That’s the thought that ran through my head when I read the email I had just received.

GAAAAAAAAAAAAH

You know the feeling when the realization hits you that you did something really stupid? And you did it hours ago and people already noticed so its too late to pretend it didn’t happen or try to cover it up and whistle innocently. Nope, none of those options were available anymore. The truth was out there.

I had messed up royally.

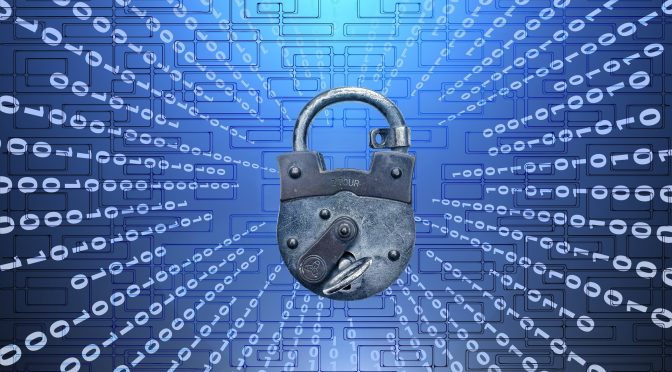

What triggered this sudden journey of emotions and sharp sense of pain in my soul, was an email I received at 10:18, Friday March 9 2018. The encrypted email pointed out to me in clear terms that there was information available publicly on the curl web site about the security vulnerabilities that we intended to announce in association with the next curl release, on March 21. (The person who emailed me is a member of a group that was informed by me about these issues ahead of time.)

In the curl project, we never reveal nor show any information about known security flaws until we ship fixes for them and publish their corresponding security advisories that explain the flaws, the risks, the fixes and work-arounds in detail. This of course in the name of keeping users safe. We don’t want bad guys to learn about problems and flaws until we also offer fixes for them. That is, unless you screw up like me.

It took me a few minutes until I paused my work I was doing at the moment and actually read the email, but once I did I acted immediately and at 10:24 I had reverted the change on the web site and purged the URL from the CDN so the information was no longer publicly visible there.

The entire curl web site is however kept in a public git repository, so while the sensitive information was no longer immediately notable on the site, it was still out of the bag and there was just no taking it back. Not to mention that we don’t know how many people that already updated their git clones etc.

I pushed the particular file containing the “extra information” to the web site’s git repository at 01:26 CET the same early morning and since the web site updates itself in a cronjob every 20 minutes we know the information became available just after 01:40. At which time I had already gone to bed.

The sensitive information was displayed on the site for 8 hours and 44 minutes. The security page table showed these lines at the top:

| # | Vulnerability | Date | First | Last | CVE | CWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | RTSP RTP buffer over-read | February 20, 2018 | 7.20.0 | 7.58.0 | CVE-2018-1000122 | CWE-126: Buffer Over-read |

| 77 | LDAP NULL pointer dereference | March 06, 2018 | 7.21.0 | 7.58.0 | CVE-2018-1000121 | CWE-476: NULL Pointer Dereference |

| 76 | FTP path trickery leads to NIL byte out of bounds write | March 21, 2018 | 7.12.3 | 7.58.0 | CVE-2018-1000120 | CWE-122: Heap-based Buffer Overflow |

I only revealed the names of the flaws and their corresponding CWE (Common Weakness Enumeration) numbers, the full advisories were thankfully not exposed, the links to them were broken. (Oh, and the date column shows the dates we got the reports, not the date of the fixed release which is the intention.) We still fear that the names alone plus the CWE descriptions might be enough for intelligent attackers to figure out the rest.

As a direct result of me having revealed information about these three security vulnerabilities, we decided to change the release date of the pending release curl 7.59.0 to happen one week sooner than previously planned. To reduce the time bad actors would be able to abuse this information for malicious purposes.

How exactly did it happen?

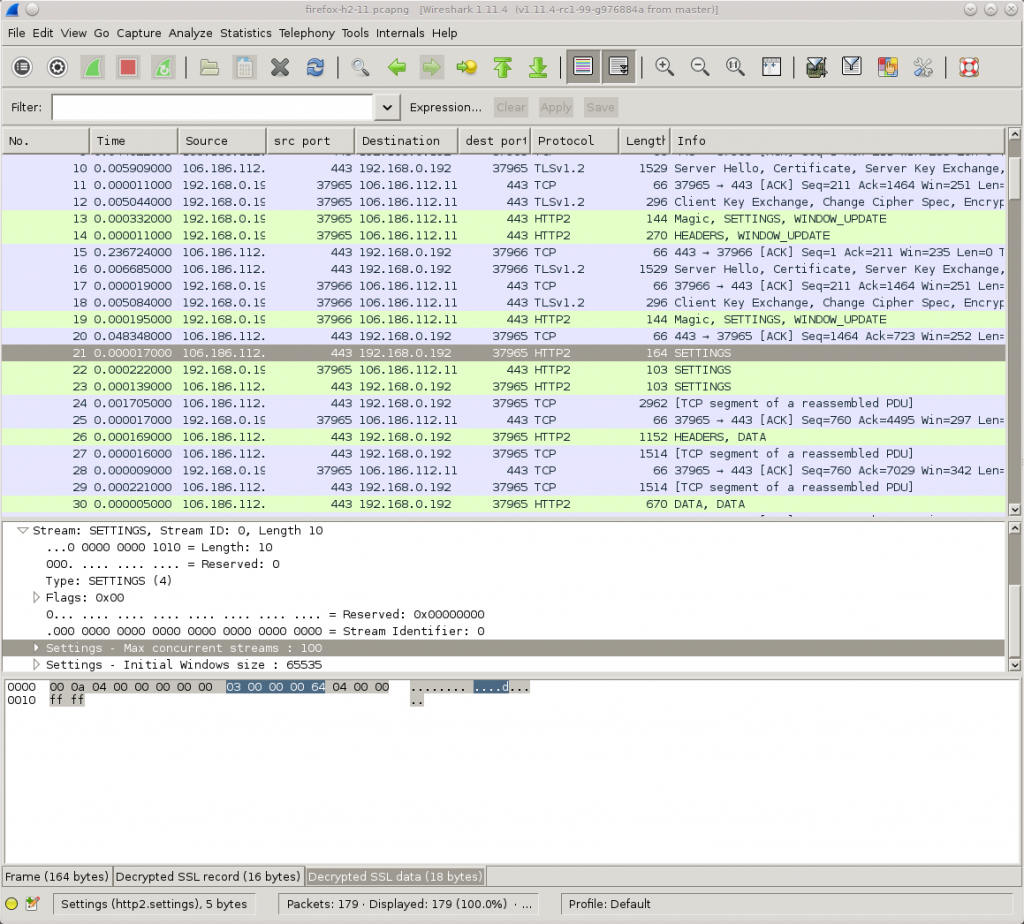

When approaching a release day, I always create local git branches called next-release in both the source and the web site git repositories. In the web site’s next-release branch I add the security advisories we’re working on and I add/update meta-data about these vulnerabilities etc. I prepare things in that branch that should go public on the release moment.

We’ve added CWE numbers to our vulnerabilities for the first time (we are now required to provide them when we ask for CVEs). Figuring out these numbers for the new issues made me think that I should also go back and add relevant CWE numbers to our old vulnerabilities as well and I started to go back to old issues and one by one dig up which numbers to use.

After having worked on that for a while, for some of the issues it is really tricky to figure out which CWE to use, I realized the time was rather late.

– I better get to bed and get some sleep so that I can get some work done tomorrow as well.

Then I realized I had been editing the old advisory documents while still being in the checked out next-release branch. Oops, that was a mistake. I thus wanted to check out the master branch again to push the update from there. git then pointed out that the vuln.pm file couldn’t get moved over because of reasons. (I forget the exact message but it it happened because I had already committed changes to the file in the new branch that weren’t present in the master branch.)

So, as I wanted to get to bed and not fight my tools, I saved the current (edited) file in a different name, checked out the old file version from git again, changed branch and moved the renamed file back to vuln.pm again (without a single thought that this file now contained three lines too many that should only be present in the next-release branch), committed all the edited files and pushed them all to the remote git repository… boom.

You’d think I would…

- know how to use git correctly

- know how to push what to public repos

- not try to do things like this at 01:26 in the morning

curl 7.59.0 and these mentioned security vulnerabilities were made public this morning.