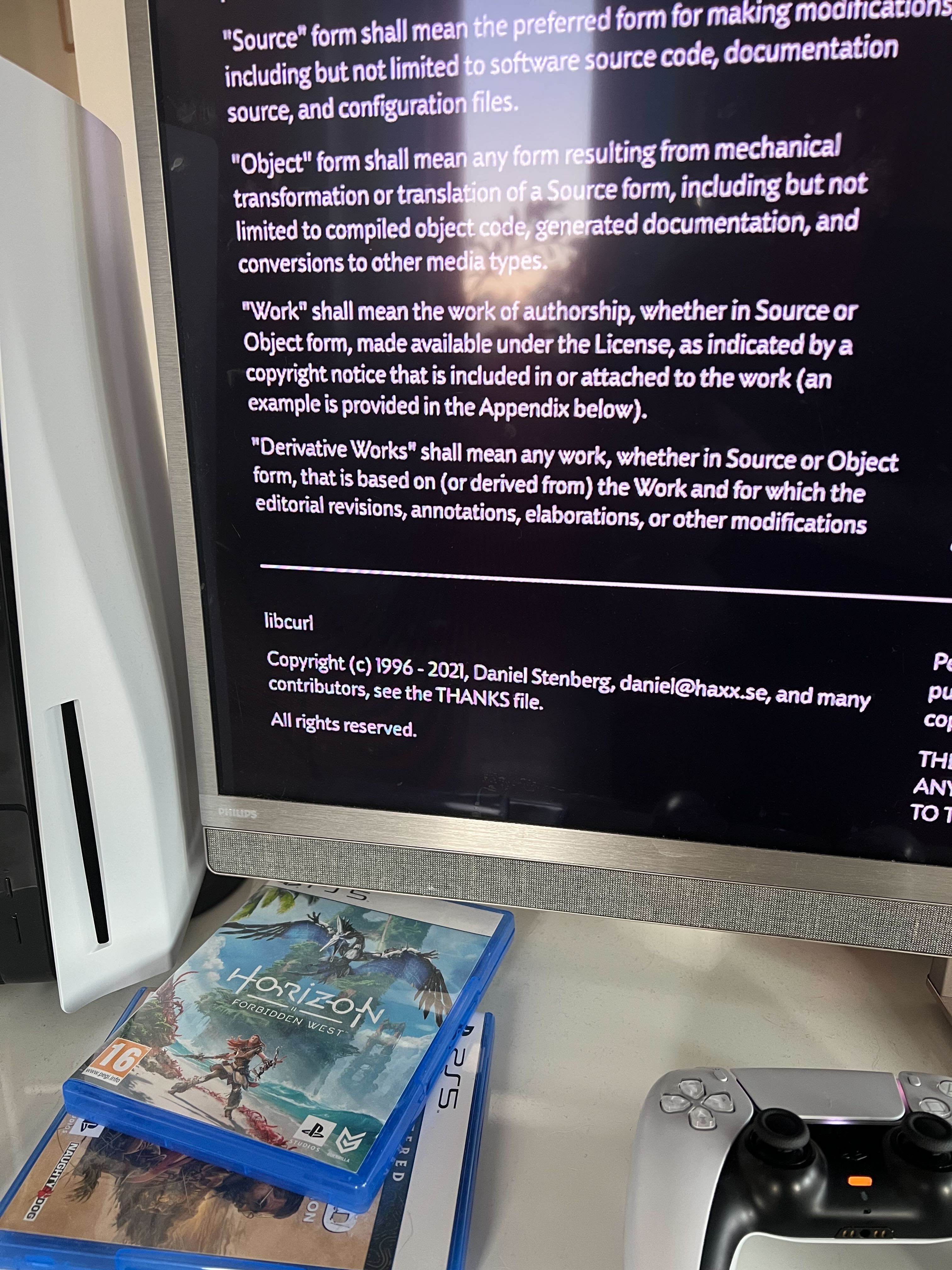

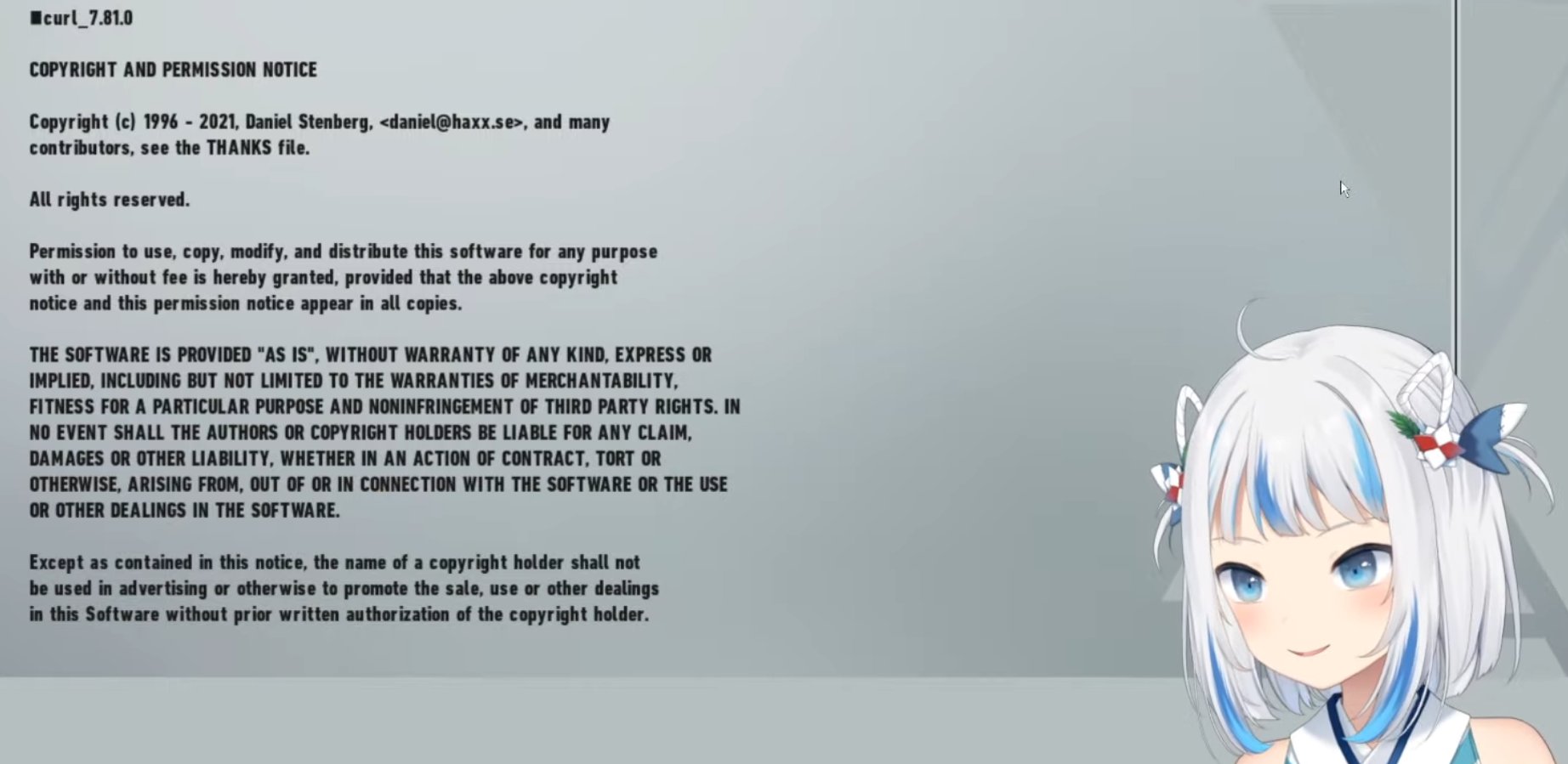

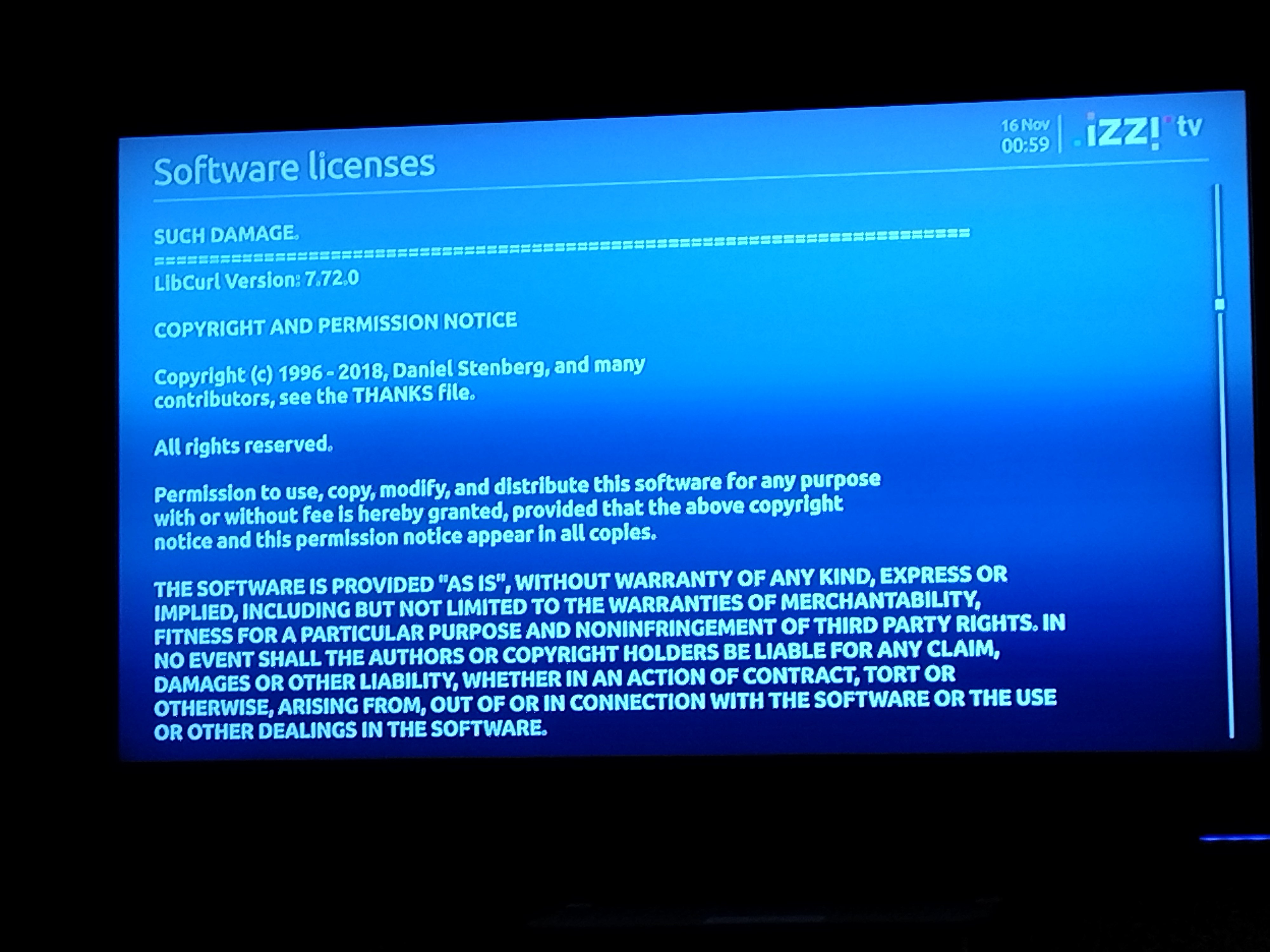

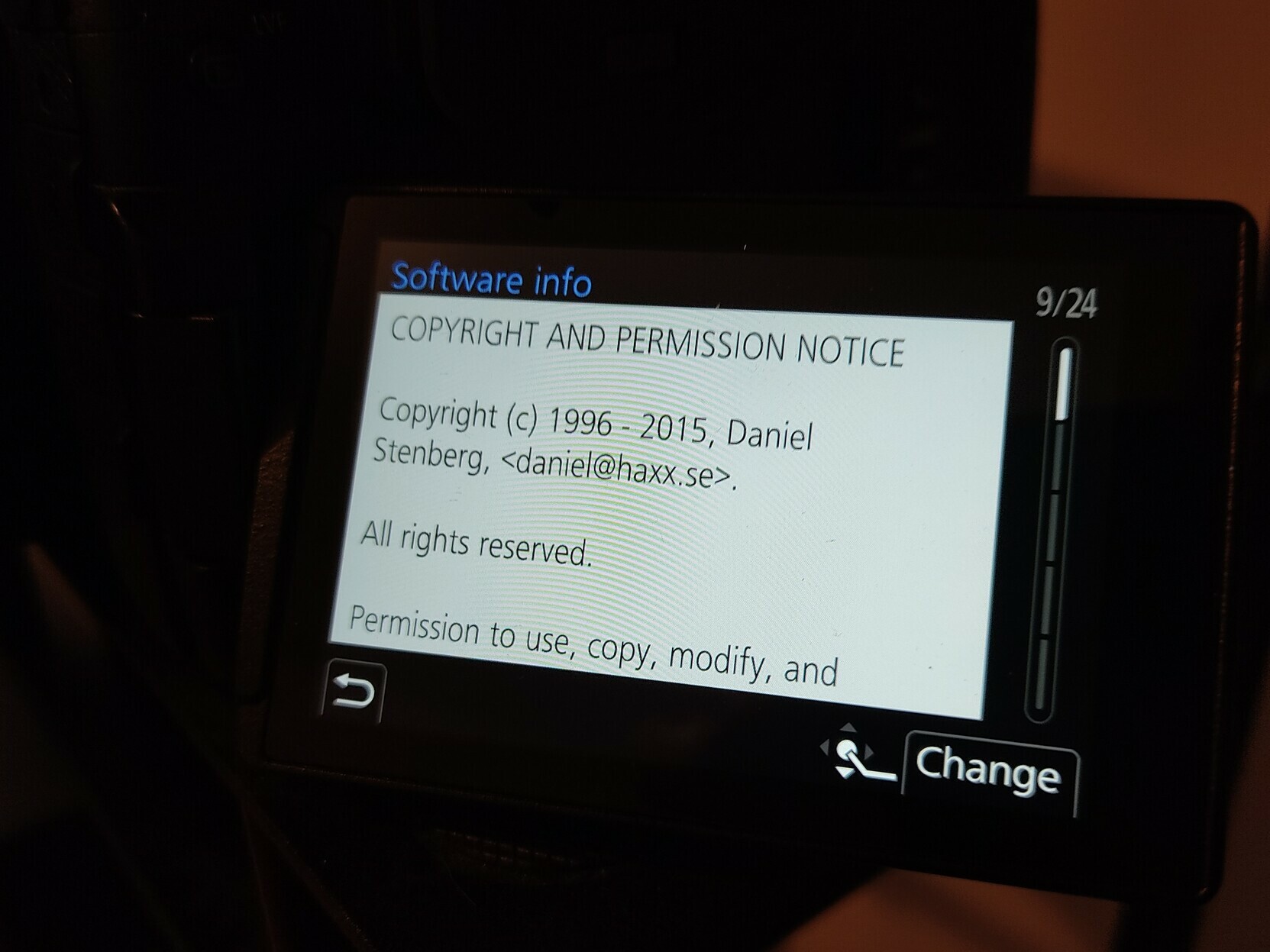

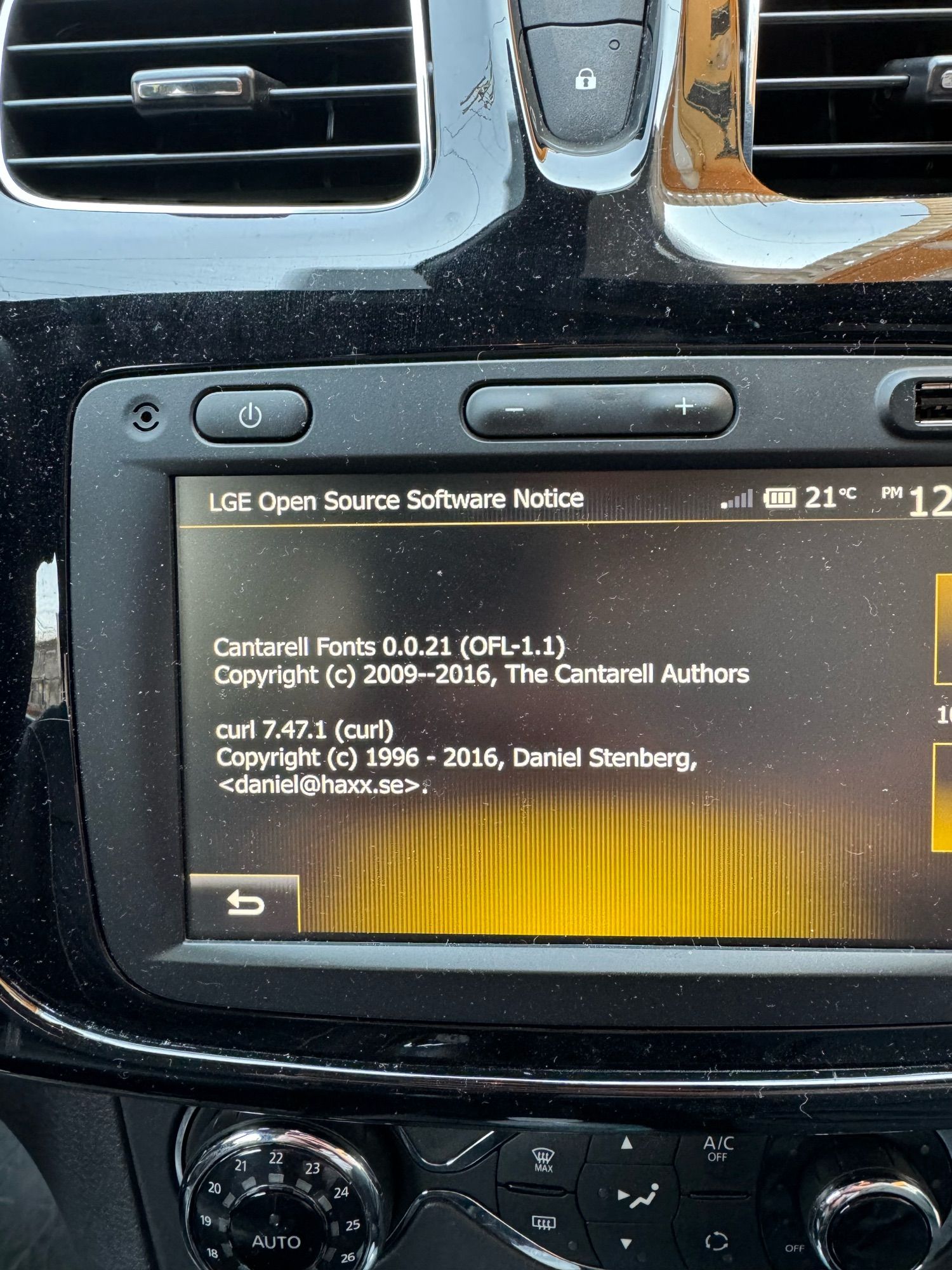

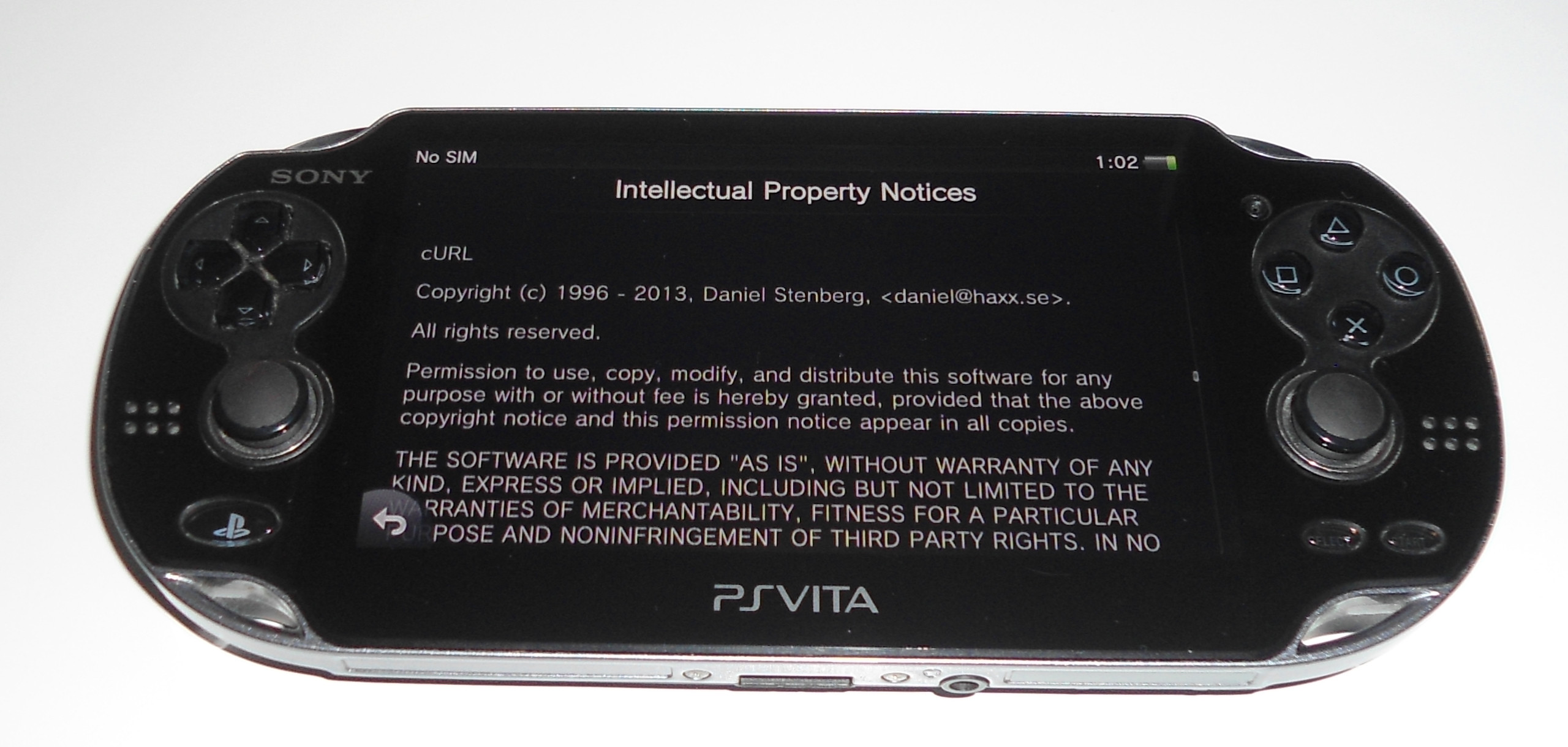

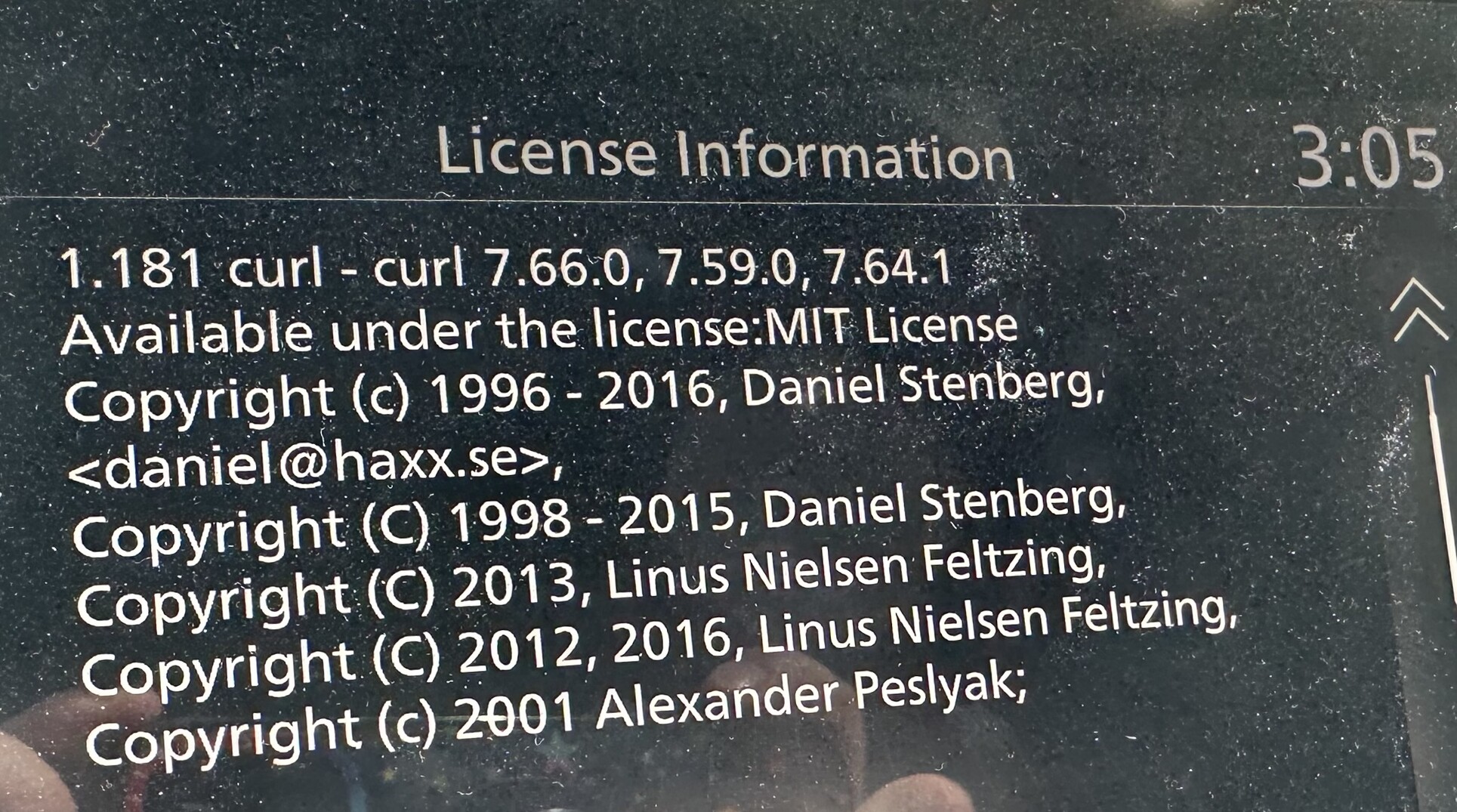

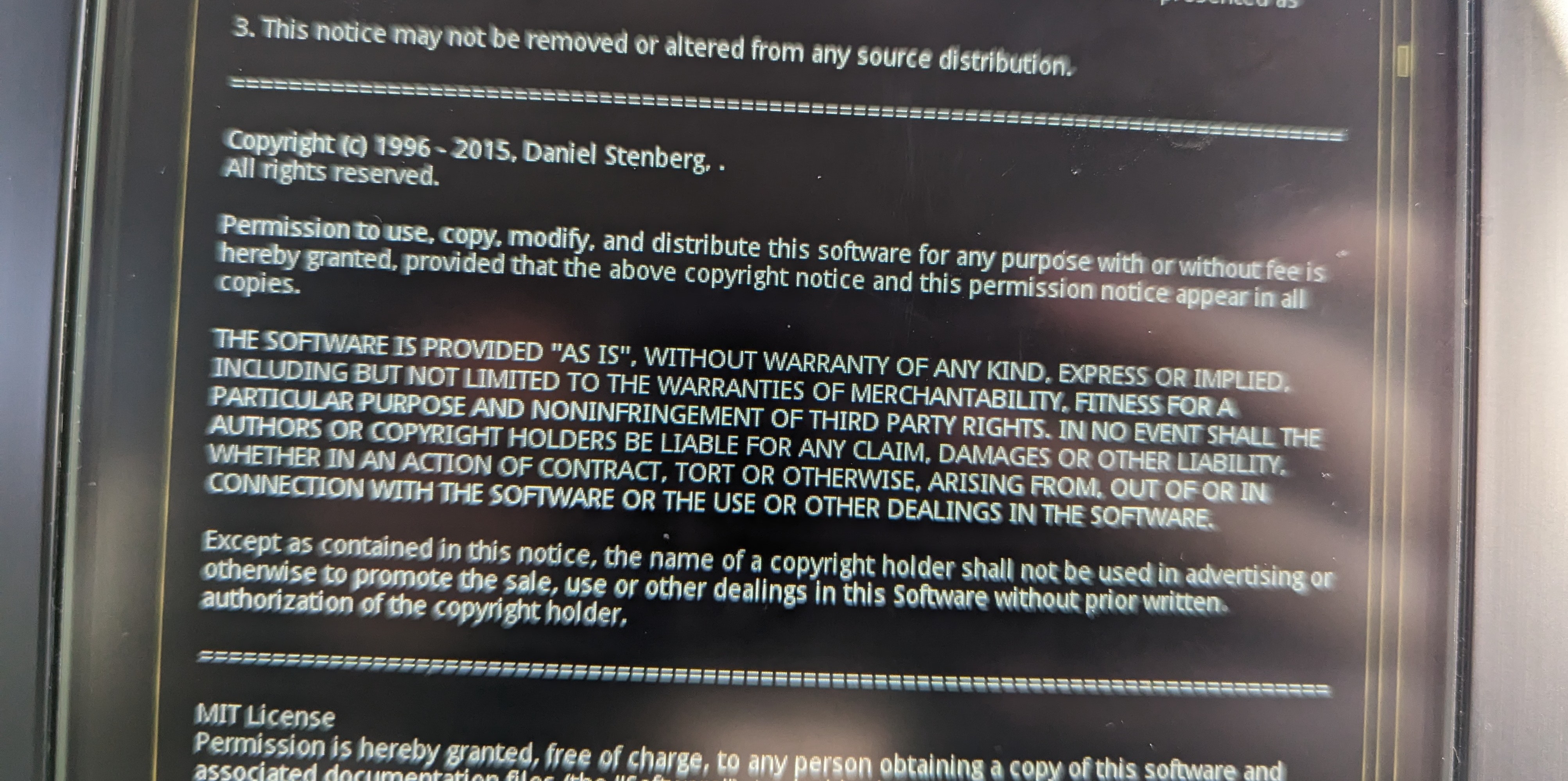

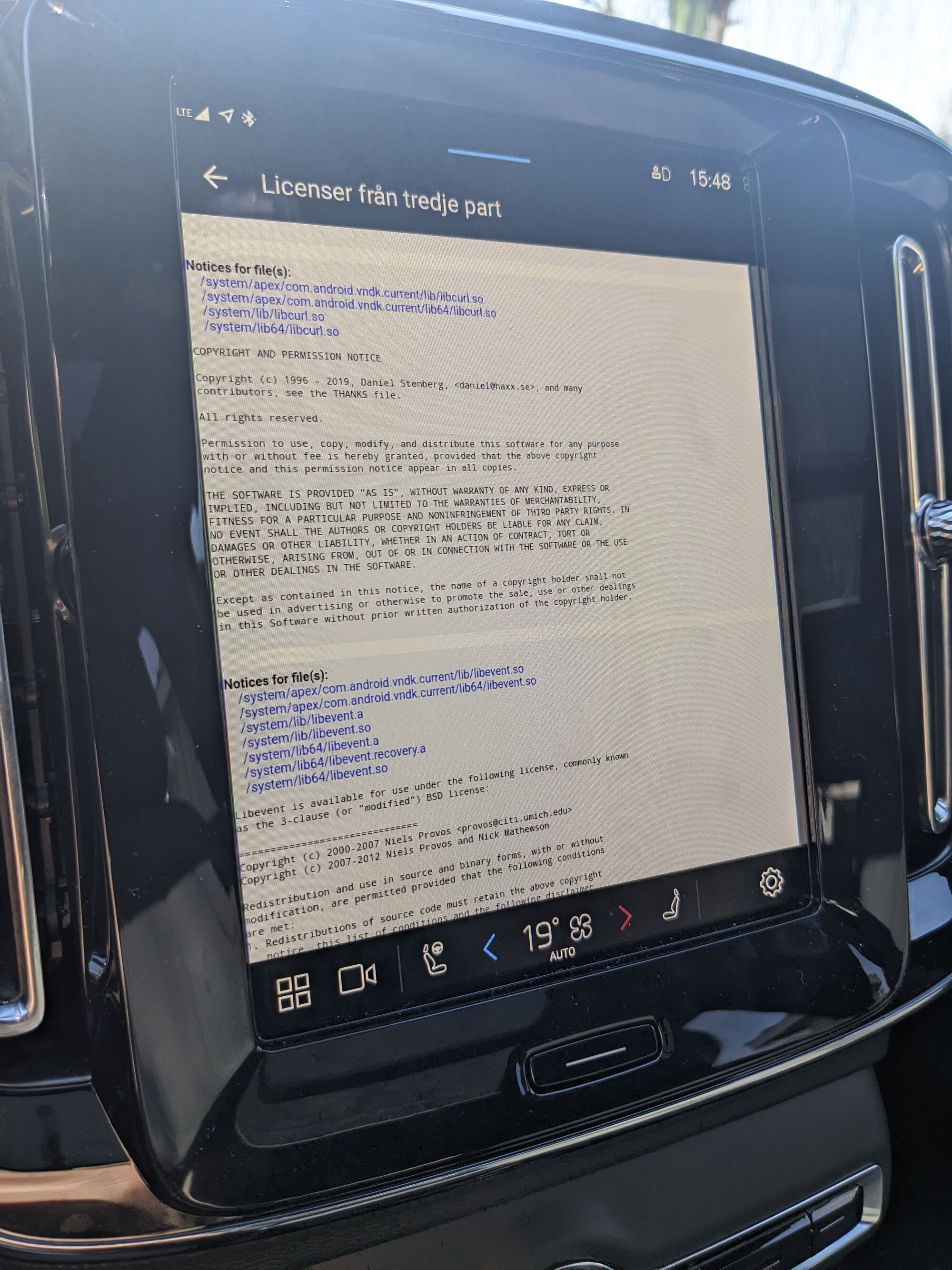

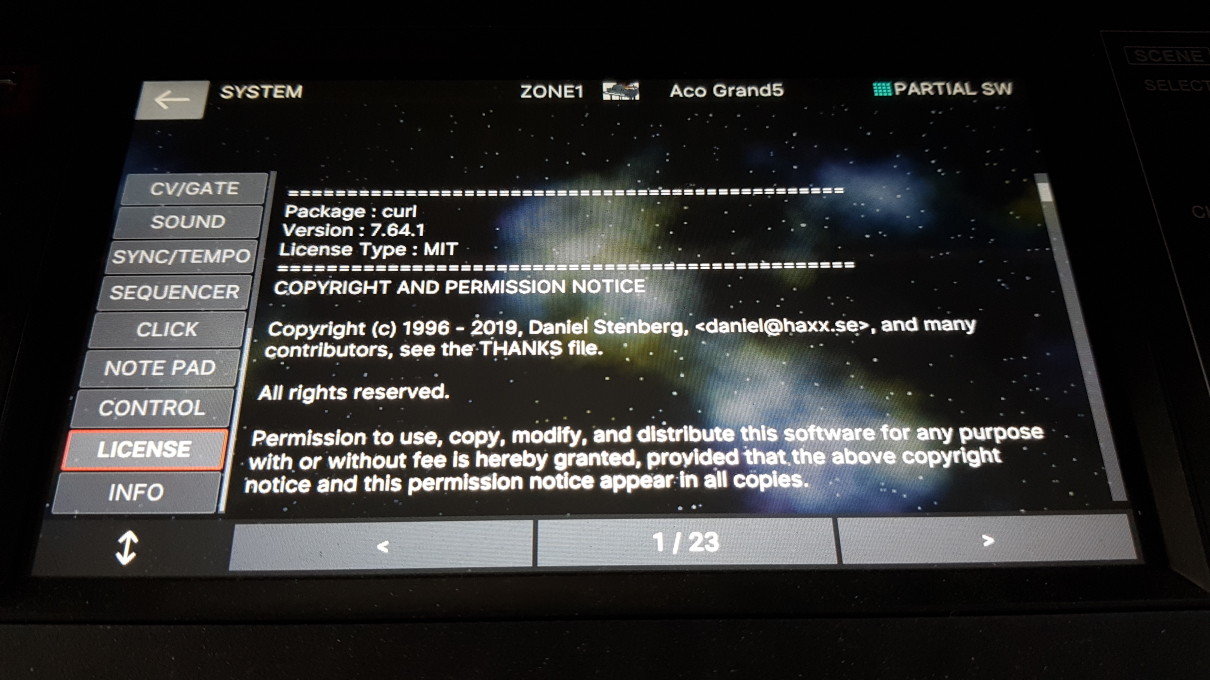

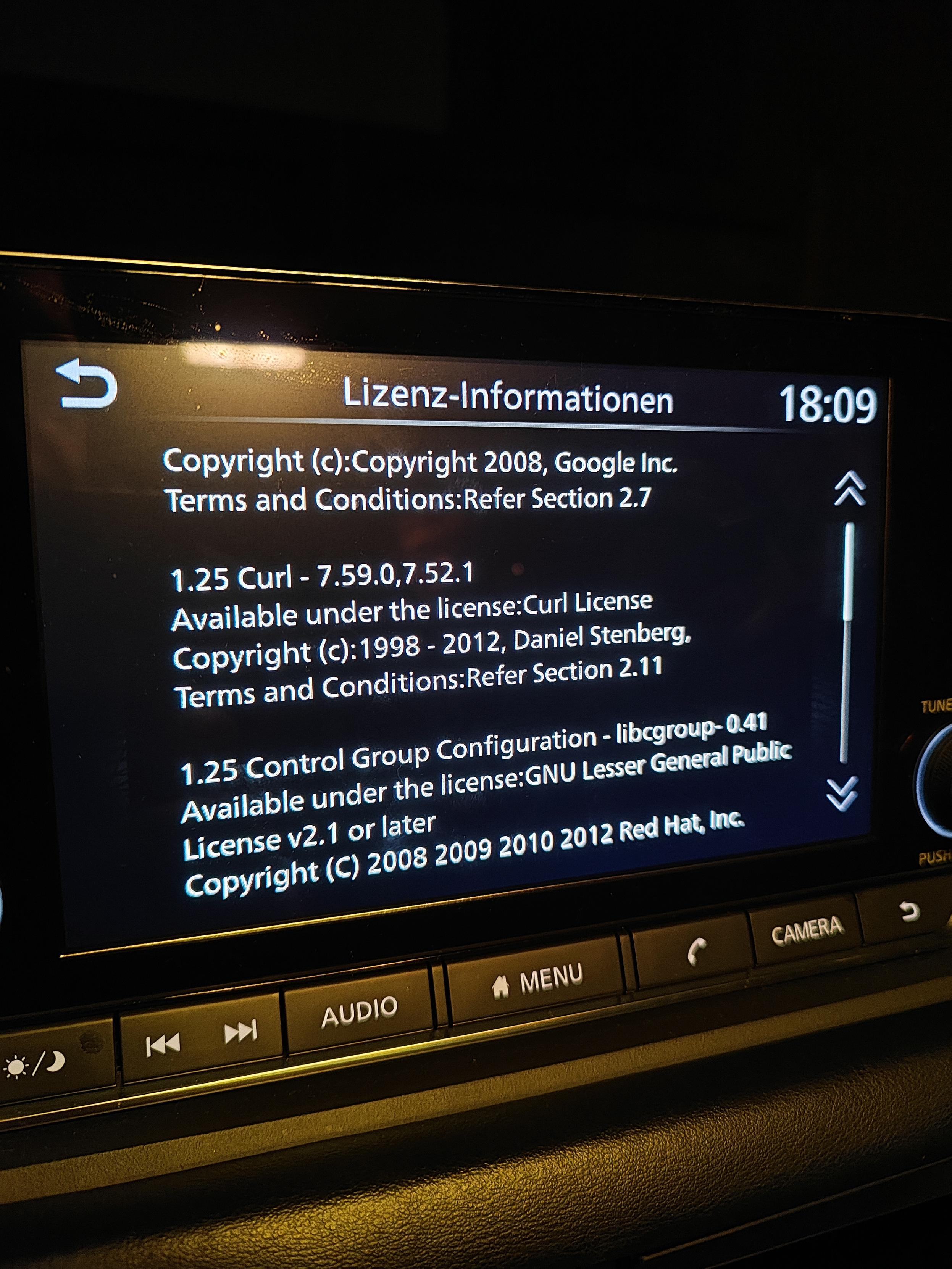

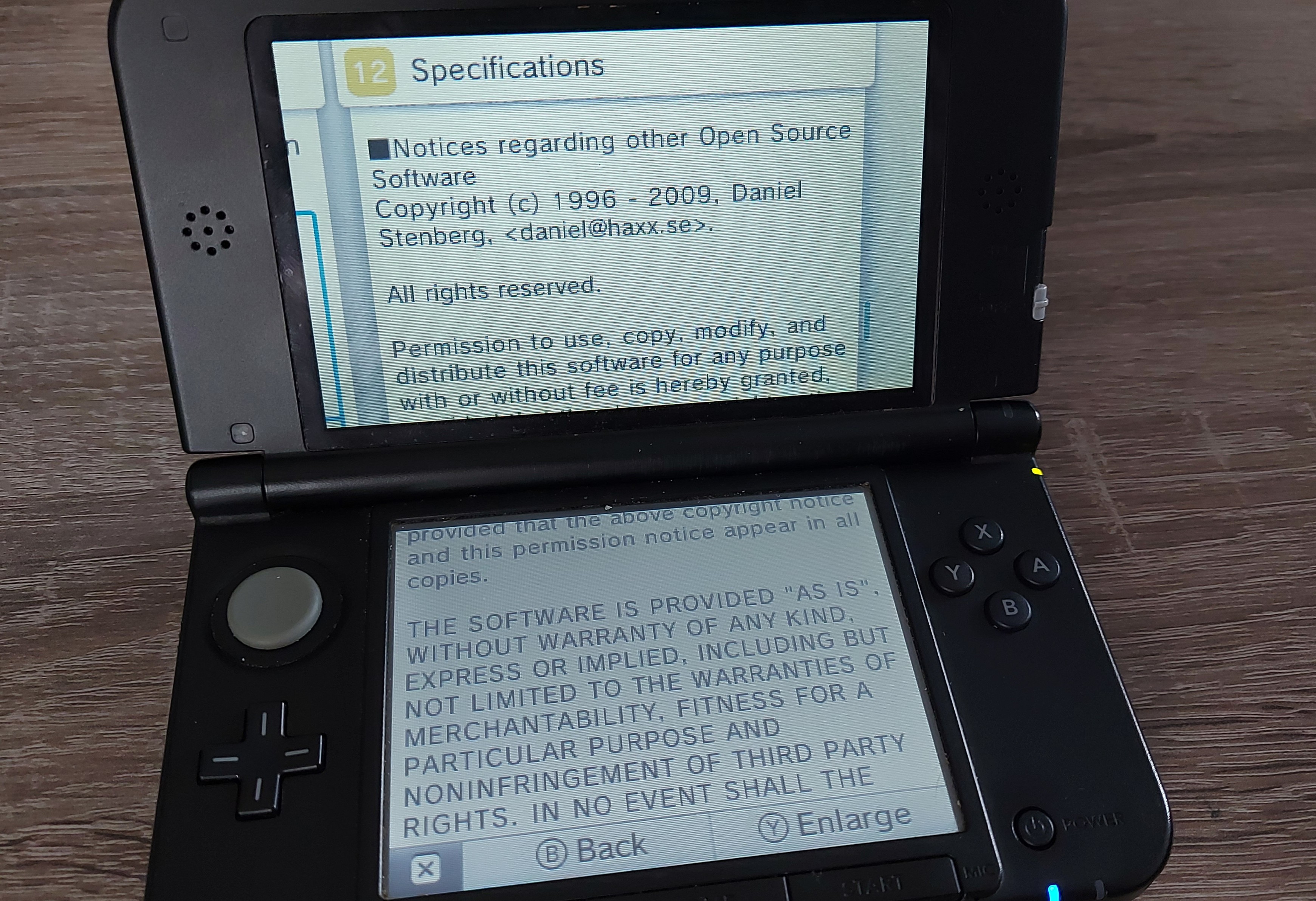

I applied for the security audit because I feel that we’ve had some security related issues lately and I’ve had the feeling that we might be missing something so it would be really good to get some experts’ eyes on the code. Also, as curl is one of the most used software components in the world a serious problem in curl could have a serious impact on tools, devices and applications everywhere. We don’t want that to happen.

I applied for the security audit because I feel that we’ve had some security related issues lately and I’ve had the feeling that we might be missing something so it would be really good to get some experts’ eyes on the code. Also, as curl is one of the most used software components in the world a serious problem in curl could have a serious impact on tools, devices and applications everywhere. We don’t want that to happen.

Scans and tests and all

We run static analyzers on the code frequently with a zero warnings tolerance. The daily clang-analyzer scan hasn’t found a problem in a long time and the Coverity once-every-few-weeks occasionally finds something suspicious but we always fix those immediately.

We have thousands of tests and unit tests that we run non-stop on the code on multiple platforms running multiple build combinations. We also use valgrind when running tests to verify memory use and check for potential memory leaks.

Secrecy

The audit itself. The report and the work on fixing the issues were all done on closed mailing lists without revealing to the world what was really going on. All as our fine security process describes.

There are several downsides with fixing things secretly. One of the primary ones is that we get much fewer eyes on the fixes and there aren’t that many people involved when discussing solutions or approaches to the issues at hand. Another is that our test infrastructure is made for and runs only public code so the code can’t really be fully tested until it is merged into the public git repository.

The report

We got the report on September 23, 2016 and it certainly gave us a lot of work.

The audit report has now been made public and is a very interesting work if you’re into security, C code and curl hacking. I find the report very clear, well written and it spells out each problem very accurately and even shows proof of concept code snippets and exploit examples to drive the points home.

Quoted from the report intro:

As for the approach, the test was rooted in the public availability of the source code belonging to the cURL software and the investigation involved five testers of the Cure53 team. The tool was tested over the course of twenty days in August and September of 2016 and main efforts were focused on examining cURL 7.50.1. and later versions of cURL. It has to be noted that rather than employ fuzzing or similar approaches to validate the robustness of the build of the application and library, the latter goal was pursued through a classic source code audit. Sources covering authentication, various protocols, and, partly, SSL/TLS, were analyzed in considerable detail. A rationale behind this type of scoping pointed to these parts of the cURL tool that were most likely to be prone and exposed to real-life attack scenarios. Rounding up the methodology of the classic code audit, Cure53 benefited from certain tools, which included ASAN targeted with detecting memory errors, as well as Helgrind, which was tasked with pinpointing synchronization errors with the threading model.

They identified no less than twenty-three (23) potential problems in the code, out of which nine were deemed security vulnerabilities. But I’d also like to emphasize that they did also actually say this:

At the same time, the overall impression of the state of security and robustness of the cURL library was positive.

Resolving problems

In the curl security team we decided to downgrade one of the 9 vulnerabilities to a “plain bug” since the required attack scenario was very complicated and the risk deemed small, and two of the issues we squashed into treating them as a single one. That left us with 7 security vulnerabilities. Whoa, that’s a lot. The largest amount we’ve ever fixed in a single release before was 4.

I consider handling security issues in the project to be one of my most important tasks; pretty much all other jobs are down-prioritized in comparison. So with a large queue of security work, a lot of bug fixing and work on features basically had to halt.

You can get a fairly detailed description of our work on fixing the issues in the fix and validation log. The report, the log and the advisories we’ve already posted should cover enough details about these problems and associated fixes that I don’t feel a need to write about them much further.

More problems

Just because we got our hands full with an audit report doesn’t mean that the world stops, right? While working on the issues one by one to have them fixed we also ended up getting an additional 4 security issues to add to the set, by three independent individuals.

All these issues gave me a really busy period and it felt great when we finally shipped 7.51.0 and announced all those eleven fixes to the world and I could get a short period of relief until the next tsunami hits.

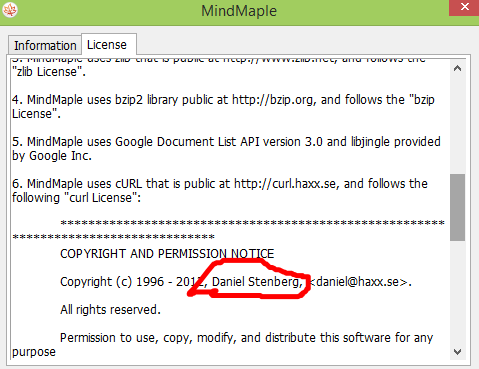

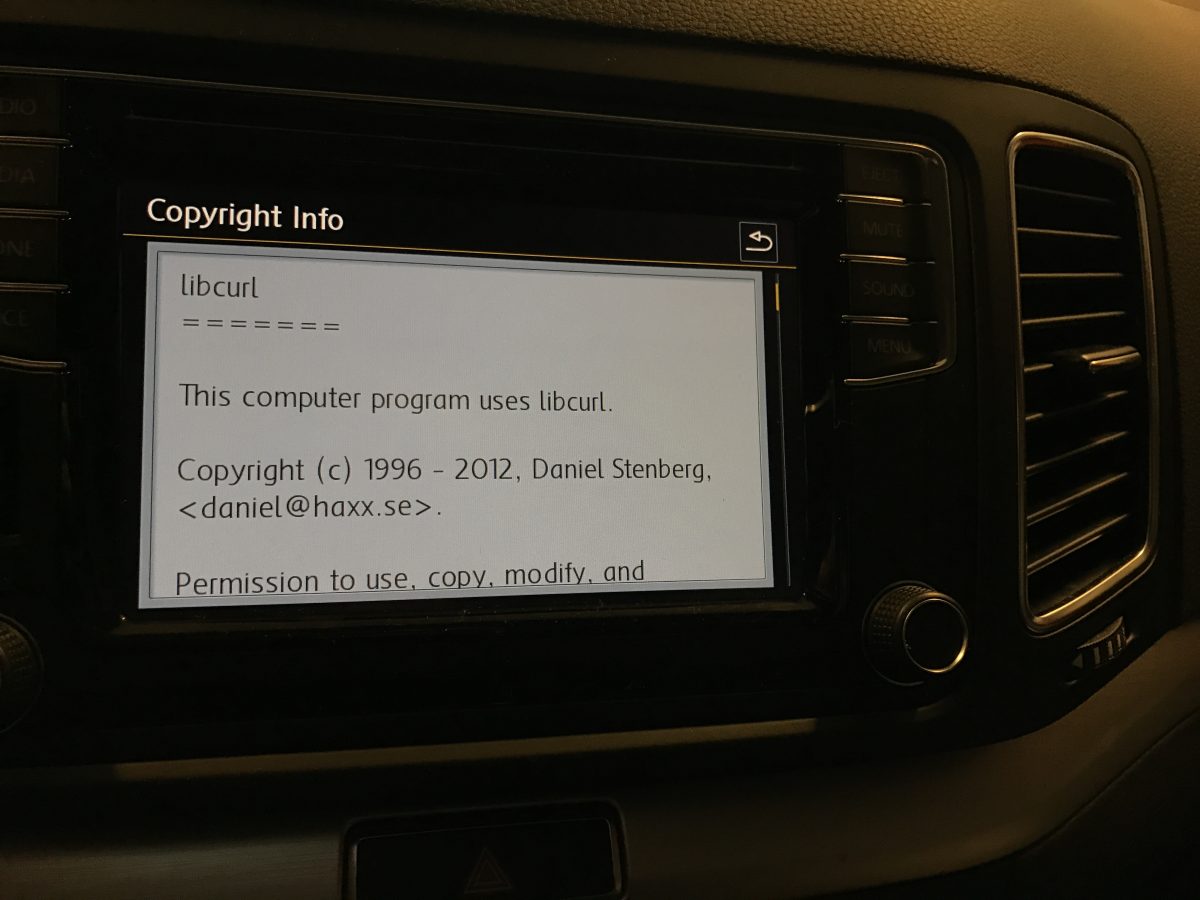

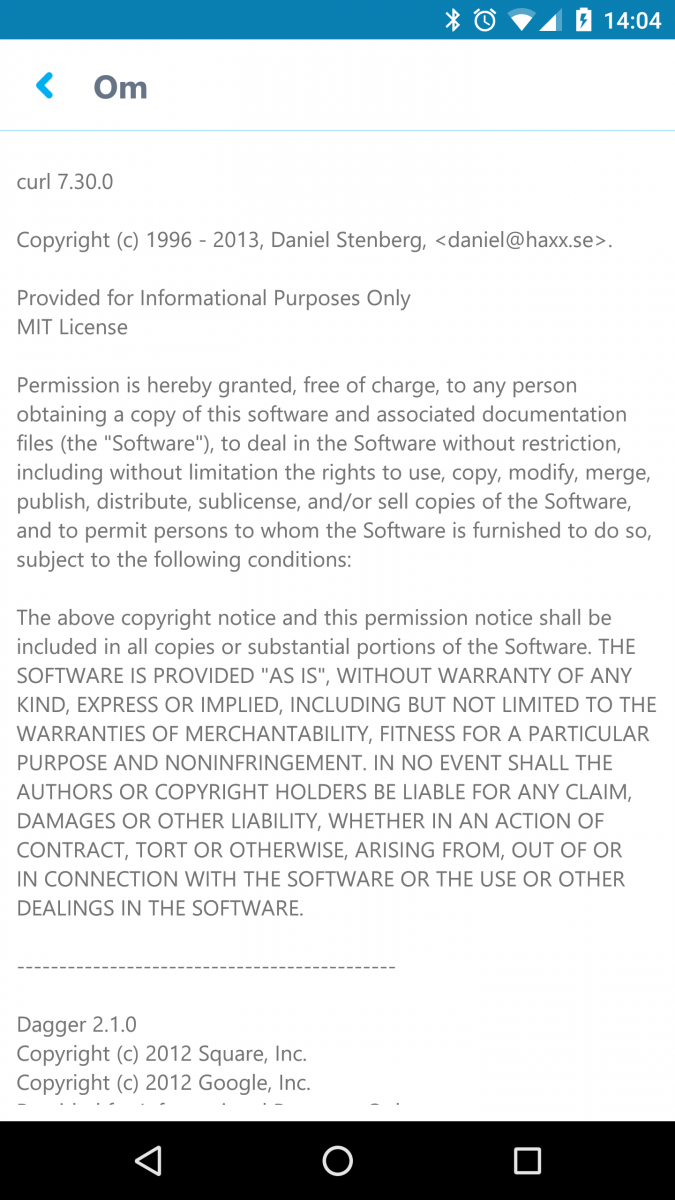

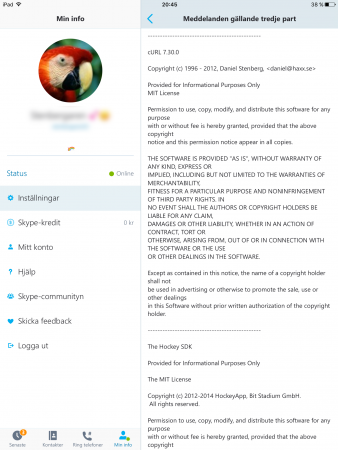

The main effect is that normal end users find my email address via the

The main effect is that normal end users find my email address via the  shed at the end of October 2016.

shed at the end of October 2016.