tldr: we’ve made curl handle dates beyond 2038 better on systems with 32 bit longs.

libcurl is very portable and is built and used on virtually all current widely used operating systems that run on 32bit or larger architectures (and on a fair amount of not so widely used ones as well).

This offers some challenges. Keeping the code stellar and working on as many platforms as possible at the same time is hard work.

How long is a long?

The C variable type “long” has existed since the dawn of time and used to be 32 bit big already back in the days most systems were 32 bits. With the introduction of 64 bit systems in the 1990s, something went wrong and when most operating systems went with 64 bit longs, some took the odd route and stuck with a 32 bit long… The windows world even chose to not support “long long” for 64 bit types but instead it insists on calling them “__int64”!

(Thankfully, ints have at least remained 32 bit!)

Two less clever API decisions

Back in the days when humans still lived in caves, we decided for the libcurl API to use ‘long’ for a whole range of function arguments. In hindsight, that was naive and not too bright. (I say “we” to make it less obvious that it of course is mostly me who’s to blame for this.)

Another less clever design idea was to use vararg functions to set (all) options. This is convenient in the way we have one function to set a huge amount of different option, but it is also quirky and error-prone because when you pass on a numeric expression in C it typically gets sent as an ‘int’ unless you tell it otherwise. So on systems with differently sized ints vs longs, it is destined to cause some mistakes that, thanks to use of varargs, the compiler can’t really help us detect! (We actually have a gcc-only hack that provides type-checking even for the varargs functions, but it is not portable.)

libcurl has both an option to pass time to libcurl using a long (CURLOPT_TIMEVALUE) and an option to extract a time from libcurl using a long (CURLINFO_FILETIME).

We stick to using our “not too bright” API for stability and compatibility. We deem it to be even more work and trouble for us and our users to change to another API rather than to work and live with the existing downsides.

Time may exist after 2038

There’s also this movement to transition the time_t variable type from 32 to 64 bit. time_t of course being the preferred type for C and C++ programs to store timestamps in. It is the number of seconds since January 1st, 1970. Sometimes called the unix epoch. A signed 32 bit time_t can be used to store timestamps with second accuracy from roughly 1903 to 2038. As more and more things will start to refer to dates after 2038, this is of course becoming a problem. We need to move to 64 bit time_t all over.

We’re now less than 20 years away from the signed 32bit tip-over point: 03:14:07 UTC, 19 January 2038.

To complicate matters even more, there are odd systems out there with unsigned time_t variables. Such systems then cannot easily refer to dates before 1970, but can instead hold dates up to the year 2106 even with just 32 bits. Oh and there are some systems with 64 bit long that feature a 32 bit time_t, and 32 bit systems with 64 bit time_t!

Most modern systems today have 64 bit time_t – including win64, and 64 bit time_t can handle dates up to about year 292,471,210,647.

int – long – time_t

- We cannot move data between ints and longs in the code and assume it doesn’t overflow

- We can’t move data losslessly between ints and time_t

- We must not move data between long and time_t

Recently we’ve been working on making sure we live up to these three rules in libcurl. One could say it was about time! (pun intended)

In particular number (3) has required us to add new entry points to the API so that even 32 bit long systems can set/read 64 bit time. Starting in libcurl 7.59.0, applications can pass 64 bit times to libcurl with CURLOPT_TIMEVALUE_LARGE and extract 64 bit times with CURLINFO_FILETIME_T. For compatibility reasons, the old versions will of course be kept around but newer applications should really consider the new options.

We also recently did an overhaul of our time and date parser (externally accessible as curl_getdate() ) which we learned erroneously used a ‘long’ in the calculation which made it not work proper beyond 2038 on systems with 32 bit longs. This fix will also ship in 7.59.0 (planned release date: March 21, 2018).

If you find anything in curl that doesn’t deal with times after 2038 correctly, please file a bug!

intend to do it again:

intend to do it again:

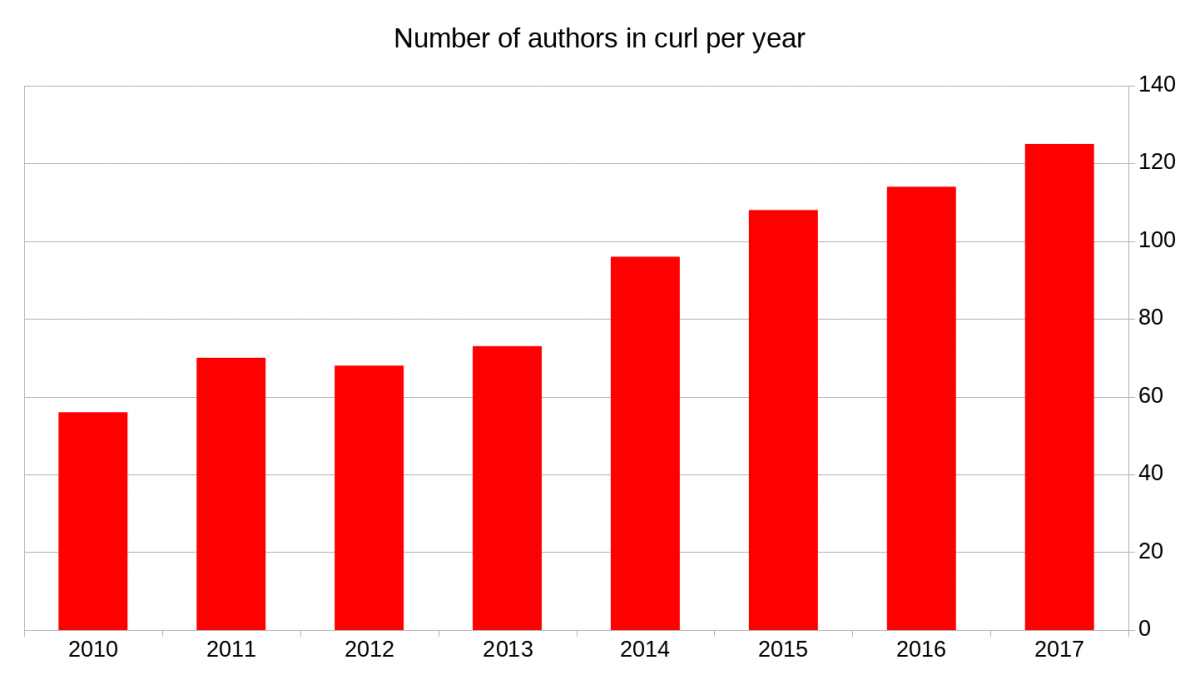

I went to London and “represented curl” in the

I went to London and “represented curl” in the