Already at the time when we shipped the previous release, 7.61.0, I had decided I wanted to do a patch release next. We had some pretty serious HTTP/2 bugs in the pipe to get fixed and there were a bunch of other unresolved issues also awaiting their treatments. Then I took off on vacation and and the HTTP/2 fixes took a longer time than expected to get on top of, so I subsequently decided that this would become a bug-fix-only release cycle. No features and no changes would be merged into master. So this is what eight weeks of only bug-fixes can look like.

Numbers

the 176th release

0 changes

56 days (total: 7,419)

102 bug fixes (total: 4,640)

151 commits (total: 23,439)

0 new curl_easy_setopt() options (total: 258)

0 new curl command line option (total: 218)

46 contributors, 21 new (total: 1,787)

27 authors, 14 new (total: 612)

1 security fix (total: 81)

Notable bug-fixes this cycle

Among the many small fixes that went in, I feel the following ones deserve a little extra highlighting…

NTLM password overflow via integer overflow

This latest security fix (CVE-2018-14618) is almost identical to an earlier one we fixed back in 2017 called CVE-2017-8816, and is just as silly…

The internal function Curl_ntlm_core_mk_nt_hash() takes a password argument, the same password that is passed to libcurl from an application. It then gets the length of that password and allocates a memory area that is twice the length, since it needs to expand the password. Due to a lack of checks, this calculation will overflow and wrap on a 32 bit machine if a password that is longer than 2 gigabytes is passed to this function. It will then lead to a very small memory allocation, followed by an attempt to write a very long password to that small memory buffer. A heap memory overflow.

Some mitigating details: most architectures support 64 bit size_t these days. Most applications won’t allow passing in passwords that are two gigabytes.

This bug has been around since libcurl 7.15.4, released back in 2006!

Oh, and on the curl web site we now use the CVE number in the actual URL for all the security vulnerabilities to make them easier to find and refer to.

HTTP/2 issues

This was actually a whole set of small problems that together made the new crawler example not work very well – until fixed. I think it is safe to say that HTTP/2 users of libcurl have previously used it in a pretty “tidy” fashion, because I believe I corrected four or five separate issues that made it misbehave. It was rather pure luck that has made it still work as well as it has for past users!

This was actually a whole set of small problems that together made the new crawler example not work very well – until fixed. I think it is safe to say that HTTP/2 users of libcurl have previously used it in a pretty “tidy” fashion, because I believe I corrected four or five separate issues that made it misbehave. It was rather pure luck that has made it still work as well as it has for past users!

Another HTTP/2 bug we ran into recently involved us discovering a little quirk in the underlying nghttp2 library, which in some very special circumstances would refuse to blank out the stream id to struct pointer mapping which would lead to it delivering a pointer to a stale (already freed) struct at a later point. This is fixed in nghttp2 now, shipped in its recent 1.33.0 release.

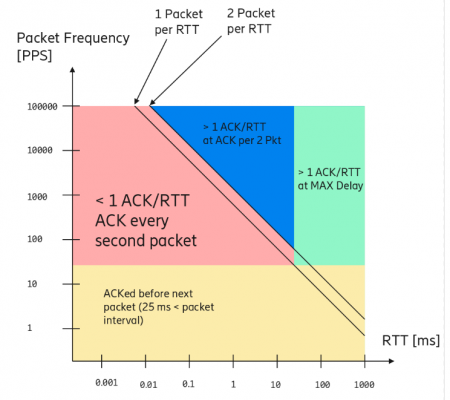

Windows send-buffer tuning

Making uploads on Windows from between two to seven times faster than before is certainly almost like a dream come true. This is what 7.61.1 offers!

Upload buffer size increased

In tests triggered by the fix above, it was noticed that curl did not meet our performance expectations when doing uploads on really high speed networks, notably on localhost or when using SFTP. We could easily double the speed by just increasing the upload buffer size. Starting now, curl allocates the upload buffer on demand (since many transfers don’t need it), and now allocates a 64KB buffer instead of the previous 16KB. It has been using 16KB since the 2001, and with the on-demand setup and the fact that computer memories have grown a bit during 17 years I think it is well motivated.

A future curl version will surely allow the application to set this upload buffer size. The receive buffer size can already be set.

Darwinssl goes ALPN

While perhaps in the grey area of what a bugfix can be, this fix allows curl to negotiate ALPN using the darwinssl backend, which by extension means that curl built to use darwinssl can now – finally – do HTTP/2 over HTTPS! Darwinssl is also known under the name Secure Transport, the native TLS library on macOS.

Note however that macOS’ own curl builds that Apple ships are no longer built to use Secure Transport, they use libressl these days.

The Auth Bearer fix

When we added support for Auth Bearer tokens in 7.61.0, we accidentally caused a regression that now is history. This bug seems to in particular have hit git users for some reason.

-OJ regression

The introduction of bold headers in 7.61.0 caused a regression which made a command line like “curl -O -J http://example.com/” to fail, even if a Content-Disposition: header with a correct file name was passed on.

Cookie order

Old readers of this blog may remember my ramblings on cookie sort order from back in the days when we worked on what eventually became RFC 6265.

Old readers of this blog may remember my ramblings on cookie sort order from back in the days when we worked on what eventually became RFC 6265.

Anyway, we never did take all aspects of that spec into account when we sort cookies on the HTTP headers sent off to servers, and it has very rarely caused users any grief. Still, now Daniel Gustafsson did a glorious job and tweaked the code to also take creation order into account, exactly like the spec says we should! There’s still some gotchas in this, but at least it should be much closer to what the spec says and what some sites might assume a cookie-using client should do…

Unbold properly

Yet another regression. Remember how curl 7.61.0 introduced the cool bold headers in the terminal? Turns out I of course had my escape sequences done wrong, so in a large number of terminal programs the end-of-bold sequence (“CSI 21 m”) that curl sent didn’t actually switch off the bold style. This would lead to the terminal either getting all bold all the time or on some terminals getting funny colors etc.

Yet another regression. Remember how curl 7.61.0 introduced the cool bold headers in the terminal? Turns out I of course had my escape sequences done wrong, so in a large number of terminal programs the end-of-bold sequence (“CSI 21 m”) that curl sent didn’t actually switch off the bold style. This would lead to the terminal either getting all bold all the time or on some terminals getting funny colors etc.

In 7.61.1, curl sends the “switch off all styles” code (“CSI 0 m”) that hopefully should work better for people!

Next release!

We’ve held up a whole bunch of pull requests to ship this patch-only release. Once this is out the door, we’ll open the flood gates and accept the nearly 10 changes that are eagerly waiting merge. Expect my next release blog post to mention several new things in curl!

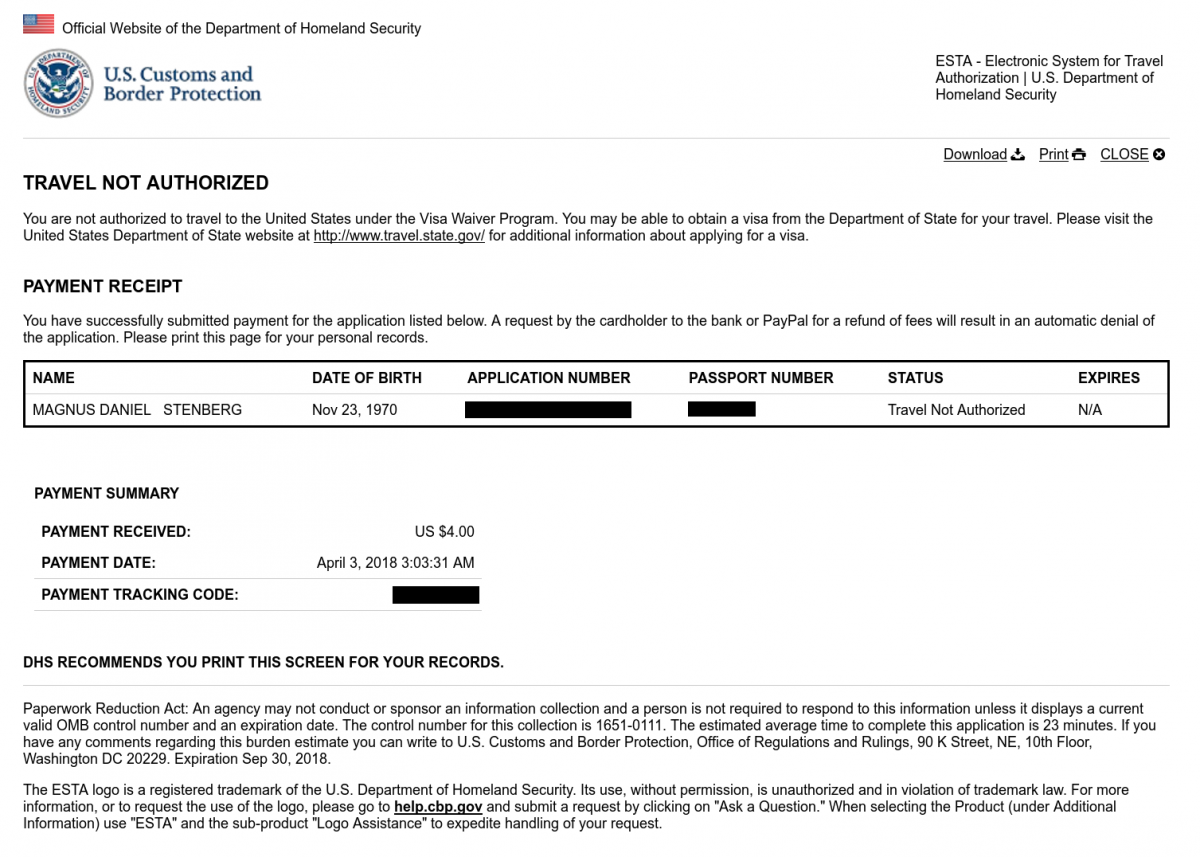

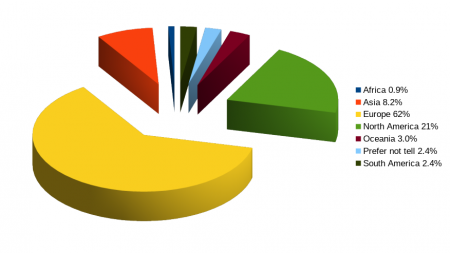

Over time, we’ve slowly been adjusting the

Over time, we’ve slowly been adjusting the

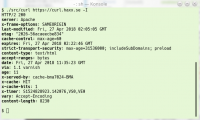

When I answered the interviewer’s question that I work for Mozilla, he responded “Aha, Firefox?” – which brightened up my moment a little.

When I answered the interviewer’s question that I work for Mozilla, he responded “Aha, Firefox?” – which brightened up my moment a little.

The

The