The IETF QUIC working group had its fifth interim meeting the other day, this time in Kista, Sweden hosted by Ericsson. For me as a Stockholm resident, this was ridiculously convenient. Not entirely coincidentally, this was also the first quic interim I attended in person.

The IETF QUIC working group had its fifth interim meeting the other day, this time in Kista, Sweden hosted by Ericsson. For me as a Stockholm resident, this was ridiculously convenient. Not entirely coincidentally, this was also the first quic interim I attended in person.

We were 30 something persons gathered in a room without windows, with another dozen or so participants joining from remote. This being a meeting in a series, most people already know each other from before so the atmosphere was relaxed and friendly. Lots of the participants have also been involved in other protocol developments and standards before. Many familiar faces.

Schedule

As QUIC is supposed to be done “soon”, the emphasis is now a lot to close issues, postpone some stuff to “QUICv2” and make sure to get decisions on outstanding question marks.

Kazuho did a quick run-through with some info from the interop days prior to the meeting.

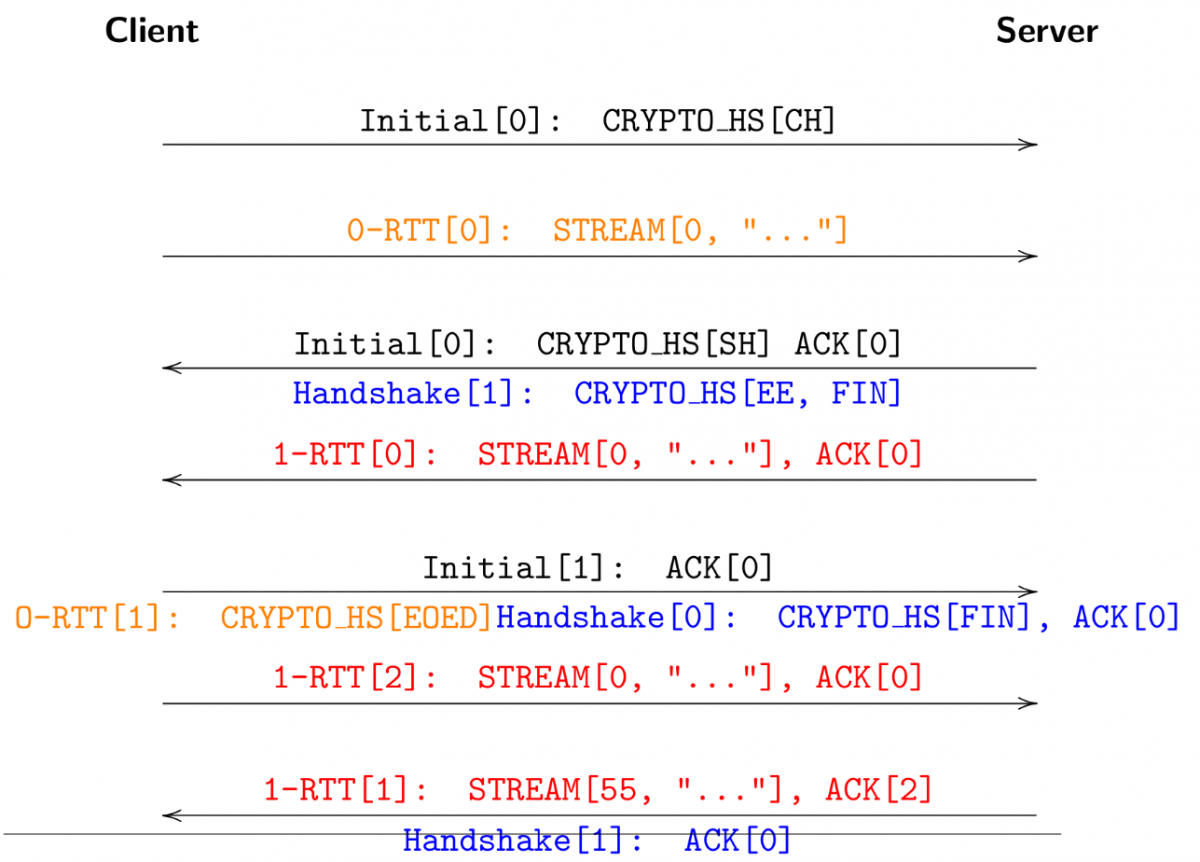

After MT’s initial explanation of where we’re at for the upcoming draft-13, Ian took us a on a deep dive into the Stream 0 Design Team report. This is a pretty radical change of how the wire format of the quic protocol, and how the TLS is being handled.

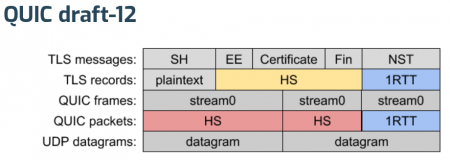

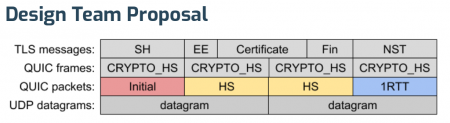

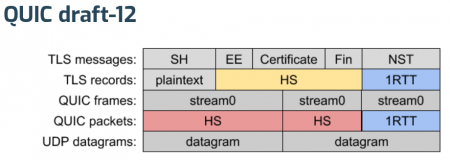

The existing draft-12 approach…

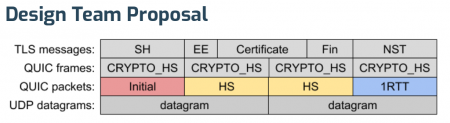

Is suggested to instead become…

What’s perhaps the most interesting take away here is that the new format doesn’t use TLS records anymore – but simplifies a lot of other things. Not using TLS records but still doing TLS means that a QUIC implementation needs to get data from the TLS layer using APIs that existing TLS libraries don’t typically provide. PicoTLS, Minq, BoringSSL. NSS already have or will soon provide the necessary APIs. Slightly behind, OpenSSL should offer it in a nightly build soon but the impression is that it is still a bit away from an actual OpenSSL release.

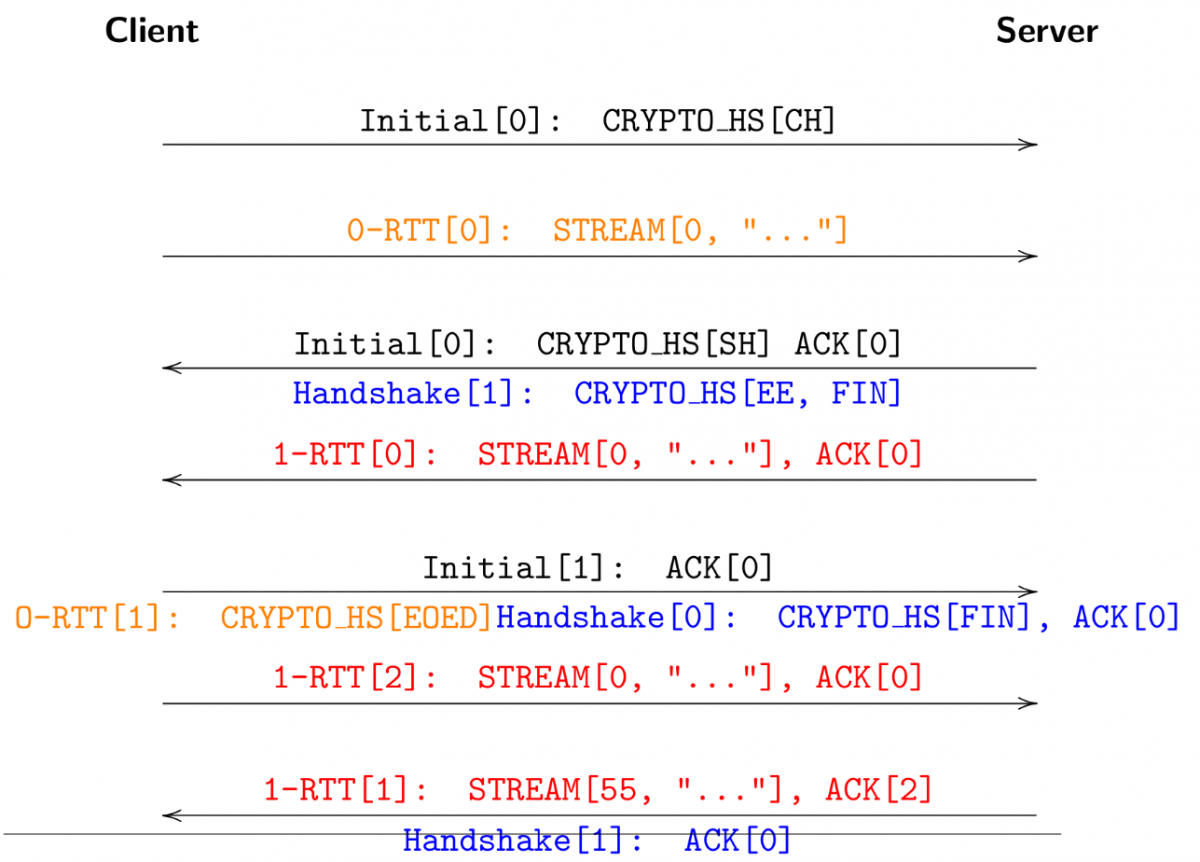

EKR continued the theme. He talked about the quic handshake flow and among other things explained how 0-RTT and early data works. Taken from that context, I consider this slide (shown below) fairly funny because it makes it look far from simple to me. But it shows communication in different layers, and how the acks go, etc.

HTTP

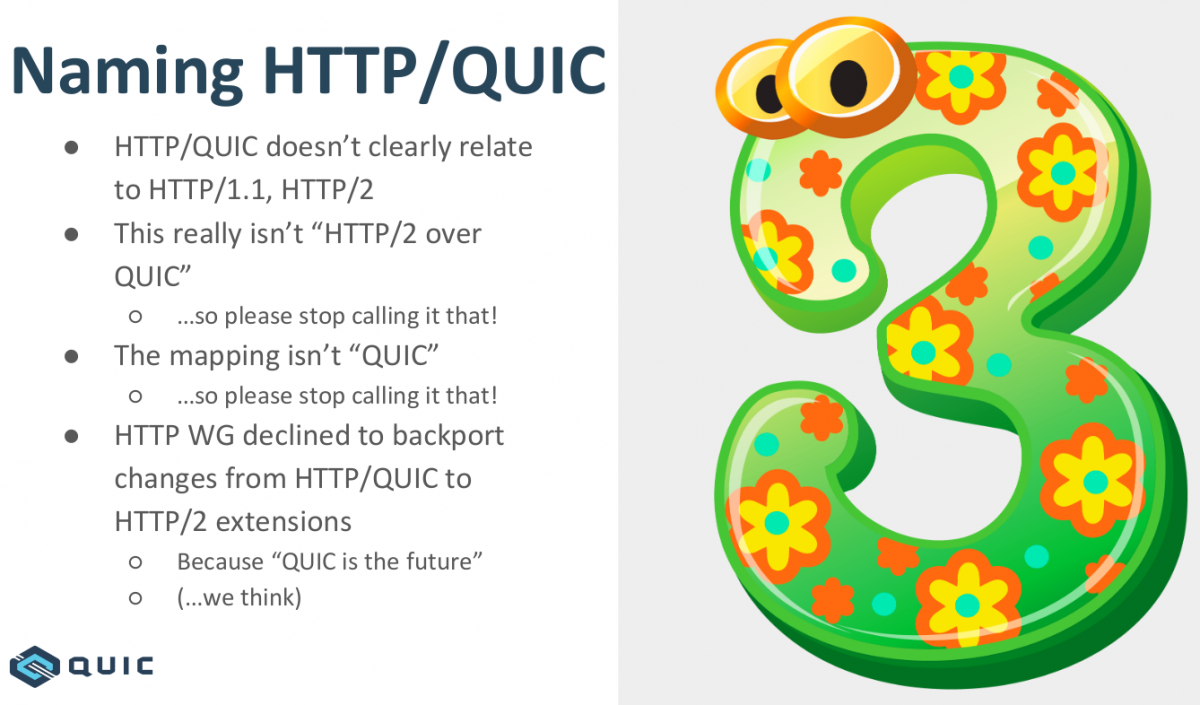

Mike then presented the state of HTTP over quic. The frames are no longer that similar to the HTTP/2 versions. Work is done to ensure that the HTTP layer doesn’t need to refer or “grab” stream IDs from the transport layer.

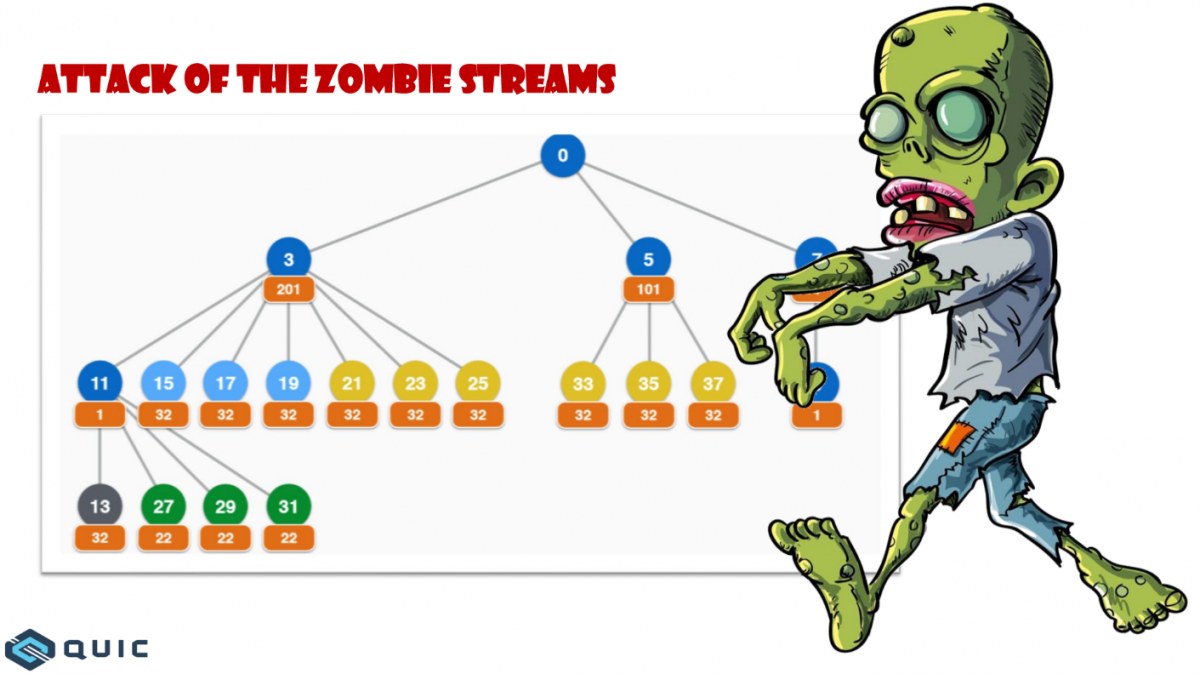

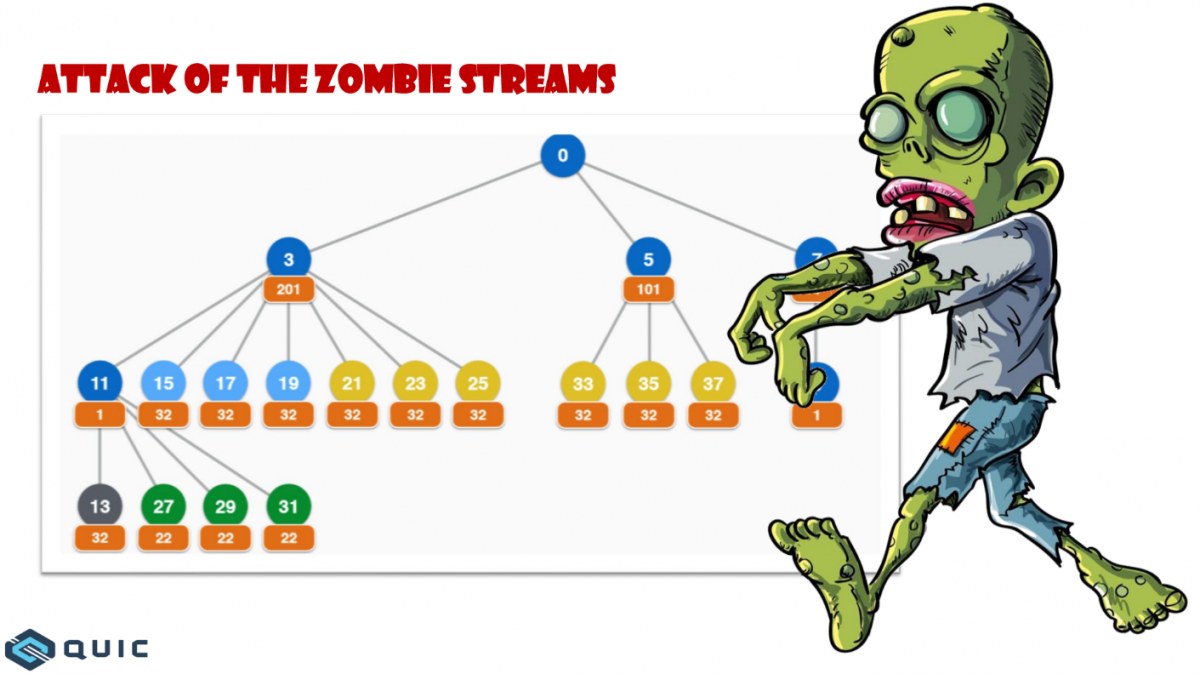

There was a rather lengthy discussion around how to handle “placeholder streams” like the ones Firefox uses over HTTP/2 to create “anchors” on which to make dependencies but are never actually used over the wire. The nature of the quic transport makes those impractical and we talked about what alternatives there are that could still offer similar functionality.

The subject of priorities and dependencies and if the relative complexity of the h2 model should be replaced by something simpler came up (again) but was ultimately pushed aside.

QPACK

Alan presented the state of QPACK, the HTTP header compression algorithm for hq (HTTP over QUIC). It is not wire compatible with HPACK anymore and there have been some recent improvements and clarifications done.

Alan also did a great step-by-step walk-through how QPACK works with adding headers to the dynamic table and how it works with its indices etc. It was very clarifying I thought.

The discussion about the static table for the compression basically ended with us agreeing that we should just agree on a fairly small fixed table without a way to negotiate the table. Mark said he’d try to get some updated header data from some server deployments to get another data set than just the one from WPT (which is from a single browser).

Interop-testing of QPACK implementations can be done by encode + shuffle + decode a HAR file and compare the results with the source data. Just do it – and talk to Alan!

And the first day was over. A fully packed day.

ECN

Magnus started off with some heavy stuff talking Explicit Congestion Notification in QUIC and it how it is intended to work and some remaining issues.

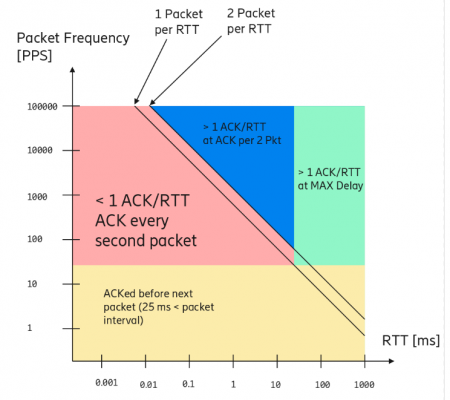

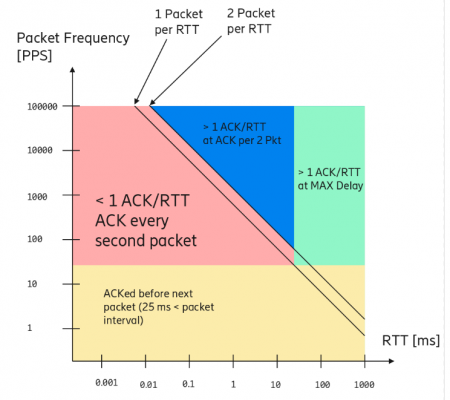

He also got into the subject of ACK frequency and how the current model isn’t ideal in every situation, causing to work like this image below (from Magnus’ slide set):

Interestingly, it turned out that several of the implementers already basically had implemented Magnus’ proposal of changing the max delay to min(RTT/4, 25 ms) independently of each other!

mvfst deployment

Subodh took us on a journey with some great insights from Facebook’s deployment of mvfast internally, their QUIC implementation. Getting some real-life feedback is useful and with over 100 billion requests/day, it seems they did give this a good run.

Since their usage and stack for this is a bit use case specific I’m not sure how relevant or universal their performance numbers are. They showed roughly the same CPU and memory use, with a 70% RPS rate compared to h2 over TLS 1.2.

He also entertained us with some “fun issues” from bugs and debugging sessions they’ve done and learned from. Awesome.

The story highlights the need for more tooling around QUIC to help developers and deployers.

Load balancers

Martin talked about load balancers and servers, and how they could or should communicate to work correctly with routing and connection IDs.

The room didn’t seem overly thrilled about this work and mostly offered other ways to achieve the same results.

Implicit Open

During the last session for the day and the entire meeting, was mt going through a few things that still needed discussion or closure. On stateless reset and the rather big bike shed issue: implicit open. The later being the question if opening a stream with ID N + 1 implicitly also opens the stream with ID N. I believe we ended with a slight preference to the implicit approach and this will be taken to the list for a consensus call.

Frame type extensibility

How should the QUIC protocol allow extensibility? The oldest still open issue in the project can be solved or satisfied in numerous different ways and the discussion waved back and forth for a while, debating various approaches merits and downsides until the group more or less agreed on a fairly simple and straight forward approach where the extensions will announce support for a feature which then may or may involve one or more new frame types (to be in a registry).

We proceeded to discuss other issues all until “closing time”, which was set to be 16:00 today. This was just two days of pushing forward but still it felt quite intense and my personal impression is that there were a lot of good progress made here that took the protocol a good step forward.

The facilities were lovely and Ericsson was a great host for us. The Thursday afternoon cakes were great! Thank you!

Coming up

There’s an IETF meeting in Montreal in July and there’s a planned next QUIC interim probably in New York in September.

It’s been five great years, but now it is time for me to move on and try something else.

It’s been five great years, but now it is time for me to move on and try something else. I had already before I joined the Firefox development understood some of the challenges of making a browser in the modern era, but that understanding has now been properly enriched with lots of hands-on and code-digging in sometimes decades-old messy C++, a spaghetti armada of threads and the wild wild west of users on the Internet.

I had already before I joined the Firefox development understood some of the challenges of making a browser in the modern era, but that understanding has now been properly enriched with lots of hands-on and code-digging in sometimes decades-old messy C++, a spaghetti armada of threads and the wild wild west of users on the Internet. I had worked on curl for a very long time already before joining Mozilla and I expect to keep doing curl and other open source things even going forward. I don’t think my choice of future employer should have to affect that negatively too much, except of course in periods.

I had worked on curl for a very long time already before joining Mozilla and I expect to keep doing curl and other open source things even going forward. I don’t think my choice of future employer should have to affect that negatively too much, except of course in periods. I was involved in the IETF HTTPbis working group for many years before I joined Mozilla (for over ten years now!) and I hope to be involved for many years still. I still have a lot of things I want to do with curl and to keep curl the champion of its class I need to stay on top of the game.

I was involved in the IETF HTTPbis working group for many years before I joined Mozilla (for over ten years now!) and I hope to be involved for many years still. I still have a lot of things I want to do with curl and to keep curl the champion of its class I need to stay on top of the game.

The

The