This is a feature-packed release with more new stuff than usual.

Numbers

the 177th release

10 changes

56 days (total: 7,419)

118 bug fixes (total: 4,758)

238 commits (total: 23,677)

5 new public libcurl functions (total: 80)

2 new curl_easy_setopt() options (total: 261)

1 new curl command line option (total: 219)

49 contributors, 21 new (total: 1,808)

38 authors, 19 new (total: 632)

3 security fixes (total: 84)

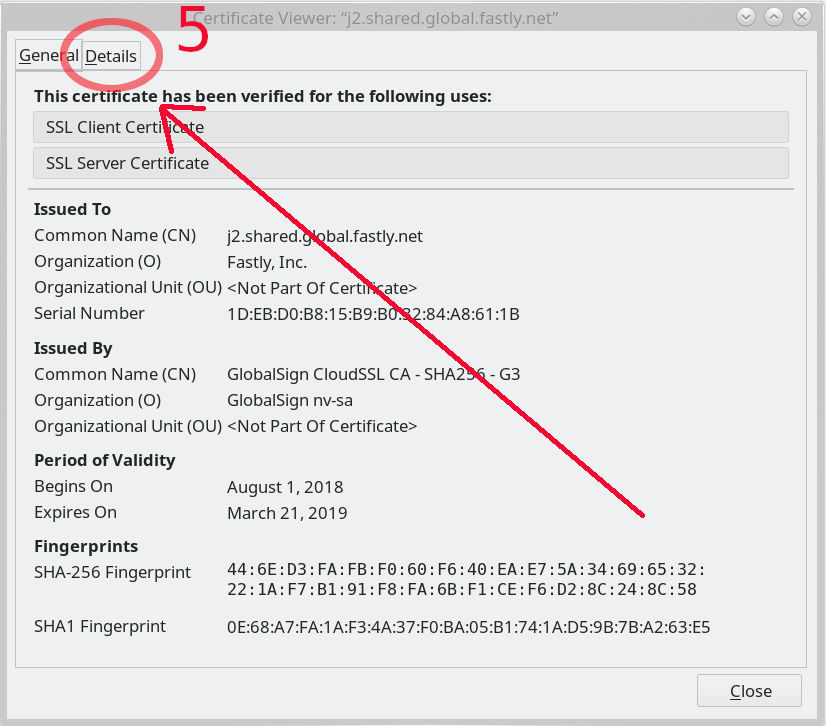

Security

New since the previous release is the dedicated curl bug bounty program. I’m not sure if this program has caused any increase in reports as it feels like a little too early to tell.

CVE-2018-16839 – an integer overflow case that triggers on 32 bit machines given extremely long input user name argument, when using POP3, SMTP or IMAP.

CVE-2018-16840 – a use-after-free issue. Immediately after having freed a struct in the easy handle close function, libcurl might write a boolean to that struct!

CVE-2018-16842 – is a vulnerability in the curl command line tool’s “warning” message display code which can make it read outside of a buffer and send unintended memory contents to stderr.

All three of these issues are deemed to have low severity and to be hard to exploit.

New APIs!

We introduce a brand new URL API, that lets applications parse and generate URLs, using libcurl’s own parser. Five new public functions in one go there! The link goes to the separate blog entry that explained it.

A brand new function is introduced (curl_easy_upkeep) to let applications maintain idle connections while no transfers are in progress! Perfect to maintain HTTP/2 connections for example that have a PING frame that might need attention.

More changes

Applications using libcurl’s multi interface will now get multiplexing enabled by default, and HTTP/2 will be selected for HTTPS connections. With these new changes of the default behavior, we hope that lots of applications out there just transparently and magically will start to perform better over time without anyone having to change anything!

We shipped DNS-over-HTTPS support. With DoH, your internet client can do secure and private name resolves easier. Follow the link for the full blog entry with details.

The good people at MesaLink has a TLS library written in rust, and in this release you can build libcurl to use that library. We haven’t had a new TLS backend supported since 2012!

Our default IMAP handling is slightly changed, to use the proper standards compliant “UID FETCH” method instead of just “FETCH”. This might introduce some changes in behavior so if you’re doing IMAP transfers, I advice you to mind your step into this upgrade.

Starting in 7.62.0, applications can now set the buffer size libcurl will use for uploads. The buffers used for download and upload are separate and applications have been able to specify the download buffer size for a long time already and now they can finally do it for uploads too. Most applications won’t need to bother about it, but for some edge case uses there are performance gains to be had by bumping this size up. For example when doing SFTP uploads over high latency high bandwidth connections.

curl builds that use libressl will now at last show the correct libressl version number in the “curl -V” output.

Deprecating legacy

CURLOPT_DNS_USE_GLOBAL_CACHE is deprecated! If there’s not a massive complaint uproar, this means this option will effectively be made pointless in April 2019. The global cache isn’t thread-safe and has been called obsolete in the docs since 2002!

HTTP pipelining support is deprecated! Starting in this version, asking for pipelining will be ignored by libcurl. We strongly urge users to switch to and use HTTP/2, which in 99% of the cases is the better alternative to HTTP/1.1 Pipelining. The pipelining code in libcurl has stability problems. The impact of disabled pipelining should be minimal but some applications will of course notice. Also note the section about HTTP/2 and multiplexing by default under “changes” above.

To get an overview of all things marked for deprecation in curl and their individual status check out this page.

Interesting bug-fixes

TLS 1.3 support for GnuTLS landed. Now you can build curl to support TLS 1.3 with most of the TLS libraries curl supports: GnuTLS, OpenSSL, BoringSSL, libressl, Secure Transport, WolfSSL, NSS and MesaLink.

curl got Windows VT Support and UTF-8 output enabled, which should make fancy things like “curl wttr.in” to render nice outputs out of the box on Windows as well!

The TLS backends got a little cleanup and error code use unification so that they should now all return the same error code for the same problem no matter which backend you use!

When you use curl to do URL “globbing” as for example “curl http://localhost/[1-22]” to fetch a range or a series of resources and accidentally mess up the range, curl would previously just say that it detected an error in the glob pattern. Starting now, it will also try to show exactly where in which pattern it found the error that made it stop processing it.

CI

The curl for Windows CI builds on AppVeyor are now finally also running the test suite! Actually making sure that the Windows build is intact in every commit and PR is a huge step forward for us and our aim to keep curl functional. We also build several additional and different build combinations on Windows in the CI than we did previously. All in an effort to reduce regressions.

We’ve added four new checks to travis (that run on every pull-request and commit):

- The “tidy” build runs clang-tidy on all sources in src/ and lib/.

- a –disable-verbose build makes sure this configure option still builds curl warning-free

- the “distcheck” build now scans all files for accidental unicode BOM markers

- a MesaLink-using build verifies this configuration

CI build times

We’re right now doing 40 builds on every commit, spending around 12 hours of CPU time for a full round. With >230 landed commits in the tree that originated from 150-something pull requests, with a lot of them having been worked out using multiple commits, we’ve done perhaps 500 full round CI builds in these 56 days.

This of course doesn’t include all the CPU time developers spend locally before submitting PRs or even the autobuild system that currently runs somewhere in the order of 50 builds per day. If we assume an average time spent for each build+test to take 20 minutes, this adds another 930 hours of CI hours done from the time of the previous release until this release.

To sum up, that’s about 7,000 hours of CI spent in 56 days, equaling about 520% non-stop CPU time!

We are grateful for all the help we get!

Next release

The next release will ship on December 12, 2018 unless something urgent happens before that.

Note that this date breaks the regular eight week release cycle and is only six weeks off. We do this since the originally planned date would happen in the middle of Christmas when “someone” plans to be off traveling…

The next release will probably become 7.63.0 since we already have new changes knocking on the door waiting to get merged that will warrant another minor number bump. Stay tuned for details!

It’s been

It’s been  I had already before I joined the Firefox development understood some of the challenges of making a browser in the modern era, but that understanding has now been properly enriched with lots of hands-on and code-digging in sometimes decades-old messy C++, a spaghetti armada of threads and the wild wild west of users on the Internet.

I had already before I joined the Firefox development understood some of the challenges of making a browser in the modern era, but that understanding has now been properly enriched with lots of hands-on and code-digging in sometimes decades-old messy C++, a spaghetti armada of threads and the wild wild west of users on the Internet. I had worked on curl for a very long time already before joining Mozilla and I expect to keep doing curl and other open source things even going forward. I don’t think my choice of future employer should have to affect that negatively too much, except of course in periods.

I had worked on curl for a very long time already before joining Mozilla and I expect to keep doing curl and other open source things even going forward. I don’t think my choice of future employer should have to affect that negatively too much, except of course in periods. I was involved in the IETF HTTPbis working group for many years before I joined Mozilla (for over ten years now!) and I hope to be involved for many years still. I still have a lot of things I want to do with curl and to keep curl the champion of its class I need to stay on top of the game.

I was involved in the IETF HTTPbis working group for many years before I joined Mozilla (for over ten years now!) and I hope to be involved for many years still. I still have a lot of things I want to do with curl and to keep curl the champion of its class I need to stay on top of the game.