I sent out the release announcement for curl 7.52.0 exactly 07:59 in the morning of December 21, 2016. A Wednesday. We typically release curl on Wednesdays out of old habit. It is a good release day.

curl 7.52.0 was just as any other release. Perhaps with a slightly larger set of new features than what’s typical for us. We introduce TLS 1.3 support, we now provide HTTPS-proxy support and the command line tool has this option called –fail-early that I think users will start to appreciate once they start to discover it. We also announced three fixed security vulnerabilities. And some other good things.

I pushed the code to git, signed and uploaded the tarballs, I updated the info on the web site and I sent off that release announcement email and I felt good. Release-time good. That short feeling of relief and starting over on a new slate that I often experience these release days. Release days make me happy.

Any bets?

It is not unusual for someone to find a bug really fast after a release has shipped. As I was feeling good, I had to joke in the #curl IRC channel (42 minutes after that email):

08:41 <bagder> any bets on when the first bug report on the new release shows up? =)

Hours passed and maybe, just maybe there was not going to be any quick bugs filed on this release?

But of course. I wouldn’t write this blog post if it all had been nice and dandy. At 14:03, I got the email. 6 hours and 4 minutes since I wrote the 7.52.0 announcement email.

The email was addressed to the curl project security email list and included a very short patch and explanation how the existing code is wrong and needs “this fix” to work correctly. And it was entirely correct!

Now I didn’t feel that sense of happiness anymore. For some reason it was now completely gone and instead I felt something that involved sensations like rage, embarrassment and general tiredness. How the [beep] could this slip through like this?

I’ve done releases in the past that were broken to various extents but this is a sort of a new record and an unprecedented event. Enough time had passed that I couldn’t just yank the package from the download page either. I had to take it through the correct procedures.

What happened?

As part of a general code cleanup during this last development round, I changed all the internals to use a proper internal API to get random data and if libcurl is built with a TLS library it uses its provided API to get secure and safe random data. As a move to improve our use of random internally. We use this internal API for getting the nonce in authentication mechanisms such as Digest and NTLM and also for generating the boundary string in HTTP multipart formposts and more. (It is not used for any TLS or SSH level protocol stuff though.)

I did the largest part of the random overhaul of this in commit f682156a4f, just a little over a month ago.

Of course I made sure that all test cases kept working and there were no valgrind reports or anything, the code didn’t cause any compiler warnings. It did not generate any reports in the many clang-analyzer or Coverity static code analyzer runs we’ve done since. We run clang-analyzer daily and Coverity perhaps weekly.

But there’s a valgrind report just here!

Kamil Dudka, who sent the 14:03 email, got a valgrind error and that’s what set him off – but how come he got that and I didn’t?

The explanation consists of the following two conditions that together worked to hide the problem for us quite successfully:

- I (and I suppose several of the other curl hackers) usually build curl and libcurl “debug enabled”. This allows me to run more tests, do more diagnostics and debug it easier when I run into problems. It also provides a system with “fake random” so that we can actually verify that functions that otherwise use real random values generate the correct output when given a known random value… and yeah, this debug system prevented valgrind from detecting any problem!

- In the curl test suite we once had a problem with valgrind generating reports on third party libraries etc which then ended up as false positives. We then introduced a “valgrind report parser” that would detect if the report concerns curl or something else. It turns out this parser doesn’t detect the errors if curl is compiled without the cc’s -g command line option. And of course… curl and libcurl both build without -g by default!

The patch?

The vulnerable function basically uses this simple prototype. It is meant to get an “int” worth of random value stored in the buffer ‘rnd’ points to. That’s 4 bytes.

randit(struct Curl_easy *data, unsigned int *rnd)

But due to circumstances I can’t explain on anything other than my sloppy programming, I managed to write the function store random value in the actual pointer instead of the buffer it points to. So when the function returns, there’s nothing stored in the buffer. No 4 bytes of random. Just the uninitialized value of whatever happened to be there, on the stack.

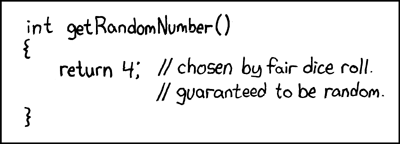

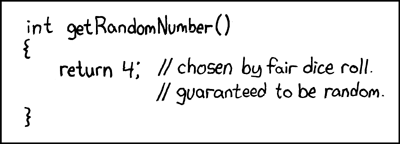

The patch that fixes this problem looks like this (with some names shortened to simplify but keep the idea):

- res = random(data, (char *)&rnd, sizeof(rnd));

+ res = random(data, (char *)rnd, sizeof(*rnd));

So yeah. I introduced this security flaw in 7.52.0. We had it fixed in 7.52.1, released roughly 48 hours later.

(I really do not need comments on what other languages that wouldn’t have allowed this mistake or otherwise would’ve brought us world peace a long time ago.)

Make it not happen again

The primary way to make this same mistake not happen again easily, is that I’m removing the valgrind report parsing function from the test suite and we will now instead assume that valgrind reports will be legitimate and if not, work on suppressing the false positives in a better way.

References

This flaw is officially known as CVE-2016-9594

The real commit that fixed this problem is here, or as stand-alone patch.

The full security advisory for this flaw is here: https://curl.haxx.se/docs/adv_20161223.html

Facepalm photo by Alex E. Proimos.

xkcd: 221

Today Mozilla revealed the new logo and “refreshed identity”. The new Mozilla logo uses the colon-slash-slash sequence already featured in curl’s logo as I’ve discussed previously here from back before the final decision (or layout) was complete.

Today Mozilla revealed the new logo and “refreshed identity”. The new Mozilla logo uses the colon-slash-slash sequence already featured in curl’s logo as I’ve discussed previously here from back before the final decision (or layout) was complete.

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?

The main effect is that normal end users find my email address via the

The main effect is that normal end users find my email address via the  shed at the end of October 2016.

shed at the end of October 2016.