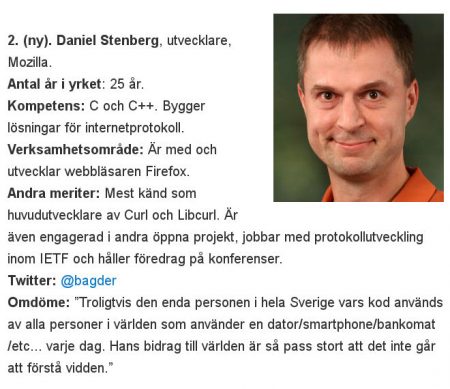

Following up on the problem with our current lack of a universal URL standard that I blogged about in May 2016: My URL isn’t your URL. I want a single, unified URL standard that we would all stand behind, support and adhere to.

What triggers me this time, is yet another issue. A friendly curl user sent me this URL:

http://user@example.com:80@daniel.haxx.se

… and pasting this URL into different tools and browsers show that there’s not a wide agreement on how this should work. Is the URL legal in the first place and if so, which host should a client contact?

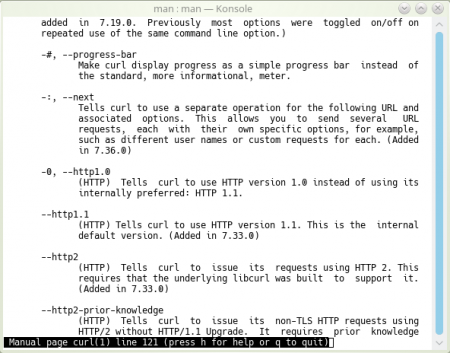

- curl treats the ‘@’-character as a separator between userinfo and host name so ‘example.com’ becomes the host name, the port number is 80 followed by rubbish that curl ignores. (wget2, the next-gen wget that’s in development works identically)

- wget extracts the example.com host name but rejects the port number due to the rubbish after the zero.

- Edge and Safari say the URL is invalid and don’t go anywhere

- Firefox and Chrome allow ‘@’ as part of the userinfo, take the ’80’ as a password and the host name then becomes ‘daniel.haxx.se’

The only somewhat modern “spec” for URLs is the WHATWG URL specification. The other major, but now somewhat aged, URL spec is RFC 3986, made by the IETF and published in 2005.

In 2015, URL problem statement and directions was published as an Internet-draft by Masinter and Ruby and it brings up most of the current URL spec problems. Some of them are also discussed in Ruby’s WHATWG URL vs IETF URI post from 2014.

What I would like to see happen…

Which group? A group!

Friends I know in the WHATWG suggest that I should dig in there and help them improve their spec. That would be a good idea if fixing the WHATWG spec would be the ultimate goal. I don’t think it is enough.

The WHATWG is highly browser focused and my interactions with members of that group that I have had in the past, have shown that there is little sympathy there for non-browsers who want to deal with URLs and there is even less sympathy or interest for URL schemes that the popular browsers don’t even support or care about. URLs cover much more than HTTP(S).

I have the feeling that WHATWG people would not like this work to be done within the IETF and vice versa. Since I’d like buy-in from both camps, and any other camps that might have an interest in URLs, this would need to be handled somehow.

It would also be great to get other major URL “consumers” on board, like authors of popular URL parsing libraries, tools and components.

Such a URL group would of course have to agree on the goal and how to get there, but I’ll still provide some additional things I want to see.

Update: I want to emphasize that I do not consider the WHATWG’s job bad, wrong or lost. I think they’ve done a great job at unifying browsers’ treatment of URLs. I don’t mean to belittle that. I just know that this group is only a small subset of the people who probably should be involved in a unified URL standard.

A single fixed spec

I can’t see any compelling reasons why a URL specification couldn’t reach a stable state and get published as *the* URL standard. The “living standard” approach may be fine for certain things (and in particular browsers that update every six weeks), but URLs are supposed to be long-lived and inter-operate far into the future so they really really should not change. Therefore, I think the IETF documentation model could work well for this.

The WHATWG spec documents what browsers do, and browsers do what is documented. At least that’s the theory I’ve been told, and it causes a spinning and never-ending loop that goes against my wish.

Document the format

The WHATWG specification is written in a pseudo code style, describing how a parser would “walk” over the string with a state machine and all. I know some people like that, I find it utterly annoying and really hard to figure out what’s allowed or not. I much more prefer the regular RFC style of describing protocol syntax.

IDNA

Can we please just say that host names in URLs should be handled according to IDNA2008 (RFC 5895)? WHATWG URL doesn’t state any IDNA spec number at all.

Move out irrelevant sections

“Irrelevant” when it comes to documenting the URL format that is. The WHATWG details several things that are related to URL for browsers but are mostly irrelevant to other URL consumers or producers. Like section “5. application/x-www-form-urlencoded” and “6. API”.

They would be better placed in a “URL considerations for browsers” companion document.

Working doesn’t imply sensible

So browsers accept URLs written with thousands of forward slashes instead of two. That is not a good reason for the spec to say that a URL may legitimately contain a thousand slashes. I’m totally convinced there’s no critical content anywhere using such formatted URLs and no soul will be sad if we’d restricted the number to a single-digit. So we should. And yeah, then browsers should reject URLs using more.

The slashes are only an example. The browsers have used a “liberal in what you accept” policy for a lot of things since forever, but we must resist to use that as a basis when nailing down a standard.

The odds of this happening soon?

I know there are individuals interested in seeing the URL situation getting worked on. We’ve seen articles and internet-drafts posted on the issue several times the last few years. Any year now I think we will see some movement for real trying to fix this. I hope I will manage to participate and contribute a little from my end.

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?