Short recap: I work on network code for Mozilla. Bug 939318 is one of “mine” – yesterday I landed a fix (a patch series with 6 individual patches) for this and I wanted to explain what goodness that should (might?) come from this!

diffstat

diffstat reports this on the complete patch series:

29 files changed, 920 insertions(+), 162 deletions(-)

The change set can be seen in mozilla-central here. But I guess a proper description is easier for most…

The bouncy road to inclusion

This feature set and associated problems with it has been one of the most time consuming things I’ve developed in recent years, I mean in relation to the amount of actual code produced. I’ve had it “landed” in the mozilla-inbound tree five times and yanked out again before it landed correctly (within a few hours), every time of course reverted again because I had bugs remaining in there. The bugs in this have been really tricky with a whole bunch of timing-dependent and race-like problems and me being unfamiliar with a large part of the code base that I’m working on. It has been a highly frustrating journey during periods but I’d like to think that I’ve learned a lot about Firefox internals partly thanks to this resistance.

As I write this, it has not even been 24 hours since it got into m-c so there’s of course still a risk there’s an ugly bug or two left, but then I also hope to fix the pending problems without having to revert and re-apply the whole series…

Many ways to connect to networks

In many network setups today, you get an environment and a network “experience” that is crafted for that particular place. For example you may connect to your work over a VPN where you get your company DNS and you can access sites and services you can’t even see when you connect from the wifi in your favorite coffee shop. The same thing goes for when you connect to that captive portal over wifi until you realize you used the wrong SSID and you switch over to the access point you were supposed to use.

In many network setups today, you get an environment and a network “experience” that is crafted for that particular place. For example you may connect to your work over a VPN where you get your company DNS and you can access sites and services you can’t even see when you connect from the wifi in your favorite coffee shop. The same thing goes for when you connect to that captive portal over wifi until you realize you used the wrong SSID and you switch over to the access point you were supposed to use.

For every one of these setups, you get different DHCP setups passed down and you get a new DNS server and so on.

These days laptop lids are getting closed (and the machine is put to sleep) at one place to be opened at a completely different location and rarely is the machine rebooted or the browser shut down.

Switching between networks

Switching from one of the networks to the next is of course something your operating system handles gracefully. You can even easily be connected to multiple ones simultaneously like if you have both an Ethernet card and wifi.

Enter browsers. Or in this case let’s be specific and talk about Firefox since this is what I work with and on. Firefox – like other browsers – will cache images, it will cache DNS responses, it maintains connections to sites a while even after use, it connects to some sites even before you “go there” and so on. All in the name of giving the users an as good and as fast experience as possible.

The combination of keeping things cached and alive, together with the fact that switching networks brings new perspectives and new “truths” offers challenges.

Realizing the situation is new

The changes are not at all mind-bending but are basically these three parts:

- Make sure that we detect network changes, even if just the set of available interfaces change. Send an event for this.

- Make sure the necessary parts of the code listens and understands this “network topology changed” event and acts on it accordingly

- Consider coming back from “sleep” to be a network changed event since we just cannot be sure of the network situation anymore.

The initial work has been made for Windows only but it allows us to smoothen out any rough edges before we continue and make more platforms support this.

The network changed event can be disabled by switching off the new “network.notify.changed” preference. If you do end up feeling a need for that, I really hope you file a bug explaining the details so that we can work on fixing it!

Act accordingly

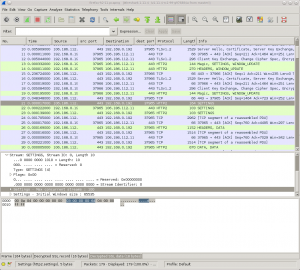

So what is acting properly? What if the network changes in a way so that your active connections suddenly can’t be used anymore due to the new rules and routing and what not? We attack this problem like this: once we get a “network changed” event, we “allow” connections to prove that they are still alive and if not they’re torn down and re-setup when the user tries to reload or whatever. For plain old HTTP(S) this means just seeing if traffic arrives or can be sent off within N seconds, and for websockets, SPDY and HTTP2 connections it involves sending an actual ping frame and checking for a response.

The internal DNS cache was a bit tricky to handle. I initially just flushed all entries but that turned out nasty as I then also killed ongoing name resolves that caused errors to get returned. Now I instead added logic that flushes all the already resolved names and it makes names “in transit” to get resolved again so that they are done on the (potentially) new network that then can return different addresses for the same host name(s).

This should drastically reduce the situation that could happen before when Firefox would basically just freeze and not want to do any requests until you closed and restarted it. (Or waited long enough for other timeouts to trigger.)

The ‘N seconds’ waiting period above is actually 5 seconds by default and there’s a new preference called “network.http.network-changed.timeout” that can be altered at will to allow some experimentation regarding what the perfect interval truly is for you.

Initially on Windows only

Initially on Windows only

My initial work has been limited to getting the changed event code done for the Windows back-end only (since the code that figures out if there’s news on the network setup is highly system specific), and now when this step has been taken the plan is to introduce the same back-end logic to the other platforms. The code that acts on the event is pretty much generic and is mostly in place already so it is now a matter of making sure the event can be generated everywhere.

My plan is to start on Firefox OS and then see if I can assist with the same thing in Firefox on Android. Then finally Linux and Mac.

I started on Windows since Windows is one of the platforms with the largest amount of Firefox users and thus one of the most prioritized ones.

More to do

There’s separate work going on for properly detecting captive portals. You know the annoying things hotels and airports for example tend to have to force you to do some login dance first before you are allowed to use the internet at that location. When such a captive portal is opened up, that should probably qualify as a network change – but it isn’t yet.

Initially on Windows only

Initially on Windows only