One of the persistent myths about HTTP is that it is “a simple protocol”.

Expect: – not always expected

One of the dusty spec corners of HTTP/1.1 (Section 5.1.1 of RFC 7231) explains how the Expect: header works. This is still today in 2020 one of the HTTP request headers that is very commonly ignored by servers and intermediaries.

Background

HTTP/1.1 is designed for being sent over TCP (and possibly also TLS) in a serial manner. Setting up a new connection is costly, both in terms of CPU but especially in time – requiring a number of round-trips. (I’ll detail further down how HTTP/2 fixes all these issues in a much better way.)

HTTP/1.1 provides a number of ways to allow it to perform all its duties without having to shut down the connection. One such an example is the ability to tell a client early on that it needs to provide authentication credentials before the clients sends of a large payload. In order to maintain the TCP connection, a client can’t stop sending a HTTP payload prematurely! When the request body has started to get transmitted, the only way to stop it before the end of data is to cut off the connection and create a new one – wasting time and CPU…

“We want a 100 to continue”

A client can include a header in its outgoing request to ask the server to first acknowledge that everything is fine and that it can continue to send the “payload” – or it can return status codes that informs the client that there are other things it needs to fulfill in order to have the request succeed. Most such cases typically that involves authentication.

This “first tell me it’s OK to send it before I send it” request header looks like this:

Expect: 100-continue

Servers

Since this mandatory header is widely not understood or simply ignored by HTTP/1.1 servers, clients that issue this header will have a rather short timeout and if no response has been received within that period it will proceed and send the data even without a 100.

The timeout thing is happening so often that removing the Expect: header from curl requests is a very common answer to question on how to improve POST or PUT requests with curl, when it works against such non-compliant servers.

Popular browsers

Browsers are widely popular HTTP clients but none of the popular ones ever use this. In fact, very few clients do. This is of course a chicken and egg problem because servers don’t support it very well because clients don’t and client’s don’t because servers don’t support it very well…

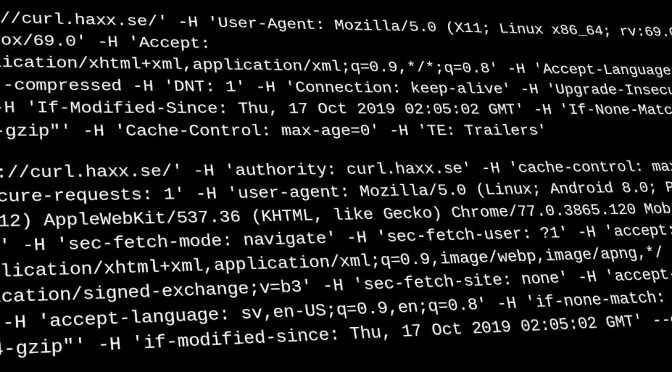

curl sends Expect:

When we implemented support for HTTP/1.1 in curl back in 2001, we wanted it done proper. We made it have a short, 1000 milliseconds, timeout waiting for the 100 response. We also made curl automatically include the Expect: header in outgoing requests if we know that the body is larger than NNN or we don’t know the size at all before-hand (and obviously, we don’t do it if we send the request chunked-encoded).

The logic being there that if the data amount is smaller than NNN, then the waste is not very big and we can just as well send it (even if we risk sending it twice) as waiting for a response etc is just going to be more time consuming.

That NNN margin value (known in the curl sources as the EXPECT_100_THRESHOLD) in curl was set to 1024 bytes already then back in the early 2000s.

Bumping EXPECT_100_THRESHOLD

Starting in curl 7.69.0 (due to ship on March 4, 2020) we catch up a little with the world around us and now libcurl will only automatically set the Expect: header if the amount of data to send in the body is larger than 1 megabyte. Yes, we raise the limit by 1024 times.

The reasoning is of course that for most Internet users these days, data sizes below a certain size isn’t even noticeable when transferred and so we adapt. We then also reduce the amount of problems for the very small data amounts where waiting for the 100 continue response is a waste of time anyway.

Credits: landed in this commit. (sorry but my WordPress stupidly can’t show the proper Asian name of the author!)

417 Expectation Failed

One of the ways that a HTTP/1.1 server can deal with an Expect: 100-continue header in a request, is to respond with a 417 code, which should tell the client to retry the same request again, only without the Expect: header.

While this response is fairly uncommon among servers, curl users who ran into 417 responses have previously had to resort to removing the Expect: header “manually” from the request for such requests. This was of course often far from intuitive or easy to figure out for users. A source for grief and agony.

Until this commit, also targeted for inclusion in curl 7.69.0 (March 4, 2020). Starting now, curl will automatically act on 417 response if it arrives as a consequence of using Expect: and then retry the request again without using the header!

Credits: I wrote the patch.

HTTP/2 avoids this all together

With HTTP/2 (and HTTP/3) this entire thing is a non-issue because with these modern protocol versions we can abort a request (stop a stream) prematurely without having to sacrifice the connection. There’s therefore no need for this crazy dance anymore!