“given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”

The saying (also known as Linus’ law) doesn’t say that the bugs are found fast and neither does it say who finds them. My version of the law would be much more cynical, something like: “eventually, bugs are found“, emphasizing the ‘eventually’ part.

(Jim Zemlin apparently said the other day that it can work the Linus way, if we just fund the eyeballs to watch. I don’t think that’s the way the saying originally intended.)

Because in reality, many many bugs are never really found by all those given “eyeballs” in the first place. They are found when someone trips over a problem and is annoyed enough to go searching for the culprit, the reason for the malfunction. Even if the code is open and has been around for years it doesn’t necessarily mean that any of all the people who casually read the code or single-stepped over it will actually ever discover the flaws in the logic. The last few years several world-shaking bugs turned out to have existed for decades until discovered. In code that had been read by lots of people – over and over.

So sure, in the end the bugs were found and fixed. I would argue though that it wasn’t because the projects or problems were given enough eyeballs. Some of those problems were found in extremely popular and widely used projects. They were found because eventually someone accidentally ran into a problem and started digging for the reason.

Time until discovery in the curl project

I decided to see how it looks in the curl project. A project near and dear to me. To take it up a notch, we’ll look only at security flaws. Not only because they are the probably most important bugs we’ve had but also because those are the ones we have the most carefully noted meta-data for. Like when they were reported, when they were introduced and when they were fixed.

We have no less than 30 logged vulnerabilities for curl and libcurl so far through-out our history, spread out over the past 16 years. I’ve spent some time going through them to see if there’s a pattern or something that sticks out that we should put some extra attention to in order to improve our processes and code. While doing this I gathered some random info about what we’ve found so far.

On average, each security problem had been present in the code for 2100 days when fixed – that’s more than five and a half years. On average! That means they survived about 30 releases each. If bugs truly are shallow, it is still certainly not a fast processes.

Perhaps you think these 30 bugs are really tricky, deeply hidden and complicated logic monsters that would explain the time they took to get found? Nope, I would say that every single one of them are pretty obvious once you spot them and none of them take a very long time for a reviewer to understand.

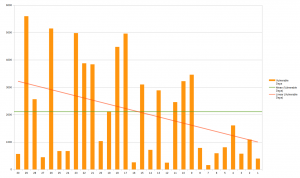

This first graph (click it for the large version) shows the period each problem remained in the code for the 30 different problems, in number of days. The leftmost bar is the most recent flaw and the bar on the right the oldest vulnerability. The red line shows the trend and the green is the average.

The trend is clearly that the bugs are around longer before they are found, but since the project is also growing older all the time it sort of comes naturally and isn’t necessarily a sign of us getting worse at finding them. The average age of flaws is aging slower than the project itself.

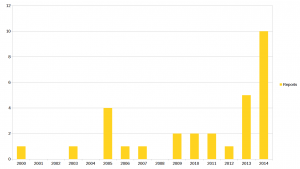

Reports per year

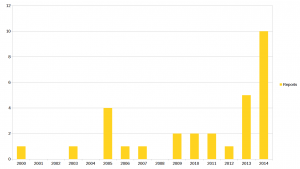

How have the reports been distributed over the years? We have a fairly linear increase in number of lines of code but yet the reports were submitted like this (now it goes from oldest to the left and most recent on the right – click for the large version):

Compare that to this chart below over lines of code added in the project (chart from openhub and shows blanks in green, comments in grey and code in blue, click it for the large version):

We received twice as many security reports in 2014 as in 2013 and we got half of all our reports during the last two years. Clearly we have gotten more eyes on the code or perhaps users pay more attention to problems or are generally more likely to see the security angle of problems? It is hard to say but clearly the frequency of security reports has increased a lot lately. (Note that I here count the report year, not the year we announced the particular problems, as they sometimes were done on the following year if the report happened late in the year.)

On average, we publish information about a found flaw 19 days after it was reported to us. We seem to have became slightly worse at this over time, the last two years the average has been 25 days.

Did people find the problems by reading code?

In general, no. Sure people read code but the typical pattern seems to be that people run into some sort of problem first, then dive in to investigate the root of it and then eventually they spot or learn about the security problem.

(This conclusion is based on my understanding from how people have reported the problems, I have not explicitly asked them about these details.)

Common patterns among the problems?

I went over the bugs and marked them with a bunch of descriptive keywords for each flaw, and then I wrote up a script to see how the frequent the keywords are used. This turned out to describe the flaws more than how they ended up in the code. Out of the 30 flaws, the 10 most used keywords ended up like this, showing number of flaws and the keyword:

9 TLS

9 HTTP

8 cert-check

8 buffer-overflow

6 info-leak

3 URL-parsing

3 openssl

3 NTLM

3 http-headers

3 cookie

I don’t think it is surprising that TLS, HTTP or certificate checking are common areas of security problems. TLS and certs are complicated, HTTP is huge and not easy to get right. curl is mostly C so buffer overflows is a mistake that sneaks in, and I don’t think 27% of the problems tells us that this is a problem we need to handle better. Also, only 2 of the last 15 flaws (13%) were buffer overflows.

The discussion following this blog post is on hacker news.

This is not my area of expertise. I had to consult

This is not my area of expertise. I had to consult