Thursday, September 22nd 2016. An email popped up in my inbox.

Subject: ares_create_query OOB write

As one of the maintainers of the c-ares project I’m receiving mails for suspected security problems in c-ares and this was such a one. In this case, the email with said subject came from an individual who had reported a ChromeOS exploit to Google.

It turned out that this particular c-ares flaw was one important step in a sequence of necessary procedures that when followed could let the user execute code on ChromeOS from JavaScript – as the root user. I suspect that is pretty much the worst possible exploit of ChromeOS that can be done. I presume the reporter will get a fair amount of bug bounty reward for this. (Update: he got 100,000 USD for it.)

The setup and explanation on how this was accomplished is very complicated and I am deeply impressed by how this was figured out, tracked down and eventually exploited in a repeatable fashion. But bear with me. Here comes a very simplified explanation on how a single byte buffer overwrite with a fixed value could end up aiding running exploit code as root.

The main Google bug for this problem is still not open since they still have pending mitigations to perform, but since the c-ares issue has been fixed I’ve been told that it is fine to talk about this publicly.

c-ares writes a 1 outside its buffer

c-ares has a function called ares_create_query. It was added in 1.10 (released in May 2013) as an updated version of the older function ares_mkquery. This detail is mostly interesting because Google uses an older version than 1.10 of c-ares so in their case the flaw is in the old function. This is the two functions that contain the problem we’re discussing today. It used to be in the ares_mkquery function but was moved over to ares_create_query a few years ago (and the new function got an additional argument). The code was mostly unchanged in the move so the bug was just carried over. This bug was actually already present in the original ares project that I forked and created c-ares from, back in October 2003. It just took this long for someone to figure it out and report it!

I won’t bore you with exactly what these functions do, but we can stick to the simple fact that they take a name string as input, allocate a memory area for the outgoing packet with DNS protocol data and return that newly allocated memory area and its length.

Due to a logic mistake in the function, you could trick the function to allocate a too short buffer by passing in a string with an escaped trailing dot. An input string like “one.two.three\.” would then cause the allocated memory area to be one byte too small and the last byte would be written outside of the allocated memory area. A buffer overflow if you want. The single byte written outside of the memory area is most commonly a 1 due to how the DNS protocol data is laid out in that packet.

This flaw was given the name CVE-2016-5180 and was fixed and announced to the world in the end of September 2016 when c-ares 1.12.0 shipped. The actual commit that fixed it is here.

What to do with a 1?

Ok, so a function can be made to write a single byte to the value of 1 outside of its allocated buffer. How do you turn that into your advantage?

The Redhat security team deemed this problem to be of “Moderate security impact” so they clearly do not think you can do a lot of harm with it. But behold, with the right amount of imagination and luck you certainly can!

Back to ChromeOS we go.

First, we need to know that ChromeOS runs an internal HTTP proxy which is very liberal in what it accepts – this is the software that uses c-ares. This proxy is a key component that the attacker needed to tickle really badly. So by figuring out how you can send the correctly crafted request to the proxy, it would send the right string to c-ares and write a 1 outside its heap buffer.

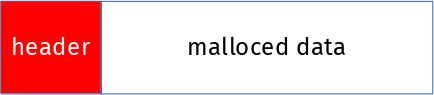

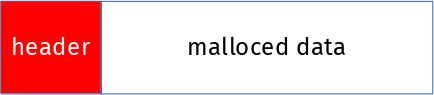

ChromeOS uses dlmalloc for managing the heap memory. Each time the program allocates memory, it will get a pointer back to the request memory region, and dlmalloc will put a small header of its own just before that memory region for its own purpose. If you ask for N bytes with malloc, dlmalloc will use ( header size + N ) and return the pointer to the N bytes the application asked for. Like this:

With a series of cleverly crafted HTTP requests of various sizes to the proxy, the attacker managed to create a hole of freed memory where he then reliably makes the c-ares allocated memory to end up. He knows exactly how the ChromeOS dlmalloc system works and its best-fit allocator, how big the c-ares malloc will be and thus where the overwritten 1 will end up. When the byte 1 is written after the memory, it is written into the header of the next memory chunk handled by dlmalloc:

The specific byte of that following dlmalloc header that it writes to, is used for flags and the lowest bits of size of that allocated chunk of memory.

Writing 1 to that byte clears 2 flags, sets one flag and clears the lowest bits of the chunk size. The important flag it sets is called prev_inuse and is used by dlmalloc to tell if it can merge adjacent areas on free. (so, if the value 1 simply had been a 2 instead, this flaw could not have been exploited this way!)

When the c-ares buffer that had overflowed is then freed again, dlmalloc gets fooled into consolidating that buffer with the subsequent one in memory (since it had toggled that bit) and thus the larger piece of assumed-to-be-free memory is partly still being in use. Open for manipulations!

Using that memory buffer mess

This freed memory area whose end part is actually still being used opened up the play-field for more “fun”. With doing another creative HTTP request, that memory block would be allocated and used to store new data into.

The attacker managed to insert the right data in that further end of the data block, the one that was still used by another part of the program, mostly since the proxy pretty much allowed anything to get crammed into the request. The attacker managed to put his own code to execute in there and after a few more steps he ran whatever he wanted as root. Well, the user would have to get tricked into running a particular JavaScript but still…

I cannot even imagine how long time it must have taken to make this exploit and how much work and sweat that were spent. The report I read on this was 37 very detailed pages. And it was one of the best things I’ve read in a long while! When this goes public in the future, I hope at least parts of that description will become available for you as well.

A lesson to take away from this?

No matter how limited or harmless a flaw may appear at a first glance, it can serve a malicious purpose and serve as one little step in a long chain of events to attack a system. And there are skilled people out there, ready to figure out all the necessary steps.

Update: A detailed write-up about this flaw (pretty much the report I refer to above) by the researcher who found it was posted on Google’s Project Zero blog on December 14:

Chrome OS exploit: one byte overflow and symlinks.

I’ve been a gmail user for many years (maybe ten). Especially since the introduction of smart phones it has been a really convenient system to read email on the go. I rarely respond to email from my phone but I’ve done that occasionally too and it has worked adequately.

I’ve been a gmail user for many years (maybe ten). Especially since the introduction of smart phones it has been a really convenient system to read email on the go. I rarely respond to email from my phone but I’ve done that occasionally too and it has worked adequately. spam filter. I do run spamassassin on my server and it catches the large bulk of all spams, but having the gmail spam system on top of that was able to block more silliness from my phone than spamassassin does alone.

spam filter. I do run spamassassin on my server and it catches the large bulk of all spams, but having the gmail spam system on top of that was able to block more silliness from my phone than spamassassin does alone.

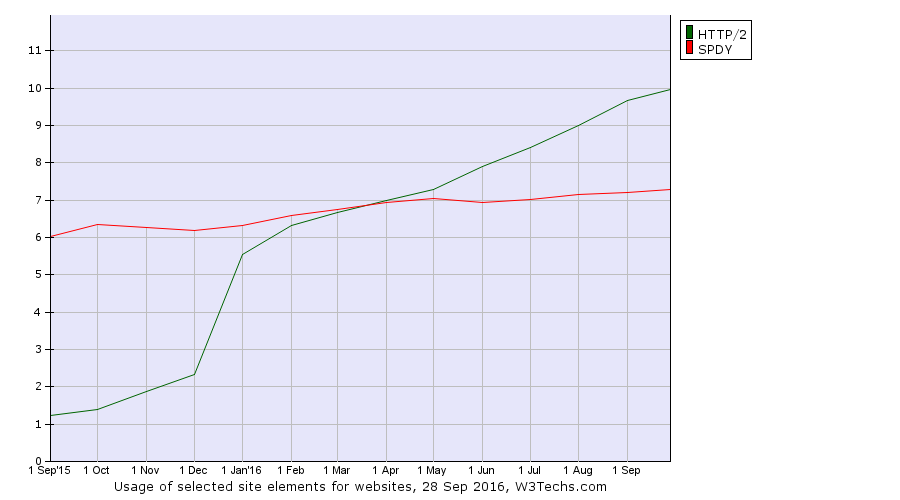

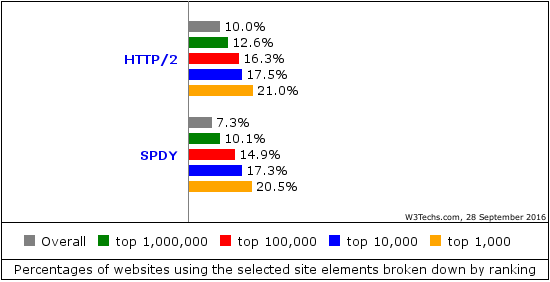

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?

Still, there are scenarios where HTTP/1’s multiple connections win over HTTP/2 in performance tests. Why is that and what is being done about it? Wasn’t HTTP/2 supposed to be the silver bullet?

shed at the end of October 2016.

shed at the end of October 2016. Back in 2013, it came to light that

Back in 2013, it came to light that