Saturday June 18: I had some curl time in the afternoon and I was just about to go edit the four security advisories I had pending for the next release, to brush up the language and check that they read fine, when it dawned on me.

These particular security advisories were still in draft versions but maybe 90% done. There were details, like dates and links to current in-progress patches, left to update. I also like to reread them a few times, especially in a webpage rendered format, to make sure they are clear and accurate in describing the problem, the solution and all other details, before I consider them ready for publication.

I checked out my local git branch where I expected the advisories to reside. I always work on pending security details in a local branch named security-next-release or something like that. The branch and its commits remain private and undisclosed until everything is ready for publication.

(I primarily use git command lines in terminal windows.)

The latest commits in my git log output did not show the advisories so I did a rebase but git promptly told me there was nothing to rebase! Hm, did I use another branch this time?

It took me a few seconds to realize my mistake. I saw four commits in the git master branch containing my draft advisories and then it hit me: I had accidentally pushed them to origin master and they were publicly accessible!

The secrets I was meant to guard until the release, I had already mostly revealed to the world – for everyone who was looking.

How

In retrospect I can’t remember exactly how the mistake was done, but I clearly committed the CVE documents in the wrong branch when I last worked on them, a little over a week ago. The commit date say June 9.

On June 14, I got a bug report about a problem with curl’s .well-known/security.txt file (RFC 9116) where it was mentioned that our file didn’t have an Expires: keyword in spite of it being required in the spec. So I fixed that oversight and pushed the update to the website.

When doing that push, I did not properly verify exactly what other changes that would be pushed in the same operation, so when I pressed enter there, my security advisories that had accidentally been committed in the wrong branch five days earlier and still were present there were also pushed to the remote origin. Swooosh.

Impact

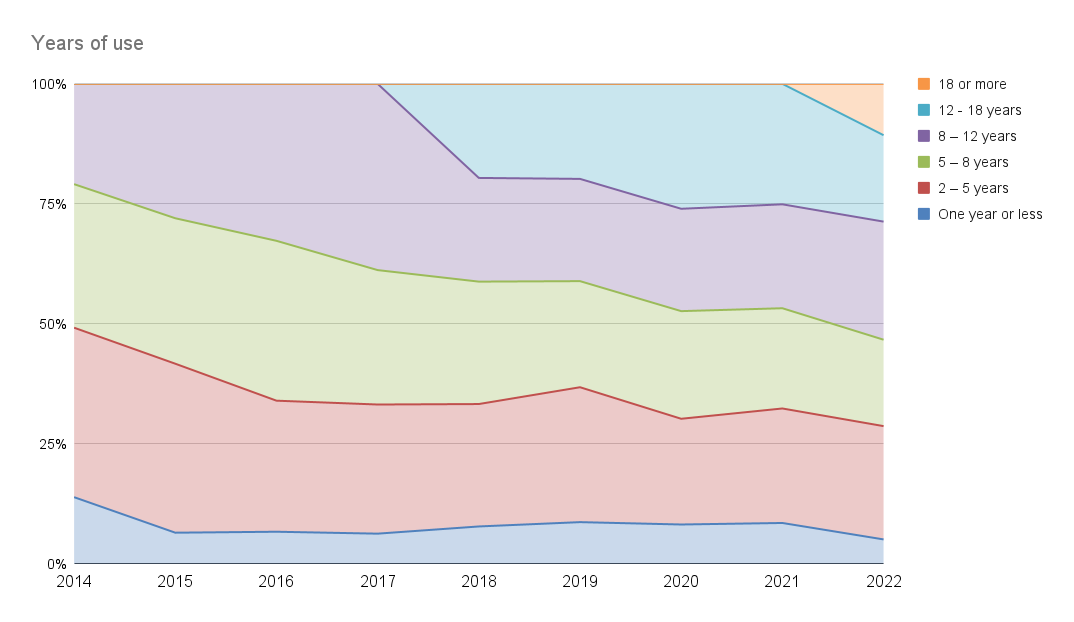

The advisories are created in markdown format, and anyone who would update their curl-www repository after June 14 would then get them into their local repository. Admittedly, there probably are not terribly many people who do that regularly. Anyone could also browse them through the web interface on github. Also probably not something a lot of people do.

These pending advisories would however not appear on the curl website since the build files were not updated to generate the HTML versions. If you could guess the right URL, you could still get the markdown version to show on the site.

Nobody reported this mistake in the four days they were visible before I realized my own mistake (and nobody has reported it since either). I then tried googling the CVE numbers but no search seemed to find and link to the commits. The CVE numbers were registered already so you would mostly get MITRE and other vulnerability database listings that were still entirely without details.

Decision

After some quick deliberations with my curl security team friends, we decided expediting the release was the most sensible thing to do. To reduce the risk that someone takes advantage of this and if they do, we limit the time window before the problems and their fixes become known. For curl users security’s sake.

Previously, the planned release date was set to July 1st – thirteen days away. It had already been adjusted somewhat to not occur on its originally intended release Wednesday to cater for my personal summer plans.

To do a proper release with several security advisories I want at least a few days margin for the distros mailing list to prepare before we go public with everything. There was also the Swedish national midsummer holiday coming up next weekend and I did not feel like ruining my family’s plans and setup for that, so I picked the first weekday after midsummer: June 27th.

While that is just four days earlier than what we had previously planned, I figure those four days might be important and if we imagine that someone finds a way to exploit one of these problems before then, then at least we shorten the attack time window by four days.

curl 7.84.0 was released on June 27th. The four security advisories I had mostly leaked already were published in association with that: CVE-2022-32205, CVE-2022-32206, CVE-2022-32207 and CVE-2022-32208.

Lessons

- When working with my security advisories, I must pay more attention and be more careful with which branch I commit to.

- When pushing commits to the website and I know I have pending security sensitive details locally that have not been revealed yet, I should make it a habit to double-check that what I am about to push is only and nothing but what I expect to be there.

Simultaneously, I have worked using this process for many years now and this is the first time I did this mistake. I do not think we need to be alarmist about it.

Credits

The Swedish midsummer pole image by Patrik Linden from Pixabay. Facepalm photo by Alex E. Proimos.